Age and other factors figure into the choice among SAVR, TAVR, Ross, Ozaki and more

Aortic valve replacement (AVR) has evolved into a treatment that can be offered as a range of options. Cardiac surgeons and interventional cardiologists performing AVR must have extensive expertise and experience to understand which option is the most appropriate for an individual patient. Skill in carrying out the procedure and diligence in follow-up are required to minimize complications.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

At Cleveland Clinic, patients are advised about AVR by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a cardiovascular imaging specialist, an interventional cardiologist and a cardiac surgeon, sometimes with other clinicians as well. Additionally, specialized data coordinators assemble data on each patient to allow for ongoing assessment of outcomes.

Procedural mortality rates of 0% to 0.5% for surgical AVR (SAVR) and of 0.3% to 0.6% for transcatheter AVR (TAVR) in recent years validate this approach, says Samir Kapadia, MD, an interventional cardiologist who chairs Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Cardiovascular Medicine. “These outcomes demonstrate that we are selecting patients appropriately for both procedures,” he says.

Under Cleveland Clinic’s group practice model, staff are not paid based on procedural volumes. This, together with the structure of its Heart, Vascular and Thoracic Institute integrating surgeons and cardiologists in shared spaces under unified leadership, aligns incentives in the interest of the patient rather than individual providers or specialties. Medical and surgical specialists have collaborated for decades to provide each patient with the optimal solution to their valve problem.

“Our heart team is truly multidisciplinary,” notes cardiac surgeon Faisal Bakaeen, MD. “It’s not just the interventional cardiologist performing the TAVR or the surgeon performing the SAVR, but also the cardiologist who sees and follows the patient and the imaging specialist who provides us with precise measurements of the valve, root and annulus. This enables us to consider each patient as a unique case, discuss the pros and cons of SAVR and TAVR with them and recommend the ideal therapy for their individual needs. The patient then has the final say.”

Advertisement

The breadth and depth of valve replacement expertise make the multidisciplinary team ideally suited for complex patients, many of whom have serious comorbid illnesses complicating their aortic valve stenosis, such as coronary artery disease (CAD). Experience enables the team to adjust their approach to maximize success.

“When a patient has extensive CAD involving the left anterior descending artery and multiple vessels, we lean toward open valve replacement and concomitant coronary artery bypass grafting,” Dr. Bakaeen explains. “If a patient has a low burden of CAD or if unimportant vessels are affected and the patient is frail, we do TAVR and manage the CAD medically. In not-so-robust patients with significant affected arteries, we recommend TAVR and stenting. We believe the key is to be as comprehensive as possible in treatment options.”

When a patient presents with aortic stenosis or other aortic valve disease, the first step is to thoroughly assess their condition. Cleveland Clinic goes beyond conducting a hemodynamic assessment with echocardiography to assessing anatomy and function with CT or MRI. “These assessments are not commonly done elsewhere, but we feel they are very important,” Dr. Kapadia notes.

The imaging studies are used to assess whether the valve is bicuspid or tricuspid and whether calcifications are present. The team considers annulus size, the health of the aorta and coronary arteries, the degree of left ventricular function, and the presence of any atrial fibrillation, fibrosis, scarring or pulmonary hypertension. “All these things can be the consequence of aortic stenosis or may occur in addition to stenosis,” Dr. Kapadia explains.

Advertisement

The optimal approach to AVR for an individual is based on the life expectancy of the patient and the durability of the valve.

Patients with aortic stenosis in their 20s through 50s have many different options, depending on their anatomy, lifestyle and other cardiac conditions and comorbidities. SAVR with a bioprosthetic valve or SAVR with a mechanical valve are the most commonly offered options. Each has its drawbacks, however: Bioprosthetic valves have limited durability in younger patients, and mechanical valves last longer than bioprosthetic valves but require lifelong anticoagulation and are associated with complications such as bleeding and stroke.

A better option for patients in their teens to age 30 often is the Ross procedure, says cardiac surgeon Shinya Unai, MD. During a Ross procedure, the aortic valve is replaced with the patient’s own pulmonary valve, and the pulmonary valve is replaced with a donor homograft (Figure 1). Anticoagulation is not required. “The Ross procedure has shown excellent durability and excellent valve performance in young patients,” Dr. Unai notes, although it carries a risk of reintervention on two valves.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5c328bcc-1486-4ae8-a25b-8144ec5c0808/ross-procedure)

Figure 1. Key steps in the Ross procedure. (A) The pulmonary valve is harvested and the diseased aortic valve is removed. (B) The pulmonary valve autograft is implanted to replace the aortic valve. (C) The coronary artery is reimplanted to the autograft and a pulmonary valve homograft is implanted. (D) Completion of the procedure.

“A Ross procedure should last 20 to 30 years or more if a perfect technical result is achieved in the operating room,” adds cardiac surgeon Marijan Koprivanac, MD.

“We have improved our techniques for performing the Ross procedure since the 1990s,” says Dr. Unai, who often adds procedural steps to further support the autograft. These include annuloplasty to support the annulus, wrapping the entire autograft with native aortic root tissue and replacing a short area of ascending aorta to stabilize the distal autograft. “This potentially allows us to offer the Ross procedure to patients traditionally thought to be less ideal candidates for it,” he explains.

Advertisement

Patients who are on multiple antihypertensive medications may not be ideal candidates for the Ross procedure. “Blood pressure must be controlled well, because the pulmonary valve is not accustomed to high pressures,” Dr. Unai notes.

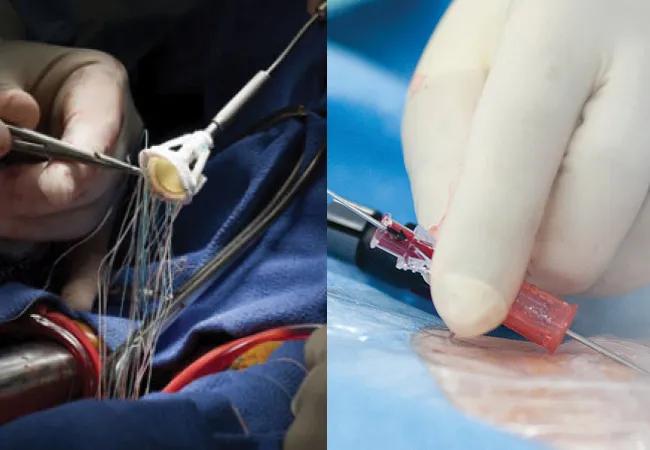

An alternative option in young patients is the Ozaki procedure. In this operation, the leaflets of the aortic valve are removed, after which new leaflets are fashioned from glutaraldehyde-treated pericardium and sewn onto the annulus (Figure 2). Benefits of the Ozaki procedure are that it does not require anticoagulation and provides a larger valve opening compared with the opening provided by prosthetic valves.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a0802315-5558-439d-911d-8e303b44a99a/ozaki-procedure)

Figure 2. Photo of a completed Ozaki procedure.

“When I see young patients, I discuss both the Ross and Ozaki procedures as options,” says Dr. Unai, who has performed one of the highest volumes of Ozaki procedures in the U.S. “My team is always prepared to do both procedures. Intraoperatively, if we find that the patient’s pulmonary valve is not suitable for the Ross procedure, the Ozaki procedure may be a better option. Alternatively, when the aortic root anatomy is not suitable for the Ozaki procedure, we can convert to a Ross procedure.”

Although some centers may offer the Ross procedure beyond age 60, Dr. Unai says the risks are not justified in this population.

“The Ross is technically complex,” Dr. Koprivanac adds. “We can do it safely — we have had no operative deaths with either the Ross or the Ozaki — but we need to use our judgment. We cannot compromise a patient’s health.” He notes that minimally invasive SAVR with a biologic valve may sometimes be more appropriate, as it carries a very low risk of reoperation, equivalent to a first operation at Cleveland Clinic, and also can be a good platform for valve-in-valve TAVR in the future when the valve degenerates.

Advertisement

Healthy, active patients in their 60s or early 70s should undergo SAVR, the surgeons say. If CT shows a small root or annulus, it should be enlarged. If the patient is tall or large, a larger valve is needed, even if the aortic root size is normal. “The valve must be sized relative to body size or patient-prosthesis mismatch is likely to occur,” Dr. Koprivanac explains. “Otherwise, the patient’s symptoms will not resolve and the valve will fail over time more quickly. Enlarging the root or annulus will set the patient up better for a future TAVR if needed.”

“The last intervention in life should be TAVR, because you want to avoid operating on patients when they are elderly,” Dr. Kapadia says. “Another consideration is to plan for one valve-in-valve procedure in the future and ideally avoid two valve-in-valve procedures resulting in three valves being present in the aortic position.” Anatomy of the aortic root, the patient’s life expectancy and the choice of prosthesis all help guide the best strategy for future therapies.

Biologic surgical and transcatheter valves are expected to last 10 to 15 years. At age 75, TAVR can be offered if another TAVR valve can be placed inside it if the patient reaches age 85. If the patient is healthy and a large surgical valve can be placed at age 75 for future TAVR in a surgical valve, this can be an optimal strategy also. “Anatomy, comorbidities, opinions of our surgical and interventional experts, and patient preferences guide us to decide the optimal strategy,” Dr. Kapadia says.

In their mid-70s or 80s, patients can undergo a TAVR-in-SAVR procedure and expect results comparable to a first-time TAVR. “The long-term durability of TAVR-in-TAVR is still uncertain, but patients who have SAVR first, followed by TAVR, do well,” Dr. Koprivanac says.

The contemporary standard of care for SAVR is partial sternotomy (“J” incision) or mini-thoracotomy. Recovery is two to five days in the hospital, and patients return to normal activity more swiftly than with classic open sternotomy.

“Patients in their 80s who are physically strong and have good muscle mass are at low risk from SAVR and tend to do well after surgery, which often can be done with a minimally invasive approach,” Dr. Koprivanac says. “We present all options, with their pros and cons, to patients and their families. The final choice, if both options will yield similar results and safety, is the patient’s.”

Advertisement

JACC State-of-the-Art Review details current knowledge and new developments

Optimally timed valve replacement depends on an expert approach to nuanced presentations

Large longitudinal study supports earlier intervention over clinical surveillance

Series of 145 patients characterizes scope of presentations, interventions and outcomes

New Cleveland Clinic data challenge traditional size thresholds for surgical intervention

Study finds comparable midterm safety outcomes, suggesting anatomy and surgeon preference should drive choice

New review distills insights and best practices from a high-volume center

When to recommend aortic root surgery in Marfan and other syndromes