Despite the complexity, surgery can be safe and effective

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ab226ce4-542b-47c9-b271-95176b08795a/16-HRT-2447-LVOTO-CQD-650-Feat_jpg)

LV Outflow Tract Obstruction After Mitral Valve Replacement: Two Cases, Same Principles for Success

By Nicholas G. Smedira, MD, and Robert J. Steffen, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO), both fixed and dynamic, can be caused by many factors. Two of our recent cases display a fixed pattern of severe obstruction secondary to completely retained in situ anterior mitral valve leaflet.

A 58-year-old woman underwent an attempted mitral valve repair for degenerative mitral disease at an outside institution. Multiple attempts at valve repair were followed by bovine mitral valve replacement with complete retention of the anterior leaflet. Her postoperative course was prolonged because of cardiogenic shock requiring temporary mechanical support and the need for tracheostomy. A year later, she had persistent heart failure symptoms including fatigue, dyspnea on exertion, fluid retention and weight gain.

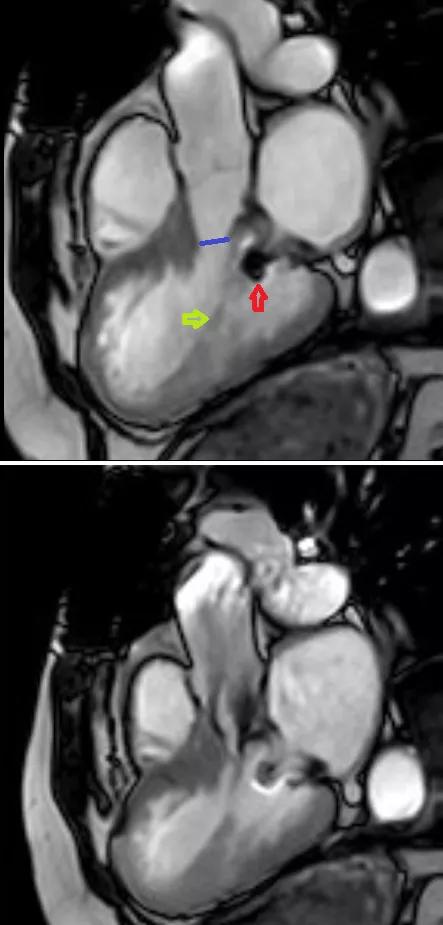

An echocardiogram performed at Cleveland Clinic showed a fixed, elevated gradient across her LVOT secondary to retained anterior mitral leaflet. Her resting LVOT gradient was 52 mm Hg. The gradient increased to 56 mm Hg with Valsalva maneuver and 70 mm Hg with stress. The interventricular septum was noted to be 1.5 cm. There was no paravalvular leak or mitral regurgitation. Cardiac MRI confirmed the outflow obstruction secondary to a completely retained leaflet and subvalvular apparatus (Figure 1).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a0020125-55c0-4fc6-9efc-04bb72744625/16-HRT-2447-LVOTO-CQD-Inset-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Cardiac MRIs from the first patient. Top image demonstrates a narrow left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) (blue line) in diastole. Its diameter is 9 mm at the narrowest point, in contrast to 24 mm at the level of the aortic valve. Red arrow indicates the prosthetic mitral valve strut; yellow arrow indicates chordae to the retained anterior mitral leaflet. Bottom image demonstrates turbulent flow through the LVOT in systole.

Advertisement

A 69-year-old woman had undergone mechanical mitral valve replacement as well as coronary bypass at an outside institution in 2002. She had known for a few years that she had an elevated LVOT gradient. Recently she had developed worsening chest pain and dyspnea on exertion with occasional rest symptoms. Cardiac catheterization confirmed that her bypass grafts were patent without any new coronary artery disease.

A transesophageal echo (TEE) demonstrated turbulent flow in the subaortic area, with a peak gradient of 155 mm Hg. Her aortic valve was normal. There was no paravalvular leak or mitral regurgitation. The width of her septum was 1.5 cm. The echo demonstrated the cause of her gradient to be the retained valve and subvalvular apparatus, with chordal attachments extending into the LVOT.

Although the presentation of each patient was unique, the challenge of widening the outflow tract without removing the prosthetic valve was similar. Both procedures were performed using the transaortic approach we use to treat patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy.

Through a transverse aortotomy just above the sinotubular junction, the LVOT and its contents were assessed. This view also allowed for visualization of the antero- and infero-interventricular septum, papillary muscles, chordae and anterior mitral leaflet.

In the first patient, the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve was completely removed from around the sewing cuff and struts of the biologic prosthesis (Figure 2). The anterolateral papillary muscle was found to have a prominent head, which was removed. Lastly, a 3-g myectomy of the anteroseptum was performed. Postoperative TEE demonstrated a wide-open LVOT with no dynamic obstruction on administration of dobutamine and nitroglycerine (Figure 3). No paravalvular leak was noted around the prosthesis. The patient was extubated on postoperative day 0 and discharged on day 5.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/babbd8fa-599e-4ce0-9818-4c7b095f38c4/16-HRT-2447-LVOTO-CQD-Inset-2_jpg)

Figure 2. Photo of the explanted anterior mitral leaflet, chordae and papillary muscle that was retained at the time of mitral valve replacement in the first patient.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/bafb2331-04c9-4502-a10b-97d5740b1c1b/16-HRT-2447-LVOTO-CQD-Inset-3_jpg)

Figure 3. Postoperative transesophageal echocardiogram of the first patient showing laminar flow through the left ventricular outflow tract.

Similarly, in the second patient the remnant of the anterior mitral leaflet was resected. A severely hypertrophied head was removed from both anterolateral and posteromedial papillary muscles. Lastly, a 5-g septal myectomy was performed. This patient had developed atrial fibrillation as well, so a concomitant CryoMaze procedure was performed. As before, postoperative TEE demonstrated a wide-open outflow tract with no dynamic obstruction or paravalvular leak.

These cases demonstrate key aspects of investigation and operating on patients with LVOTO after previous mitral valve replacement. Both operative reports detail complete in situ retention of the anterior leaflet, suggesting a possible mechanism for the obstruction. Maintaining continuity between the annulus and left ventricle through chordal-sparing techniques is important in preserving late left ventricular function in patients undergoing mitral replacement. These cases show, however, the importance of completely detaching the anterior leaflet from the annulus, excising the central portion and positioning the remnants of the valve at or below the commissure level (below the 3 and 9 o’clock positions as viewed through the left atrium).

Advertisement

Identifying LVOT pathology in patients with a mitral prosthesis in place can be very difficult using traditional transthoracic echocardiography. In our first patient, MRI was used as an adjunct to identify retained chords from the in situ anterior mitral leaflet. In our second patient, TEE was used to visualize the retained subvalvular apparatus and identify it as the cause of the high gradient.

Performing these operations through a transverse aortotomy greatly simplifies the surgery. Direct visualization of the outflow tract allows the surgeon to confirm the cause of obstruction and intervene as indicated on the hypertrophied septum, papillary muscles and anterior mitral leaflet. Both patients were treated using limited cardiac dissection and without re-replacing the mitral prosthesis, saving significant time and reducing the risk of complications. As a result, the cross-clamp time without the maze procedure was only 20 minutes. Both patients were extubated within 24 hours, left the ICU one day after surgery and had an uneventful recovery.

LVOTO entails a complex interplay of all components of the ventricle. Surgeons must be cognizant that the anterior mitral leaflet and its subvalvular apparatus can lead to LVOTO if not detached and moved at the time of mitral valve replacement. Surgery for LVOTO in the setting of a mitral prosthesis can be done safely and effectively with good outcomes.

Dr. Smedira is a cardiothoracic surgeon and Dr. Steffen is a cardiothoracic surgery fellow, both in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery.

Advertisement

Advertisement

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches