A look at where TCAR and transfemoral carotid stenting are likely headed

With the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) expected to update its National Coverage Determination (NCD) on carotid artery stenting (CAS) later this year, utilization of this less-invasive alternative to carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for atherosclerotic bifurcation carotid disease may be poised to grow substantially.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The current NCD limits CMS payment for carotid stenting procedures to patients deemed to be at high risk from CEA. Numerous medical and surgical societies contend that since the NCD was last reconsidered in 2009, significant advances in CAS technology and techniques, standards for operators and facilities, and patient selection have brought outcomes with CAS to a level of noninferiority with CEA for appropriate patients. These groups and many clinicians have therefore called on CMS to expand its coverage of CAS to patients with standard surgical risk, to parallel its coverage of CEA.

Such a change would likely fuel greater use of stenting for patients needing intervention for carotid disease, both traditional transfemoral CAS and the direct-access approach of transcarotid artery revascularization (TCAR).

The timing of expanded reimbursement this year could be particularly fortuitous for TCAR. “Studies that have come out in the past year and a half have shown just how safe TCAR is and how effective it can be in treating a broad range of patients,” says Cleveland Clinic vascular surgeon Norman Kumins, MD, who has been performing TCAR since 2015 and participated in the ROADSTER pivotal trials that supported FDA approval of the one TCAR system currently commercially available in the U.S., the ENROUTE® Transcarotid Neuroprotection System.

TCAR represents a hybrid approach to CAS that involves a small incision at the base of the neck. A puncture is made in the proximal ipsilateral common carotid artery to allow stent deployment using a specialized arterial sheath to allow blood flow away from the brain and return it to a vein in the groin. This method of protection from stroke is known as dynamic flow reversal, in contrast to a traditional embolic filter approach that traps debris distal to the treated lesion.

Advertisement

“TCAR avoids the need to traverse the vasculature all the way from the groin, including avoidance of aortic arch manipulation,” notes Cleveland Clinic vascular surgeon Francis Caputo, MD. “Compared with transfemoral carotid stenting, it’s a simpler procedure that allows direct access to the carotid artery without risk of multiple passes or multiple opportunities to introduce embolic risk. It has shown excellent results so far but has not been compared to traditional CEA in a randomized study. We don’t have long-term data on it yet.”

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/b370b5c8-018d-4889-b016-f641e157125d/23-HVI-3848958-CQD-Inset-Pre-Post-TCAR_jpg)

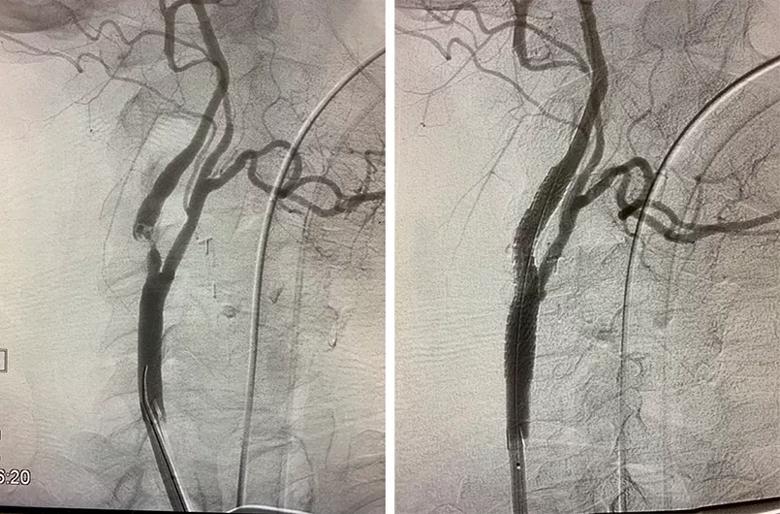

Images of the carotid bifurcation in a typical patient before (left) and after (right) the TCAR procedure.

But the available shorter-term data with TCAR reveal one of its chief advantages, according to Dr. Kumins: a low rate of stroke in the ROADSTER and ROADSTER-2 clinical trials (between 0.8% and 1.4%), which compares favorably with stroke risk for both CEA and commercially available transfemoral CAS options.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/1cb5dc10-33a6-4fee-b631-4fd928aaa954/23-HVI-3848958-CQD-Inset-TCAR-filter_jpg)

Photo of a filter that trapped debris during a TCAR procedure that otherwise might have embolized to the brain.

Another advantage of TCAR is its relative simplicity, which leads to an additional benefit over transfemoral CAS: a short learning curve, with providers typically becoming proficient performing TCAR within five to 10 procedures. “TCAR combines a number of basic surgical maneuvers,” Dr. Kumins says. “Together they allow for relatively rapid adoption of this technology. In contrast, transfemoral CAS is considerably more complicated and has a longer learning curve.”

Despite these strengths of TCAR, CEA currently remains the gold standard for patients needing carotid revascularization, and about 90% of patients are eligible for CEA. “That tends to be the first option offered by vascular surgeons unless there’s a compelling reason to do otherwise,” Dr. Kumins notes.

Advertisement

He adds that beyond patients being medically unfit to undergo open surgery, there are several scenarios that argue for a percutaneous strategy, whether TCAR or transfemoral CAS:

When stenting is the favored approach, several patient characteristics may argue for a transfemoral approach over TCAR, such as prior radiation to the neck, tracheostomy, or limited neck access due to severe obesity, neck immobility or similar issues. On the other hand, a patient with highly tortuous vessels may be better suited to TCAR as opposed to transfemoral stenting with an embolic filter. Beyond these situations, both percutaneous options can be considered, with the choice based on relative risk of stroke and other periprocedural complications.

As the field looks toward the prospect of broader coverage of carotid stenting, investigational technologies are proliferating on both the transcarotid and transfemoral fronts.

Cleveland Clinic is participating in ongoing single-arm studies of two such investigational technologies, both involving transfemoral CAS using closed-cell stents. One is assessing the Neuroguard IEP® System, which consists of a nitinol stent, a prepositioned postdilation balloon and an integrated microembolic filter delivered on a single catheter to allow for fewer procedural steps. The other is evaluating the CGuard™ Embolic Prevention System, a double-layer stent comprising an inner open-cell nitinol stent and an outer closed-cell mesh layer.

Advertisement

“The new technologies for carotid stenting are going to multiply,” says Dr. Caputo. “Now that both transcarotid and transfemoral approaches are established modalities, a primary issue to consider is when it’s appropriate to use them in asymptomatic patients, particularly with the availability of new medical therapies.”

Answers to that question, he says, are expected from the ongoing multicenter CREST-2 trial, but results are not anticipated for several years. “One of the most important things we do as vascular surgeons is decide whether or not carotid revascularization is necessary in asymptomatic patients,” Dr. Caputo concludes. “While the proliferation of new approaches and options is very welcome, we need to be judicious in when we apply them.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

JACC review calls for CMS to update coverage decision

Insights from the Cleveland Clinic experience and a multispecialty alliance

Retrospective findings from an executive health program spur interest in broader studies

LLM-driven system uses both structured and unstructured data, provides auditable justifications

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR