Diagnosis and treatment of rotational vertebrobasilar insufficiency syndrome

A 77-year-old man was admitted to a Cleveland Clinic hospital after a fall. He reported a yearlong history of difficulty walking, intermittent vertigo, syncope and longstanding headache. He also noted veering to the left when he walked. These symptoms appeared only when he moved his head in a particular way.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Prior to admission, he had seen providers at other institutions with no answers. A neutral angiogram showed a complete occlusion in his right vertebral artery. The patient was referred to interventional neurologist Shazam Hussain, MD, Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Cerebrovascular Center.

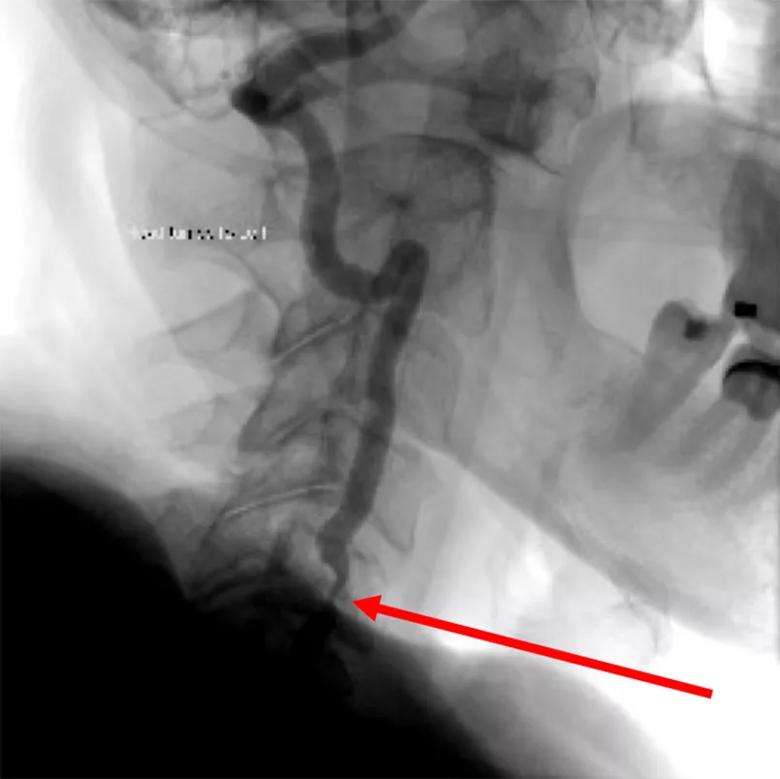

While the occluded vertebral artery was significant, it didn’t explain the patient’s symptoms. Dr. Hussain noticed on the angiogram an indentation, perhaps from a bone spur, in the left vertebral artery. He ordered a dynamic angiogram and was able to verify that, when the patient twisted his neck, the left vertebral artery also became almost completely occluded, thus blocking all blood supply to the cerebellum (Figure 1). Dr. Hussain diagnosed the patient with rotational vertebrobasilar insufficiency syndrome, or bow hunter’s syndrome, and referred him to Ajit Krishnaney, MD, a neurosurgeon in the Center for Spine Health.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5e6f1240-82e2-422d-b16a-c09818625ef2/20-NEU-1875736_CQD_1_inset-805x804-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Angiogram showing severe vertebral artery stenosis (arrow) upon turning of the head to the left.

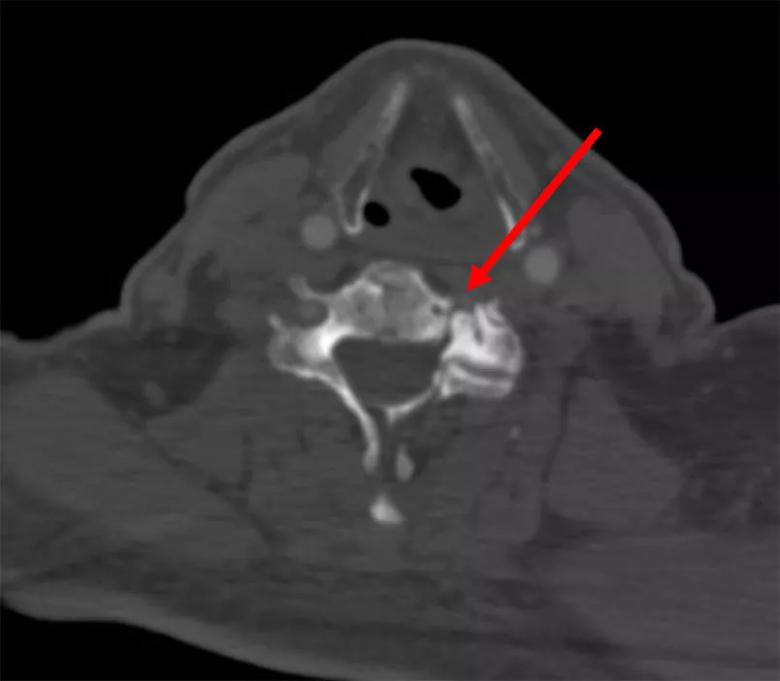

The superior articulating process appeared to jut into and compress the vertebral artery when the patient moved his head (Figure 2). Thus, with a posterior approach, Dr. Krishnaney deconstructed the C5-6 joint and drilled the bone spur, then reconstructed and fused the joint to prevent symptoms from any residual compression.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/10419f50-f7c3-4a51-973e-dd8b683e0da8/20-NEU-1875736_CQD_2_inset-805x703-1_jpg)

Figure 2. Osteophyte (C6) compressing the left vertebral artery (arrow).

The patient’s symptoms improved immediately postoperatively (Figure 3). He was discharged on postoperative day 5 and has since returned to normal mobility and function.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e0ac1f1f-f471-4163-954c-a2b4ed648233/20-NEU-1875736_CQD_3_inset-805x1190-1_jpg)

Figure 3. Postoperative angiogram showing a patent left vertebral artery upon turning the head to the left.

Bow hunter’s syndrome is a rare phenomenon in which physiologic head rotation causes bony elements of the spine to induce symptomatic vertebral artery compression. Most patients are fine with one functioning vertebral artery, and even some with both arteries occluded have sufficient flow from other areas to avoid symptoms. But a small subset of patients has an incomplete posterior communicating artery, an incomplete circle of Willis, a single vertebral artery or other uncommon issues that can cause this syndrome.

“In 15 years, I’ve seen maybe 10 cases,” says Dr. Krishnaney. “And I’ve been involved in almost all the cases here because I do both decompression and fusion surgery. It’s not something you see in everyday practice.”

Critical to an accurate diagnosis is the technical expertise of the angiography team. “Their comfort level with the dynamic angiogram made the difference here,” says Dr. Krishnaney. “In many places, that comfort level isn’t there, so the test isn’t routinely ordered.”

“When I saw that indentation on the angiogram, I was suspicious of rotational vertebrobasilar insufficiency syndrome,” says Dr. Hussain. “The history was also suspicious, and the dynamic angiogram is the confirmatory test that allowed us to see the extent of the occlusion during motion.”

Surgeons generally take two approaches to bow hunter’s syndrome: fusion to prevent motion or decompression to increase blood flow. This patient’s bone protruded from the back and pushed the artery forward, which left two options: approaching from the front and engaging the entire artery, or approaching from the back but doing both a compression and fusion.

Advertisement

“To salvage motion, we thought about going from the front, but the patient only had one vertebral artery, so it was risky,” explains Dr. Krishnaney. “And since his neutral angiogram showed some stenosis, a decompression alone wasn’t going to work. So I did both to maximize his chances of a good outcome and minimize risk to the artery itself.”

Few neurosurgeons perform both decompression and fusion surgeries; cerebrovascular surgeons tend to perform direct compressions, while spine surgeons handle fusions. Dr. Krishnaney performs both in consultation with cerebrovascular and stroke colleagues and credits Cleveland Clinic’s institute model with the collaboration that enabled this patient’s excellent outcome.

“We aren’t broken into silos here,” he says. “I perform both cerebrovascular and spine surgery. In consultation with my cerebrovascular and stroke colleagues, I choose the approach that’s best for the patient’s anatomy. It’s not based on the subspecialty to which the patient is referred. Dr. Hussain called me, we all had a look, and we were quickly able to determine the best approach. That kind of environment is critical to optimal patient care.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges