Impacts include major emphases on multidisciplinary teams, shared decision-making

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/873a5789-1508-4709-b6d2-167919558e61/23-HVI-4003412_aorta-illustration_650x450_jpg)

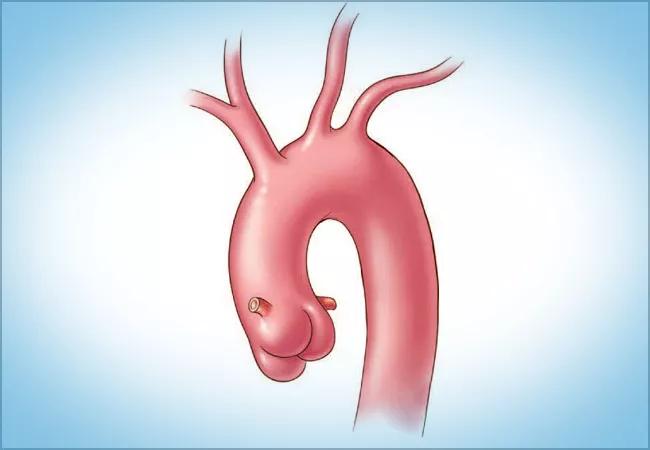

23-HVI-4003412_aorta-illustration_650x450

In the months since the 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease was issued late last year, the document has been welcomed by clinicians and patients alike.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Reception has been positive,” says Cleveland Clinic cardiologist Vidyasagar Kalahasti, MD, a member of the guideline writing committee. “My colleagues and other peers in the cardiovascular care community say the new guideline is pragmatic and its recommendations closely align with most of their practical experience.”

The guideline was developed to be more comprehensive and detailed than several previous American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines that it updated. Dr. Kalahasti, who serves as Director of the Cardiovascular Marfan Syndrome & Vascular Connective Tissue Disorders Clinic in Cleveland Clinic’s Aorta Center, has found it particularly helpful for instilling confidence in patients who face surgery for a genetically conferred aortic condition.

“When it comes to recommendations for operating on their particular mutation at a certain size, we show patients what the experts who worked on this guideline advise,” he explains. “They can see that it’s not just my opinion, but also that of my peers.”

The guideline was designed as a single, comprehensive resource that fills needs previously met by ACC/AHA guidelines on thoracic aortic disease, peripheral arterial disease and bicuspid aortic valve disease dating as far back as 2010. It is expressly intended to be used with the 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease.

An extensive body of research published since 2010 provided fertile ground for updating recommendations on all major aspects of aortic disease care: diagnosis, genetic evaluation and family screening, medical therapy, endovascular and surgical treatment, and long-term patient surveillance.

Advertisement

One area that received a major upgrade was discussion of the role of imaging in the assessment of aortic disease. Optimal imaging modalities and techniques for determining the presence and progression of aortic disease are explained in detail.

In assessing the need for surgery, the threshold for surgical intervention was lowered. Additionally, for patients who are shorter or taller than average, the standard method of indexing the aortic root or ascending aorta diameter to the patient’s body surface area was replaced by a recommendation to index a cross-sectional area of the aorta to the patient’s height. The newly recommended formula, pioneered by Cleveland Clinic cardiothoracic surgeon Lars Svensson, MD, PhD, was enthusiastically embraced by the writing committee.

“Body surface area changes if a patient gains or loses weight, but an adult’s height is fairly stable,” Dr. Kalahasti explains. “Indexing the patient’s aorta diameter to their height provides a better discriminator for the timing of intervention in patients with and without heritable conditions. As a result, some patients will need surgery earlier.”

“As a cardiac surgeon who subspecializes in the treatment of aortic disease, I have found the ACC/AHA guideline useful when counseling patients on timing for surgical intervention,” notes Patrick Vargo, MD, staff in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.

The guideline is likewise notable for its emphasis on new recommendations for comprehensive care that prioritize the role of shared decision-making and the importance of an experienced multidisciplinary care team. The latter emphasis reflects an approach long validated at Cleveland Clinic.

Advertisement

“Other institutions are recognizing the need for a multidisciplinary evaluation of these patients, and patients themselves increasingly realize that this is a team sport,” Dr. Kalahasti says. “No single physician can manage the medical, genetic and surgical sides of aortic disease.”

The guideline promotes substantial flexibility in treatment decisions through shared decision-making. The process requires active dialogue between patients and members of their care team.

Dr. Kalahasti cites the example of a patient with a bicuspid valve and an aorta 5.2 cm in diameter, but no other risk factors, who does not want to wait until the aorta reaches 5.5 cm to have surgery. According to the guidelines, it is not unreasonable to do elective surgery now, so long as the patient understands the pros and cons of surgery versus continued surveillance.

“We tried to reflect nuances and not be absolutists,” Dr. Kalahasti says. ““It is a great advance that we have given patients permission to discuss options with their physician and then decide on a course of action.”

The wealth of information published in the past decade or so on specific genetic mutations and their genotype and phenotype differences contributed to a robust set of recommendations for patients with these mutations and the clinicians who treat them.

“For patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome, for example, we now know that certain mutations may not confer the same high degree of risk as other genetic mutations,” Dr. Kalahasti notes.

He adds that mounting detail on specific genetic conditions — addressed in the new guideline — has resulted in earlier referrals for surgery, which he identifies as a positive development. “In patients with genetically mediated diseases, the aorta can dissect at a small size,” he says. “One way to prevent this catastrophic event is to do elective surgery.”

Advertisement

“The continued explosion of knowledge about gene mutations associated with aortic dissections and ruptures helps us tailor care to each individual patient,” adds Dr. Vargo the surgeon, “and the most recent data are captured in this updated guideline.”

Indeed, the Marfan Foundation, the John Ritter Foundation for Aortic Health and other organizations that advocate for individuals with heritable aortic diseases are highlighting the guideline to increase awareness among patients.

The breadth and depth of changes made to the various ACC/AHA guidelines that the new document supersedes made it clear that more frequent updates would benefit patient care. As a result, the writing committee plans to reconvene in a few years to review the literature published since these 2022 guidelines and decide whether another update is warranted.

Meanwhile, Dr. Kalahasti encourages cardiologists and even primary care physicians to familiarize themselves with the 2022 guideline so they can refer appropriate patients. “A large share of my practice is based on incidental diagnoses made by primary care doctors from imaging tests ordered for other conditions,” he says. “When an enlarging aorta is found early on, that’s when we are best positioned to effectively manage it.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

New Cleveland Clinic data challenge traditional size thresholds for surgical intervention

Study finds comparable midterm safety outcomes, suggesting anatomy and surgeon preference should drive choice

New review distills insights and best practices from a high-volume center

Blood test can identify patients who need more frequent monitoring or earlier surgery to prevent dissection or rupture

Recent Cleveland Clinic experience reveals hundreds of cases with anatomic constraints to FEVAR

Multicenter pivotal study may lead to first endovascular treatment for the ascending aorta

Residual AR related to severe preoperative AR increases risk of progression, need for reoperation

Large cohort study finds significant effect in men and nonsmokers