Patient experience improves with a multidisciplinary approach

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e3be362a-bd5f-42fd-be56-65a08b9dbefb/23-RHE-3662512-CQD-650x450-1_jpg)

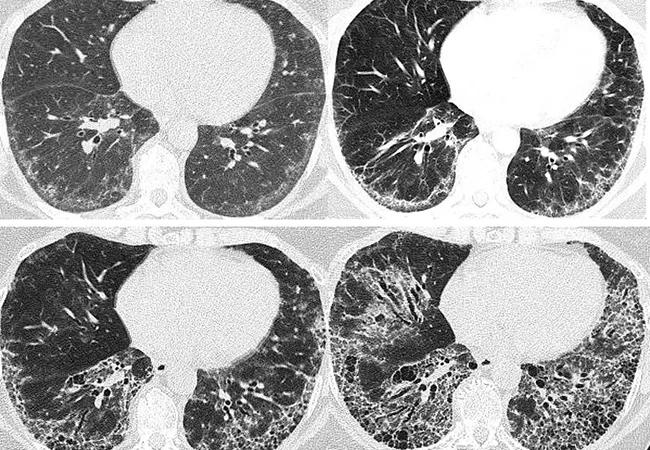

Scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease

Above, serial chest scans of a 57-year-old female with systemic sclerosis over eight years demonstrate the progression of interstitial fibrosis.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

By Soumya Chatterjee, MD, MS, FRCP

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) can be a prevalent and challenging pulmonary manifestation of systemic sclerosis (SSc), a rare autoimmune rheumatologic disease characterized by inflammation, fibrosis of the skin and internal organs, and an occlusive microvasculopathy.

Timely detection and delivery of therapy can be advantageous for patients with scleroderma‑associated interstitial lung disease (SSc-ILD) and the physicians who treat them. To facilitate this, a multidisciplinary approach — focusing on rheumatologists, pulmonologists, gastroenterologists and radiologists — should be used for diagnosing and assessing patients with SSc-ILD.

Patients with SSc have an increased mortality rate; a recent study in France reported a standardized mortality ratio of 5.73 among patients with SSc, with 28% dying within 10 years of diagnosis.1

Pulmonary complications such as pulmonary hypertension (PH) and interstitial lung disease (ILD) are the leading causes of death in patients with SSc. The prevalence of ILD in SSc may be as high as 52.3%,2 and although it can occur at any time, it is usually an early manifestation of SSc.

The course of SSc-ILD is variable. Although risk factors for the progression have been identified, such as a greater extent of fibrosis on HRCT and lower FVC, the disease course in an individual patient remains unpredictable.

As a systemic disorder, SSc has a heterogeneous range of manifestations: the lungs, kidneys, heart and gastrointestinal tract all may be affected, complicating disease management. Manifestations may include skin thickening, Raynaud’s phenomenon, ischemic fingertip ulcers, secondary Sjögren syndrome, musculoskeletal manifestations, gastrointestinal problems, and lung disease.

Advertisement

If pulmonary symptoms such as shortness of breath or a chronic dry cough are subtle or absent on initial presentation, then it is often a rheumatologist who will assess lung involvement. Patients often are referred to pulmonologists if they have pulmonary symptoms, bibasilar crackles on auscultation, lung abnormalities on a high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan, and/or impaired lung function on pulmonary function tests. It is important to note that even in combination with a chest X-ray, the physical examination has sub-optimal sensitivity to detect SSc-ILD, and should not be used as a screening strategy.

Patients with SSc-ILD commonly present with exertional dyspnea and cough, but some patients with early SSc-ILD are asymptomatic. As the extent of pulmonary involvement progresses, patients usually report fatigue and dyspnea on exertion and eventually at rest. In addition, chest auscultation may reveal dry crackles at the bases of the lungs.

Spirometry is non-invasive and cost-effective but has limitations in the setting of SSc-ILD. Assessment of forced vital capacity (FVC) lacks sensitivity, particularly in the early stages of the disease, given the wide range of normal values. Moreover, it may be falsely normal in patients with coexisting emphysema or falsely reduced in patients with extrapulmonary restriction.

An assessment of functional capacity should be performed during SSc-ILD diagnosis. A cardiopulmonary exercise test can provide excellent information on functional status and help predict patient outcomes, but it may not be feasible due to resource limitations. However, a simple six-minute walk test can be performed in the office, though extra-pulmonary factors may influence the six-minute walk test (arthritis, poor circulation, myopathy, or deconditioning).

Advertisement

Resting and walking oximetry should be considered in patients with respiratory symptoms or abnormalities in imaging or spirometry. The reliability of finger oximetry is compromised in patients with poor peripheral circulation or Raynaud’s phenomenon. An alternative site, such as the earlobe or a forehead probe, should be considered.

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) is the gold standard for diagnosing SSc-ILD. On HRCT, most patients with SSc-ILD have non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) pattern of lung injury, while a usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern is found in about 7.5% of cases.3 Ground-glass opacification (GGO) is the dominant feature of NSIP. It is usually symmetric in distribution, primarily subpleural, but can be diffuse, with a lower lobe predominance.During the early stages of SSc-ILD, prone images help differentiate between an increased density due to ILD and gravity-dependent atelectasis at the posterior lung bases.

Multi-compartment involvement in HRCT scans suggests an underlying autoimmune rheumatologic disease. Esophageal dilatation on HRCT scans is predictive of an SSc diagnosis. An increased diameter of the main pulmonary artery (MPA), or the ratio of the MPA diameter relative to that of the ascending aorta, indicates PH. A high MPA diameter and a segmental artery-to-bronchus diameter ratio above one in three to four pulmonary lobes has very high specificity for PH. Pulmonary venoocclusive disease (PVOD) is an essential consideration in SSc because PVOD-like involvement has been associated with a worse prognosis.

Advertisement

A surgical lung biopsy is rarely, if ever, required to establish a diagnosis of SSc-ILD. Given the morbidity and mortality associated with the procedure, surgical lung biopsy should only be performed in exceptional cases, such as to exclude malignancy or where there is a suspicion of PVOD.

Up to 90% of patients with SSc have GI tract involvement. Diagnosing and managing GI manifestations of SSc, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and esophageal dysmotility, is of paramount importance, as repeated microaspirations from poorly controlled GERD may lead to more rapid progression of ILD. A gastroenterologist with expertise in GI dysmotility should evaluate all patients with SSc early in the disease course.

A modified barium swallow can help rule out oropharyngeal dysphagia in patients with swallowing issues. Upper endoscopy is indicated in patients with dysphagia to identify GERD/esophagitis. Esophageal manometry should be considered to determine the severity of esophageal dysmotility in patients with esophageal dysphagia.

The high prevalence of ILD among patients with SSc, and the significant morbidity and mortality associated with SSc-ILD, make it essential to screen for SSc-ILD. Different approaches exist, but some form of advanced imaging is necessary, given the unreliable results of an approach based solely on physical examination, chest radiography and pulmonary function testing.

Protocols based on a limited number of slices seem to perform similarly to traditional HRCTs and are associated with radiation exposure similar to a plain chest X-ray. Lung ultrasound is operator-dependent, and its validity and reliability in detecting SSc-ILD require further investigation, but it performs well in the hands of experienced operators.

Advertisement

In a Delphi consensus study, experts in the field of SSc-ILD recommended that all patients with SSc be screened for ILD with thoracic HRCT as the primary tool, supported by assessment of symptoms, auscultation, and pulmonary function testing 4.

In addition, all patients with SSc without a diagnosis of ILD should be screened regularly with pulmonary function tests. Spirometry and carbon monoxide diffusing capacity (DLCO) should be assessed every three to six months for the first three to five years after diagnosis. Patients with SSc-ILD should be monitored closely to ascertain progression. Unfortunately, there is no established protocol for monitoring patients with SSc-ILD. Therefore, a multifaceted approach is required. It is generally recommended that symptoms, FVC and DLCO, and exercise-induced oxygen desaturation be assessed every six to 12 months, with repeated thoracic HRCT scans as clinically indicated. Information gained from these assessments should guide decisions about treatment initiation, change or escalation.

Diagnosis and assessment of SSc-ILD requires collaboration among, at a minimum, a rheumatologist, a pulmonologist and a radiologist. Assessment of the severity of ILD and risk factors for progression can have important implications for the patient’s monitoring, management and prognosis. Close collaboration between rheumatology and pulmonology may result in earlier referrals for therapies such as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and lung transplantation.

Given the systemic nature of SSc, a multidisciplinary approach is also essential for assessing other organ manifestations. A gastroenterologist should evaluate all patients with SSc early in the disease course. Patients with SSc and potential cardiac involvement should be evaluated by a cardiologist.

A multidisciplinary approach is necessary to ensure comprehensive care, which patients value.

Notes

1. Pokeerbux MR, Giovannelli J, Dauchet L et al (2019) Survival and prognosis factors in systemic sclerosis: data of a French multicenter cohort, systematic review, and meta-analysis of the literature. Arthritis Res Ther 21:86. doi.org/10.1186/s13075- 019-1867-1.

2. Bergamasco A, Hartmann N, Wallace L, Verpillat P (2019) Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis and systemic sclerosis-associated interstitial lung disease. Clin Epidemiol 11:257–273.

3. Yamakawa H, Hagiwara E, Kitamura H et al (2016) Clinical features of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia with systemic sclerosisrelated autoantibody in comparison with interstitial pneumonia with systemic sclerosis. PLoS One 11:e0161908. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.01619 08.

Advertisement

A review of treatment options for patients who may not qualify for surgery

Rising rates in young miners illustrate the need for consistent prevention messaging from employers and clinicians

Multidisciplinary focus on an often underdiagnosed and ineffectively treated pulmonary disease

Management and diagnostic insights from an infectious disease specialist and a pulmonary specialist

Treatments can be effective, but timely diagnosis is key

A Cleveland Clinic pulmonologist highlights several factors to be aware of when treating patients

A mindset shift has changed the way pulmonologists both treat and define PFF

Collaborative patient care, advanced imaging techniques support safer immunotherapy management