Benefits of new FDA safety determination go beyond expanding patients’ options

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/9887e740-d10e-4bc3-9236-24019fc1a0d0/21-HVI-4131174-CQD-Paclitaxel-coated-devices-for-PAD_jpg)

21-HVI-4131174-CQD-Paclitaxel-coated-devices-for-PAD

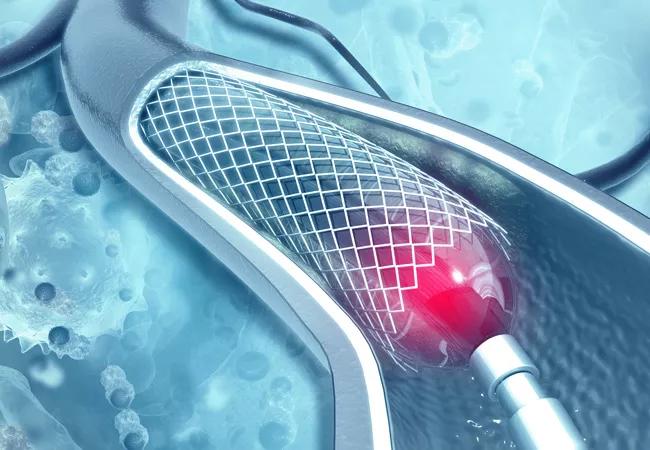

When the FDA announced in July that it determined paclitaxel-coated devices are not associated with excess mortality risk for patients with atherosclerotic lesions in the femoropopliteal artery, the decision did more than expand many patients’ treatment options. It also established a promising model for how the FDA, physicians and the medical device industry can collaborate to efficiently address pressing clinical questions. It even appears to be improving how vascular surgery trials will be conducted moving forward.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

That’s the perspective of Sean Lyden, MD, Chair of Vascular Surgery at Cleveland Clinic. “The FDA’s decision came in the wake of a flood of research and effort to ensure that the vascular surgery and vascular medicine communities were putting our patients’ safety first,” says Dr. Lyden, who is a member of the board of directors of the not-for-profit VIVA Foundation, which helped coordinate much of the FDA/physician/industry collaboration to scrutinize the safety of paclitaxel-coated devices.

“This represents a huge win that involved getting all the players together to thoroughly examine all the data and get answers for our patients,” he continues. “The FDA should be applauded for the speed of their reaction and their sustained collaboration with physicians and industry. Vascular surgery research has evolved for the better as a result of this experience.”

The FDA decision came in the form of a July 11, 2023, update letter to healthcare providers that states the following: “Based on the FDA’s review of the totality of the available data and analyses, we have determined that the data does not support an excess mortality risk for paclitaxel-coated devices.”

The suggestion that these devices were perhaps associated with such a risk arose from a meta-analysis published by Katsanos and colleagues in December 2018. These researchers pooled summary-level data from 28 randomized controlled trials of paclitaxel-coated balloons and stents for treating femoropopliteal peripheral artery disease (PAD). They reported a significantly increased rate of all-cause death at two and five years in patients with claudication who received paclitaxel-coated devices (relative to controls), as well as a potential dose-related signal.

Advertisement

These findings prompted the FDA to update labeling for paclitaxel-coated devices in 2019 and to advise providers that “alternative treatment options should generally be used for most patients” while the agency further studied the question.

The findings also prompted controversy, in view of the lack of a plausible mechanism of harm and the fact that up to 30% of patients had been lost to follow-up, as the studies in the meta-analysis were not designed to assess long-term mortality. A subsequent meta-analysis (Circulation. 2020;141:1859-1869) was conducted that used individual patient-level data and captured more of the patients lost to follow-up. That analysis, facilitated by VIVA and co-authored by Dr. Lyden, showed a smaller increase in mortality with the paclitaxel-coated devices relative to the summary-level meta-analysis and showed no dose-response relationship.

Meanwhile, the FDA continued to work with physicians and device manufacturers on analysis plans as data continued to accumulate from additional studies and from longer follow-up and more-complete vital status information from prior studies. This culminated in an updated patient-level meta-analysis with follow-up ranging from two to five years, “with data from most studies available out to five years,” as stated in the FDA’s July update letter. The letter concluded that “the updated RCT meta-analysis does not indicate that the use of paclitaxel-associated devices is associated with a late mortality risk.”

The updated meta-analysis with patient-level data, which will soon be published in a peer-reviewed journal, “was the tipping point for FDA,” Dr. Lyden says. “It proved that the initial meta-analysis was flawed due to incomplete data. But when the safety signal was first suggested, we did the right thing for patients. Usage was restricted and we studied the question as thoroughly as possible. And the concern was ultimately proven unfounded.”

Advertisement

The FDA will now work with manufacturers of paclitaxel-coated devices to revise their labels to remove warnings about potential late mortality risk and remove any use restrictions that were added after their initial indications. But that will take several months, and raising broad awareness of the changes will take even longer, Dr. Lyden suspects.

“At Cleveland Clinic, we’ve already gone back to using drug-coated devices as our primary therapy for appropriate patients, because we did not see any suggestion of a late mortality risk as more data accumulated,” he says. “And it’s well established that use of drug-coated devices increases the chance of vessel patency by 30% at one and two years, with sustained benefit out to five years.”

He adds, however, that there’s more hesitancy in community practice, especially in light of the FDA’s initial 2019 guidance to use alternative therapies for most patients. “Physicians were told to use these devices only for high-risk lesions in high-risk patients, but ‘high risk’ was never defined,” he explains. “As a result, many physicians were wary of using them at all.”

Dr. Lyden suspects it will take a year or two — and consistent education of providers — for use of paclitaxel-coated devices to return to levels before the safety question was raised. “Once a warning is out there, it’s difficult to walk it back,” he says. “Yet that’s what the FDA did, which makes their commitment to resolving this issue all the more remarkable.”

His Cleveland Clinic colleague Aravinda Nanjundappa, MBBS, MD, concurs about the significance of the updated FDA decision. “Establishing the long-term safety of paclitaxel-eluting balloons and stents has changed the scope of practice for the endovascular management of PAD,” says Dr. Nanjundappa, staff cardiologist in the Section of Invasive and Interventional Cardiology. “Long occlusive femoropopliteal segments can be safely and effectively treated with low restenosis-improved outcomes. Ongoing and future research regarding the safety and efficacy of drug-coated devices for critical limb ischemia will accelerate wound healing, reduce amputations and save lives.”

Advertisement

“The FDA update is timely and likely reflects reevaluation of newer data and reexamination of previous data,” adds another colleague, Scott Cameron, MD, PhD, Section Head of Vascular Medicine. “A not infrequent issue we encounter is that agencies or clinicians not trained in research may be swayed by lower-quality observational data published by a very talented author. Clinical decision-making, where possible, should always be based on high-quality randomized controlled trials and primary mechanistic research.”

Meanwhile, the episode has yielded broader positive changes in at least three aspects of vascular surgery research, according to Dr. Lyden:

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advanced OCT features may help individualize treatment intervals

3 specialists share multidisciplinary perspectives on a widely impactful cardiovascular condition

Innovative approach to the procedure can yield significant relief in complex cases

A scannable recap of our latest data in these clinical areas

Site visits offer firsthand lessons in clinical and operational excellence in cardiovascular care

New insights on effectiveness in patients previously treated with other anti-VEGF drugs

Study identifies factors that may predict vision outcomes in diabetic macular edema

Early learnings on use of the minimally invasive alternative to surgical bypass