Schwannoma of the lacrimal nerve threatened right eye blindness

A 65-year-old woman presented to Cleveland Clinic ophthalmologist Gregory Kosmorsky, DO, with progressive vision loss in the right eye. An outside provider had previously performed cataract surgery on the right eye, without improvement.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

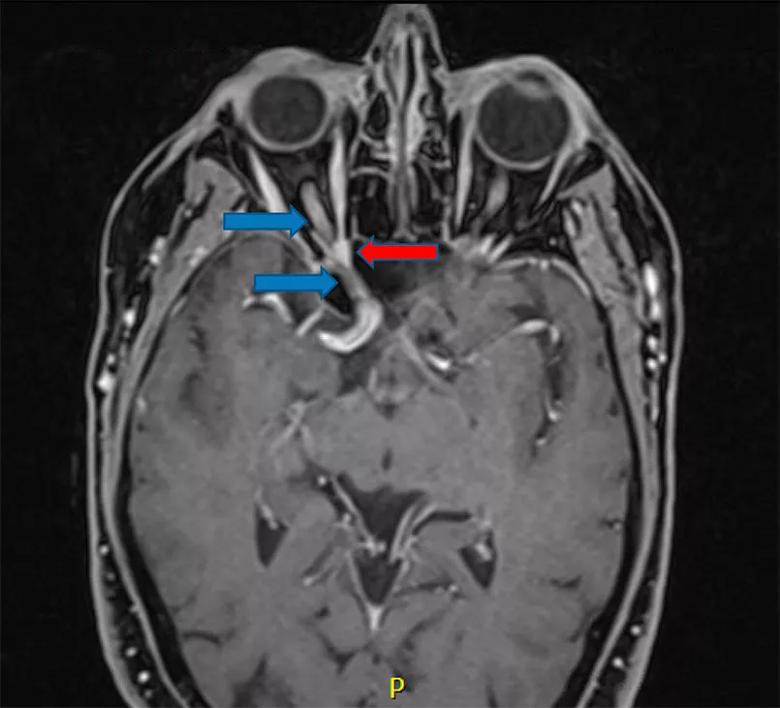

Dr. Kosmorsky, staff in the Department of Neuro-Ophthalmology, suspected a cause other than cataracts and ordered an MRI of the head, which revealed a schwannoma of the lacrimal nerve in the suborbital apex of the optic canal, medial to the optic nerve. The tumor was compressing the optic nerve, which was believed to explain the vision loss (Figures 1 and 2).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2ec863ef-1efb-4f7e-9933-b2b9d79d7ad7/21-NEU-2051980-Inset-1_Schwannoma-of-lacrimal-nerve_jpg)

Figure 1. Preoperative axial MRI (T1 with contrast, fat suppressed) demonstrating the right optic nerve (blue arrows) with significant compression at the orbital apex by a small schwannoma (red arrow) arising from the lacrimal nerve. Although the tumor was small (7 mm), the orbital apex and optic canal are narrowest in this area, which means even a small tumor can cause significant compression on the optic nerve, resulting in progressive vision loss.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/72c79c89-13db-44ef-9070-c93b34afc56e/21-NEU-2051980-Inset-2_Schwannoma-of-lacrimal-nerve_jpg)

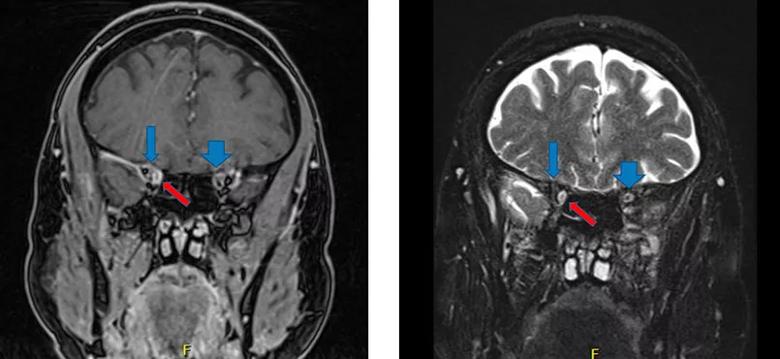

Figure 2. Preoperative coronal MRIs (T1 with contrast, fast suppressed, on left; T2 on right) demonstrating the right optic nerve (blue arrows) being displaced superiorly and laterally by the lacrimal nerve schwannoma (red arrow). Note how different the position of the right optic nerve is compared with the left (blue arrowheads).

Although typically benign, schwannomas in the orbit are rare and difficult to manage, particularly in the narrow setting of the optic canal. From an ophthalmological standpoint, surgically accessing the tumor through the eye would further compress the optic nerve, potentially risking full loss of vision in the eye. Whereas radiation therapy can be used in an effort to slow tumor growth, it cannot remove the tumor and carries its own risks to the eye.

Advertisement

Dr. Kosmorsky was aware that a multidisciplinary Cleveland Clinic surgery team had had success removing similar tumors via endonasal access. Given that the medial location of the patient’s tumor favored an endonasal approach, he referred the patient to the skull base surgery team of neurosurgeon Pablo Recinos, MD, and rhinologist Raj Sindwani, MD.

The two-surgeon team accessed the tumor through the nose by opening the adjacent ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses to develop a nasal corridor allowing for a direct-line approach to the orbital apex, where the tumor was located. Creating adequate space at the back of the nose by resecting a small amount of the posterior septum permitted the team to work using multiple instruments passing simultaneously though both nostrils.

“This multi-handed approach is key to being able to safely dissect, reflect and retract structures within the orbit so that the tumor is delicately removed without injuring the critical nearby anatomy,” Dr. Sindwani explains.

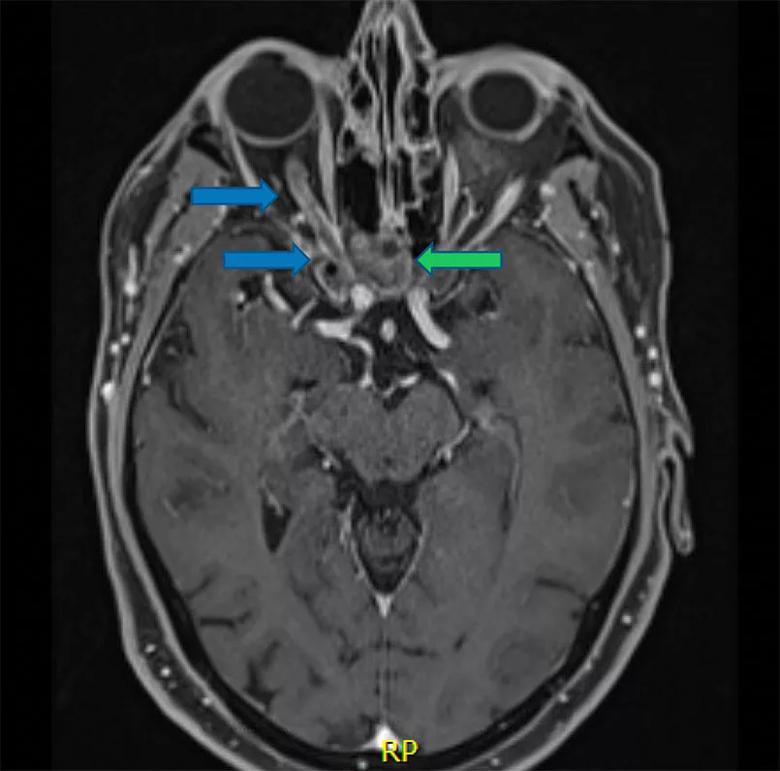

Using neuronavigation guidance based on the patient’s MRI and CT findings, the surgeons pinpointed the location to open and allow direct access to the tumor in the orbital apex. After decompressing the bone covering the optic nerve and posterior orbit, they incised the periorbita of the posterior orbit and began to peel off the tumor without putting pressure on the nerve. Complete tumor resection was achieved and the optic nerve was restored to its normal position (Figure 3).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e280472c-19a2-4421-9eb9-9f3f0713a137/21-NEU-2051980-Inset-3_Schwannoma-of-lacrimal-nerve_jpg)

Figure 3. Postoperative axial MRI (T1 with contrast, fat suppressed) demonstrating complete removal of the tumor with the right optic nerve (blue arrows) in normal position and the absorbable packing material (green arrow) left in the sphenoid sinus, which served as the corridor for removing the tumor.

Advertisement

“Generally, not much reconstruction is required after this minimally invasive approach,” Dr. Sindwani notes, “as this area of the body is great at healing itself.” After a straightforward closure involving simple placement of a small amount of absorbable dressing directly against the surgical site at the back of the eye, the patient had an uneventful overnight stay and was discharged the next day. “No uncomfortable packing material or splints were necessary, and there were no cuts or bruises on the patient’s face,” Dr. Sindwani remarks.

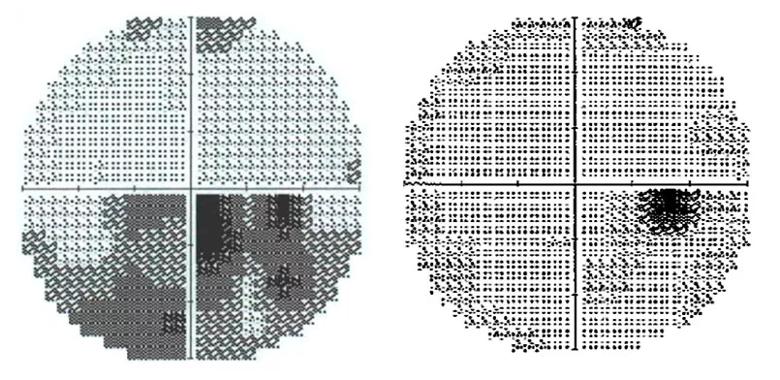

She noted significantly improved vision, which was confirmed when her postoperative visual field testing was found to be restored to near normal (Figure 4).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4b5b4c85-5485-4734-b320-df49c2af7cc3/21-NEU-2051980-Inset-4_Schwannoma-of-lacrimal-nerve_jpg)

Figure 4. Left: Preoperative visual field study of the right eye demonstrating significant visual field deficits, particularly in the inferior nasal and temporal fields. Right: Postoperative visual field study demonstrating complete resolution of the preoperative deficits, with the only dark area not seen corresponding to an expected blind spot from the retina.

“For a tumor or any pathology that’s pressing on a nerve, the longer and the greater the compression, the more severe the neurological or functional deficit, and the lower the likelihood of restoration to previous function,” says Dr. Recinos, Section Head of Skull Base Surgery in Cleveland Clinic’s Rose Ella Burkhardt Brain Tumor and Neuro-Oncology Center. “Even though this patient’s schwannoma wasn’t large, its location compressing the optic nerve meant that she faced likely progression to blindness in her right eye without tumor removal.”

Advertisement

Prior to the development of the endonasal approach used in this case, patients with a tumor in proximity to the optic nerve had very limited options to avoid vision loss. Even now, many patients aren’t offered the endonasal surgery option because only a handful of U.S. centers provide it, and familiarity with the option is not widespread among ophthalmologists and other referring physicians.

“A tumor in this location occupies a no-man’s-land that straddles specialties,” Dr. Recinos observes. “Neurosurgeons will typically say, ‘This is in the eye; that’s not my area.’ Otolaryngologists and even rhinologists will typically say, ‘I don’t do surgeries in the eye.’ Ophthalmic and oculoplastic surgeons will say, ‘It’s not safe to operate way back there.’ As a result, many patients are told that nothing can be done for them.”

Drs. Recinos and Sindwani and a few other colleagues on Cleveland Clinic’s endoscopic skull base team remove challenging orbital tumors such as tuberculum sellae meningiomas on a consistent basis, typically doing about 10 to 15 cases a year. Intraorbital tumors like the one in this case are rarer. “We’ve done about six or seven cases like this where the tumor is deep within the orbit, sometimes even located entirely within the intraconal space,” Dr. Recinos says. In all cases, progression of vision loss was halted; in all but one case, vision improved significantly postoperatively.

The surgical principles in cases involving the eye are similar to those for other orbital tumors, the surgeons say. A key ingredient is experience of the surgical team, particularly in terms of extensive collaboration between the neurosurgeon and rhinologist. “The operation in these cases is like a partner dance,” says Dr. Recinos. “It can’t be done by one person alone.”

Advertisement

The rhinologic surgeon brings the requisite sinus surgery expertise, from creation of a safe corridor for operative maneuvering to optimal reconstruction, drawing on tissues from various sites within and outside the nose. Dr. Sindwani also brings distinctive expertise in orbital surgery, which he shares in a recently published textbook on endoscopic approaches to the orbit that catalogs the utility of these innovative surgical techniques and provides expert guidance on when and how to perform them.

“The endoscopic endonasal approach to orbital tumors offers the benefits of improved visualization, a straight-line trajectory, and less disruption or retraction of normal orbital structures, including the sensitive optic nerve,” Dr. Sindwani says. “In our experience, this means better outcomes, less morbidity and a faster recovery.”

The neurosurgeon brings expertise in intracranial and transcranial surgery, including experience in orbital tumors and intimate familiarity with the tiny vessels that feed the optic nerves. “Neurosurgeons frequently treat orbital tumors from above, with a cranial approach, although some of us have expertise treating through the nose, which is one of my specialty interests,” says Dr. Recinos.

Beyond the dual expertise, these cases require that the two surgeons have real comfort working together on the same problem. “At the most critical part of the procedure, there are two hands manipulating instruments through the nostril at the same time, with a third hand guiding the endoscopic camera for visualization and sometimes a fourth hand if suction or irrigation is needed,” Dr. Sindwani notes.

Both surgeons stress that the need for close coordination cannot be overstated. “It’s invaluable to have the deep experience we have working with each other,” says Dr. Recinos.

While patients can be hesitant to consider invasive surgery of this type for a nonmalignant tumor, particularly if their vision loss is still relatively mild, the surgeons say that early intervention can be key. “I tell patients the primary goal is to stop their vision from getting worse,” says Dr. Recinos. “The secondary goal is for their vision to get better. There’s no question that removing the tumor can restore lost vision, but the chances and degree of restoration are greater the sooner we remove the tumor.”

For that reason, the surgeons’ advice to ophthalmologists and other referring providers is to be aware of this endonasal option and consider a consultation for tumors that are inoperable through the eye, particularly if the location is medial to the optic nerve. “Before telling a patient there are no options, consult with a surgical team that has experience with these operations,” concludes Dr. Recinos. “And sooner is better. The aim is to minimize the period during which vision loss progresses.”

Advertisement

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges