Quick and aggressive responses to multiple complications have led to remarkable recovery

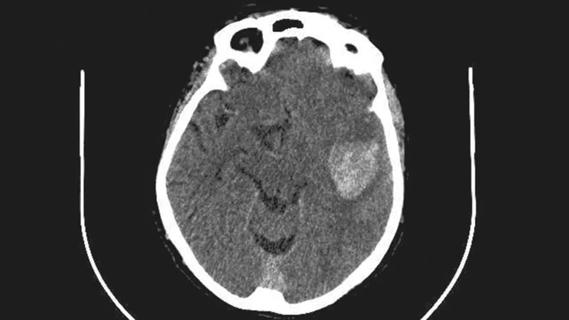

A 38-year-old previously healthy woman lost consciousness at home, and her young daughter immediately called for help. When she briefly came to, her speech was slurred and she complained of head pain. By the time emergency medical services arrived, she was comatose. She was rushed by ambulance to nearby Cleveland Clinic Hillcrest Hospital, where she was intubated and underwent a CT scan, which showed subarachnoid hemorrhage (Figure 1).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/7813353a-d898-4aeb-9334-e63164ea917f/Brain-aneurysm-case-study-inset1)

Figure 1. Initial head CT scan showing extensive subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Because the findings indicated advanced neurological care was needed, she was quickly life-flighted by helicopter to Cleveland Clinic’s main campus. “The patient arrived in extremis,” says Cleveland Clinic neurosurgeon Nina Moore, MD, who admitted her to the cerebrovascular neurosurgery service. “In such cases, we quickly convene a team of neurological specialists to develop a strategy.”

The patient was immediately sent to the operating room, where Dr. Moore emergently placed a drain to alleviate the high intracranial pressure. Cerebral angiography was then performed (Figure 2) to search for a source of the bleed.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/538f1cde-6497-43cd-a3f3-c55d768a85cc/Brain-aneurysm-case-study-inset2)

Figure 2. Angiogram showing aneurysm of the right anterior cerebral artery (at center of image) with irregular “bubbles” visible.

Interventional neurologist M. Shazam Hussain, MD, Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Cerebrovascular Center, promptly performed endovascular coiling. Repeat angiography indicated that the aneurysm was filled (Figure 3).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/af93cbb0-9856-490c-b0e9-9fe4f66fff98/Brain-aneurysm-case-study-inset3)

Figure 3. Angiogram of the aneurysm post-coiling.

Grade 5 aneurysm, the most severe grade in the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) classification, is defined as being associated with a Glascow Coma Scale score of 3 to 6. It has a 90% fatality rate even with prompt intervention, and survivors are usually left with neurological sequelae.

“These patients must be watched extremely closely and treated aggressively,” says neurocritical care specialist Adam Barron, MD, who was involved with the patient’s initial assessment and led her neurology critical care team.

The patient was kept sedated and given medications to try to reduce brain edema. Dr. Barron stayed in close contact with Dr. Moore and, as pressures worsened, they decided to place a second drain. Despite this, pressures continued to rise, and Dr. Moore next performed a hemicraniectomy.

Advertisement

“The edema seen on CT (Figure 4), despite the presence of two drains and removal of a large piece of skull, was about the worst I’ve ever seen in a patient who ultimately survived,” says Dr. Moore.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/388705b5-37fb-494b-b7c0-d97ff71720d0/Brain-aneurysm-case-study-inset4)

Figure 4. CT revealing severe swelling of brain tissue after hemicraniectomy and insertion of a second drainage tube.

The patient stabilized, and although she was still in an induced coma, she had encouraging signs of intact brain function, such as the ability to squeeze her hand on command. However, daily transcranial Doppler ultrasonography revealed that vasospasm was developing, and medications were given to try to address it. Ultrasound and clinical indicators worsened, and on hospital day 4, she was taken in for angioplasty.

Vasospasm, commonly occurring from 3 to 14 days after a subarachnoid hemorrhage, must be treated to prevent a stroke and further neurological deficit. However, Cleveland Clinic interventional neurologist Gabor Toth, MD, explains that every action in such a situation poses a dilemma that requires balancing the need to restore blood flow with the imperative to avoid rupturing the vessel.

“We needed every tool in our toolbox to treat this case,” says Dr. Toth. “As the patient’s condition was so dire, we had to be very aggressive.”

When medications delivered directly to the brain failed to relax the vessel, Dr. Toth performed endovascular balloon dilation. When that also proved inadequate, he deployed a retractable stent-like device, which successfully restored blood flow.

Dr. Barron started to slowly wean the patient from medications and allow her to fully regain consciousness. She was extubated on hospital day 9, after which she was soon interacting with family members and her medical team. A speech deficit was evident, as was left-sided weakness.

Advertisement

Physical, occupational and speech therapy programs were started. Drains were removed, and at one month, her bone flap was reattached. Three weeks after admission, she was discharged to a Cleveland Clinic inpatient rehabilitation facility. She returned home two weeks later and continued with outpatient therapy.

“Considering the gravity of her situation, we were all amazed that she survived and how quickly her recovery progressed,” Dr. Moore says. The team credits her favorable outcome to the following:

Advertisement

Ten months after her ruptured aneurysm, the patient can walk freely without assistance and is able to drive her daughters to their activities and enjoy cooking and travel again. She is still working on improving speech, and she will continue to be followed with imaging of the aneurysm to monitor for leakage or growth. Family members were informed of their need to manage risk factors.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Evolving thinking on when and how to treat brain aneurysms and AVMs

Results may refine surgical selection criteria and advance clinical trial design

Case series links catastrophic outcomes to therapy initiation within 48 hours post-procedure

Scientific program chair reflects on what may resonate longest from this year’s neurosurgery conference

ENRICH trial marks a likely new era in ICH management

Digital subtraction angiography remains central to assessment of ‘benign’ PMSAH

Cleveland Clinic findings prompt efforts for broad data pooling

Case series demonstrates successful retreatment of this rare emergency