Indication, timing and options for surgical intervention

Podcast content: This podcast is available to listen to online.

Listen to podcast online (https://www.buzzsprout.com/2237537/17380999)

Podcast content: This podcast is available to listen to online.

Listen to podcast online (https://www.buzzsprout.com/2237537/17422333)

Bicuspid aortic valve, the most common form of congenital heart disease in the U.S., produces a range of complications with varying severity. When valve leaflets don’t open fully, blood flow leaving the heart can be restricted. When valve leaflets don’t close tightly, regurgitation can develop. In up to 50% of people with bicuspid aortic valve, the aorta weakens and enlarges over time.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“These are the ‘big three’ complications of bicuspid valve,” says Brian Griffin, MD, Section Head of Cardiovascular Imaging at Cleveland Clinic and Medical Director of its Valve Center. “I see hundreds of patients with these problems every year.”

In a recent two-part episode of Cleveland Clinic’s Cardiac Consult podcast, Dr. Griffin and Lars Svensson, MD, PhD, Chief of the Heart, Vascular and Thoracic Institute at Cleveland Clinic, discuss their experience and outcomes in managing bicuspid aortic valve. They touch on topics including:

Click the podcast players above to listen to the two-part podcast now, or read on for an edited excerpt. Check out more Cardiac Consult episodes at clevelandclinic.org/cardiacconsultpodcast or wherever you get your podcasts.

Lars Svensson, MD, PhD: What treatments do you discuss with your patients based on their age? As you know, younger patients typically have a regurgitant valve. As patients get into their 40s and 50s, we start seeing bicuspid valve and stenosis. What do you recommend for patients as far as valve replacement or repair?

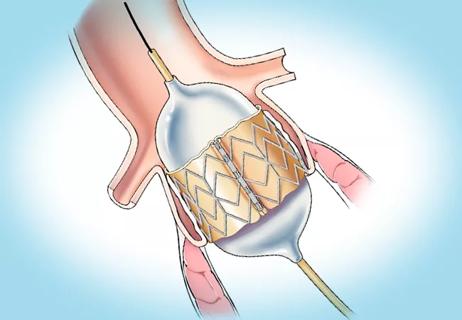

To go back to what you were saying about TAVR [transcatheter aortic valve replacement], the stroke rate is higher with TAVR and bicuspid valves. The paravalvular leak rate is higher. The root is very different, and the valve symmetry is different in patients with bicuspid valves. That’s partly the reason why TAVR doesn’t do as well in bicuspid valves, apart from the fact that patients are typically younger and then come back with problems.

Advertisement

What do you say to your patients based on age and long-term, lifelong management of their valves?

Brian Griffin, MD: I certainly see a lot of patients at various ages. I think when somebody is over the age of 60 and they have a stenotic valve, or even a regurgitant valve, the bioprosthesis has a good track record. It offers the potential for doing a valve-in-valve in the future. We usually try to ensure that the last procedure this type of patient has is a TAVR-type procedure, when they’re relatively old, when open surgical procedures might be somewhat more uncomfortable or risky for them.

The bioprostheses that we have typically used at the aortic position have been bovine pericardial. We have a series of over 12,000 patients that showed better-than-expected durability with those types of valves.

In younger patients, people in their 20s or 30s, it is a trickier problem. If you go with the bioprosthesis, you’re potentially exposing the patient to multiple future operations and procedures. One way of trying to get around this is to put in a mechanical valve.

When I came to Cleveland Clinic 30 years ago, at least half of the valves we put in were mechanical. Now, I would say it’s about 10% or less. Some of that is due to a change in population, but some of it is due to the improvement in bioprostheses and patients’ distaste for being on an anticoagulant — particularly people who have occupations or hobbies (like mountain biking) where they’re exposed to risk.

Although a mechanical valve is a very good option for younger people, I find that not many people want to go that route. The results with mechanical valves have been very good, and some last for a very long time. We try to educate the patient as to what’s available and then help the patient make their own decision on what’s best.

Advertisement

There are other approaches in younger patients, one of which would be to put in a homograft valve, which we tried for quite a few years. That’s a human valve. However, it wasn’t associated with better long-term outcomes.

We also could do the Ross procedure, where you take the patient’s own pulmonary valve, put it in at the aortic position where it’s possibly most needed, and then put in a human valve at the pulmonary position. It’s a big, two-in-one operation. The results in bicuspid valves have not always been favorable, particularly in patients with aortopathy. So, it fell in favor and then out of favor. It’s making a little comeback, but we don’t have long-term data to suggest that it is something we should do.

In addition, we have the ability to do the Ozaki procedure. It’s a Japanese technique where the patient’s own pericardium is made into a bioprosthetic valve, the advantage being that the patient’s own native tissue is being used. Again, we don’t have long-term data on the success of that.

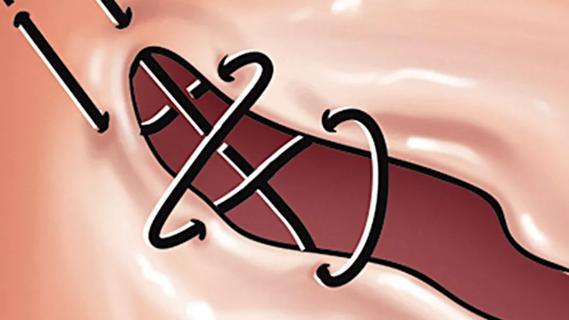

One thing I’ve liked over the years in younger patients who have a very leaky valve — particularly where they have a big prolapsing leaflet, where the leaflet is not very stenotic and where there isn’t a lot of calcium on it — is to repair the valve. Our results with repair have been quite good. Durability in many instances is as good if not better than a bioprosthesis while leaving the patient with their own valve. I think bicuspid valve repair in expert hands is a very good technique. I have had patients whose repairs have lasted longer than 20 years.

Advertisement

However, while a repaired valve is no longer leaking, it eventually may calcify and become stenotic and then require another intervention. But for a young person who doesn’t want to be on warfarin and who wants to maintain a relatively normal lifestyle, a bicuspid valve repair can be a very good option.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Join us in New York City Dec. 5-6

30-year study of Cleveland Clinic experience shows clear improvement from year 2000 onward

Study examines data and clinical implications for performing Ross procedures in infancy versus later in life

Large retrospective study supports its addition to BAV repair toolbox at expert centers

Choice between smaller or larger prosthesis is a tradeoff between leak and pacemaker risks

4-D imaging informs complex aortic valve repair in adult and pediatric patients

Study offers guidance on an increasingly common presentation

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches