Case study underscores the imperative for thorough evaluation with SEEG

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Periventricular nodular heterotopia (PVNH) is a malformation of cortical development marked by masses of neurons and glial cells near the periventricular germinal matrix. PVNH frequently has intrinsic epileptogenicity but is not always a primary contributor to the epileptogenic zone. Each patient with PVNH has his or her own specific epileptogenic network that can include the heterotopic nodule, the overlying cortex or both. Analysis of these complex networks often requires stereoelectroencephalography (SEEG) for detailed assessment of various distinct neurophysiologic signatures that may help guide epilepsy surgical strategies.

Some patients with PVNH, despite their complexity, can have successful epilepsy outcomes with minimally invasive procedures, as illustrated in the case study below.

A 28-year-old left-handed man presented to Cleveland Clinic’s epilepsy clinic with seizures that had started six years previously. The first was a tonic-clonic seizure that occurred in the context of sleep deprivation. Although he had only four more tonic-clonic seizures since then, he later developed focal seizures that occurred in clusters of three to eight per day. These clusters were happening about three times a month.

The focal seizures often were preceded by an aura that he described as “entering into a dream with things fading away.” During the aura, sounds seemed louder, particularly his own voice. He might involuntarily grin or laugh and say sentences in which the words were clear but the content of his speech was out of context. He would then develop a blank stare and typically stretch his right arm across his chest, have fumbling movements of his left hand or elevate both arms.

Advertisement

He was unable to drive because of his seizures, and they negatively affected his job as a salesman. A series of antiseizure medication trials had failed to achieve seizure control. He was currently taking oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine and levetiracetam.

The patient underwent a series of noninvasive tests:

In summary, initial testing supported focal epilepsy likely arising from the right temporoparietal region in the nondominant hemisphere. It was uncertain whether epileptogenicity involved PVNH, overlying cortex and/or the hippocampal formation.

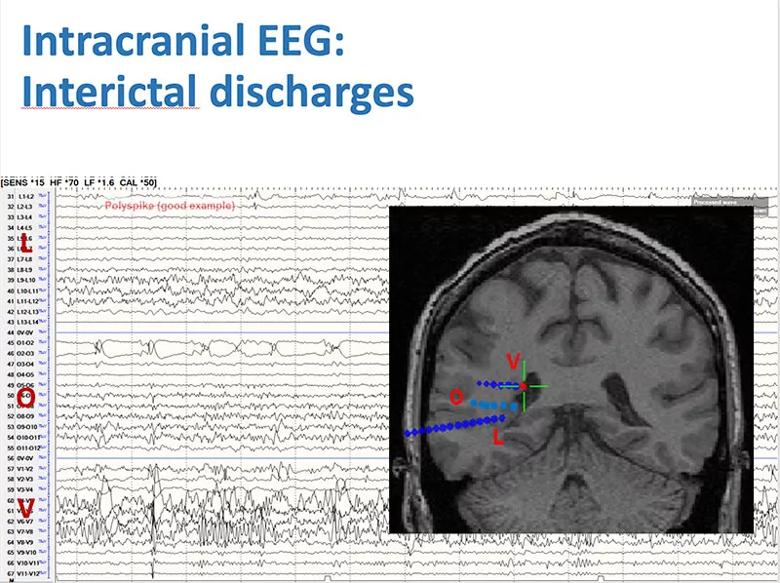

SEEG evaluation was undertaken to better characterize the source of seizure activity. Frequent small-amplitude spikes, usually in long runs and at times synchronized, were seen in all three heterotopic nodules, as were sequences of low-voltage fast activity. Several seizures started within heterotopic nodules and almost simultaneously showed clear evolution of low-voltage fast activity with the contacts in nearby white matter (Figure 1).

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e3024197-c048-4f95-8d9d-34fc9a1e71e5/22-NEU-2918752-CQD-Inset1-800x598-1_jpg)

Figure 1

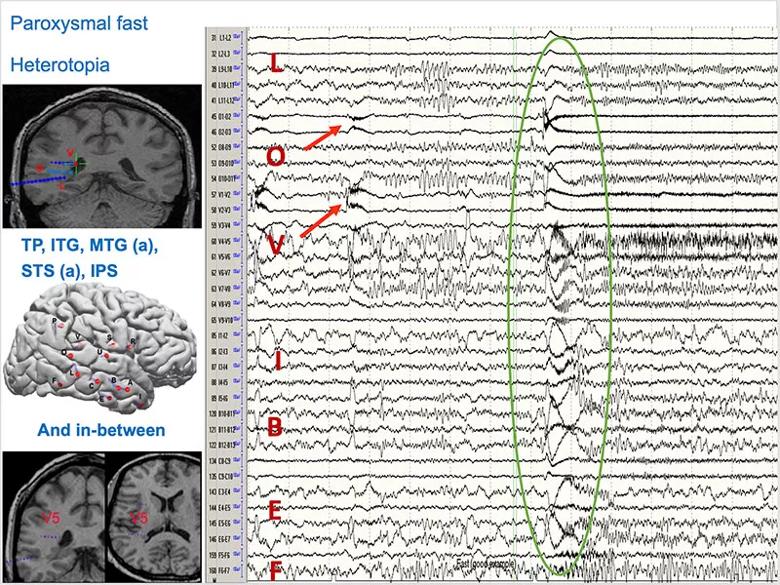

Occasional spikes were seen in the amygdala and hippocampus, with a little more frequency as the seizure progressed (Figure 2).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/39f5e884-3d0a-471d-a8c7-b6019702a200/22-NEU-2918752-CQD-Inset2-800x600-1_jpg)

Figure 2

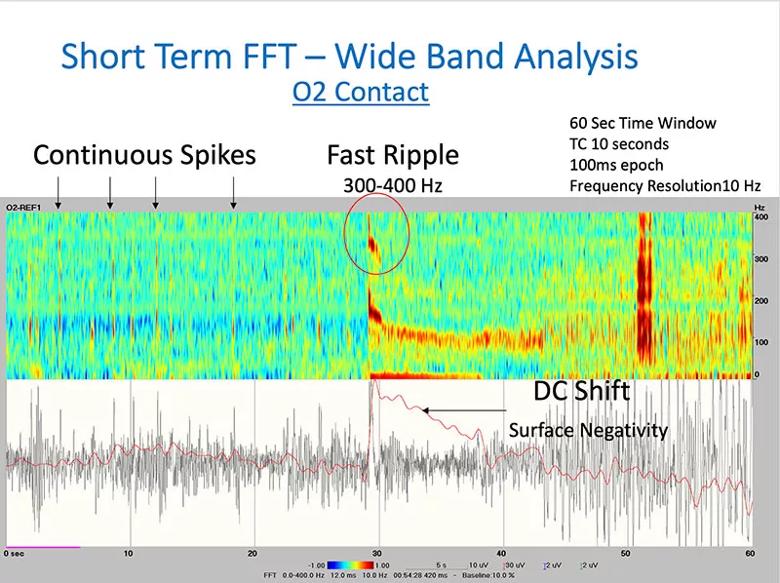

Short-term Fourier transformation wide band analysis of one of the two O electrodes revealed a DC shift (Figure 3), a physiological marker that can be helpful in understanding the epileptogenic zone.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/060757e1-c265-4d2a-8219-e7e58ec6adbb/22-NEU-2918752-CQD-Inset3-800x598-1_jpg)

Figure 3

Fingerprint analysis uses time-frequency plots of each contact pair at the pre-ictal to ictal transition, showing the combination of features of preictal spikes, multiband fast activity and suppression of slower background frequencies. The classifier identified the contact pairs (L1-L2, V-V2 and O1-O2) in the heterotopic nodules as showing features consistent with the epileptogenic zone, whereas those in the micronodule and cortex did not.

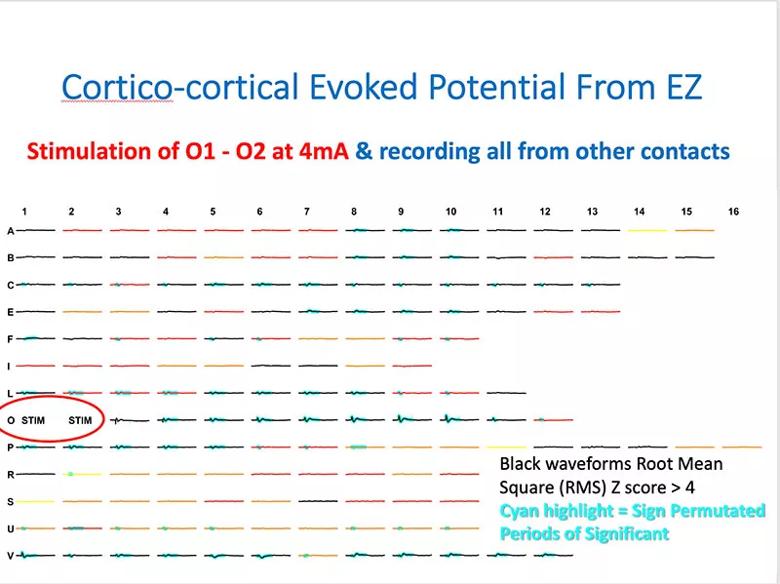

Cortico-cortical evoked potentials (CCEP) can reveal connectivity within brain networks and is used to study the propagation networks from stimulating within the ictal onset zone. It showed extensive connectivity of heterotopic nodules with the overlying cortex and adjacent cortices consistent with the ictal propagation network noted on SEEG (Figure 4). Stimulation at L1-L2 produced the patient’s characteristic aura.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/080676d7-8640-4127-9a1d-aee8e652d459/22-NEU-2918752-CQD-Inset4-800x599-1_jpg)

Figure 4

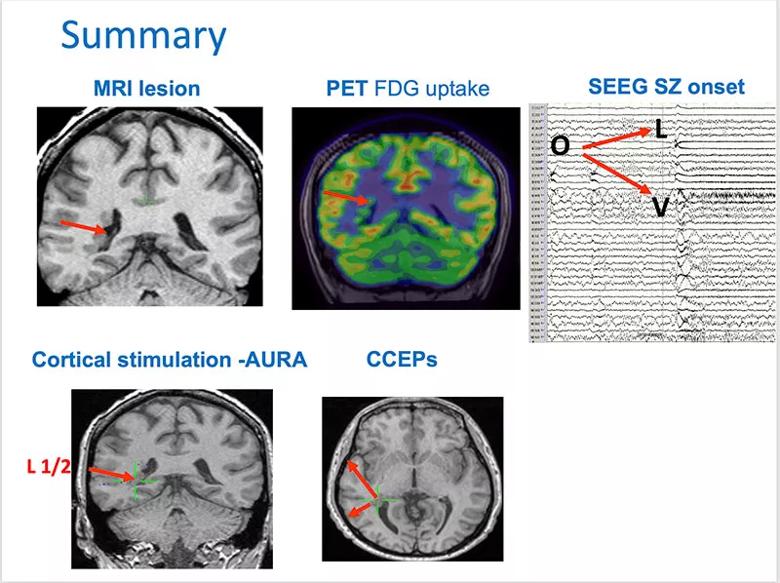

Discussion of the case at a multidisciplinary patient management conference identified much concordance between findings from MRI, FDG-PET uptake, and SEEG and advanced testing (Figure 5). Evidence supported the hypothesis that the epileptogenic zone arose from the heterotopic nodules and resulted in frequent interictal discharges, ictal onset of typical seizures, cortical stimulation inducing the typical auras, and connectivity (i.e., ictal propagation) to the overlying cortex.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c98baccf-e3f7-4242-8ece-a33567239270/22-NEU-2918752-CQD-Inset5-800x598-1_jpg)

Figure 5

Epileptogenicity was also evident in the vicinity of the nodules, with micronodules in the adjacent white matter. Quick synchronization occurred with the lateral temporal neocortex, extending to the temporal pole, apparently triggered by epileptogenicity from the nodules.

Multiple treatment options were considered. Nodular surgery is difficult, especially with the overlying white matter in potentially eloquent areas. The approach — either from the surface down or the other way — can be difficult. Entering the ventricle should be avoided, as it involves risk of complications. Going through the ventricle with an endoscope and resecting the nodule is a possibility, but is limited for lateral resection. Many of these issues are moot with a larger neocortical resection, but there was little to suggest that the overlying cortex needed to be removed.

Each of various options for addressing the nodules — laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation or Gamma Knife™ stereotactic radiosurgery —has advantages and disadvantages. Laser ablation has the advantage of guidance from the heat created with the MRI scan in real time. However, it is difficult to ablate a lesion next to a fluid-filled space, as the heat preferentially flows into fluid.

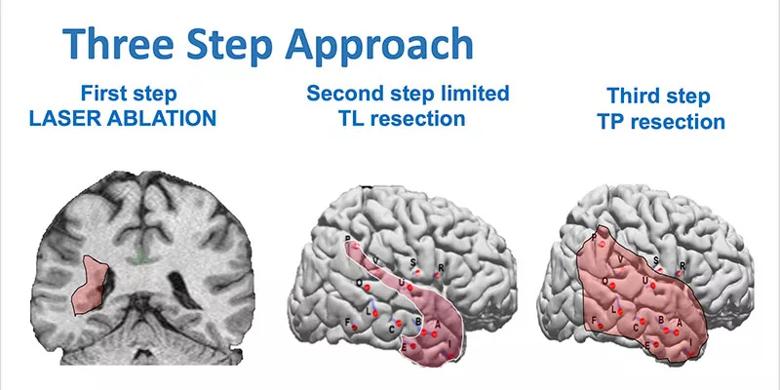

After considerable discussion, a three-step approach was agreed upon (Figure 6), with continuation to subsequent steps only if required:

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/24914269-5b82-4ad0-af10-c15e4b7e1fe0/22-NEU-2918752-CQD-Inset6-800x400-1_jpg)

Figure 6

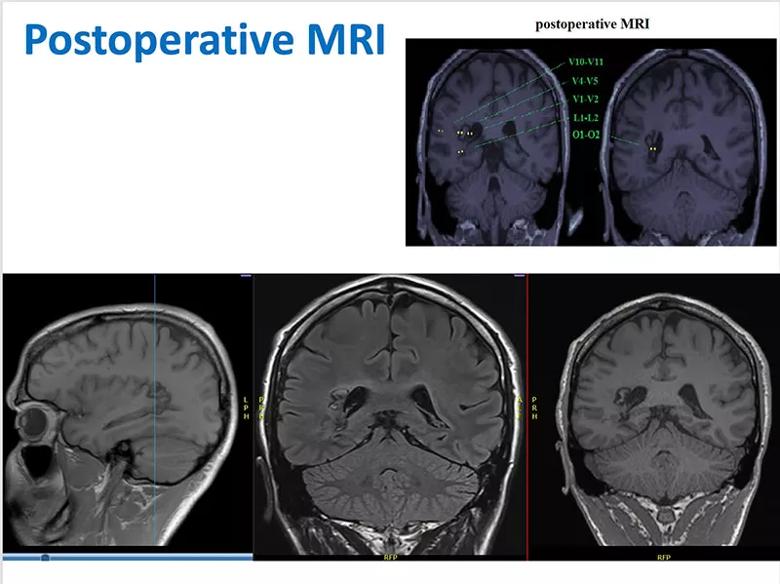

The nodules were ablated using laser ablation (Figure 7). A bit of residual nodule remained apparent at the L1 electrode, although the lateral connection between the nodule and white matter appeared successfully ablated.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a617df6c-ff23-4113-8229-043d601c34a1/22-NEU-2918752-CQD-Inset7-800x601-1_jpg)

Figure 7

Four years after the initial laser ablation, the patient is doing well and is gainfully employed. He has no neurological deficits and is free of seizures and auras. He is off oxcarbazepine and continues on a reduced dose of lamotrigine 200 mg twice daily and levetiracetam XR 3,000 mg at bedtime.

Dr. Nair is Section Head of Adult Epilepsy and Director of Intraoperative Neurophysiologic Monitoring at Cleveland Clinic. Additional details of this case are described in Epilepsy & Behavior Case Reports (2019;11:4-9).

Advertisement

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges