Early learnings on use of the minimally invasive alternative to surgical bypass

Soon after the first percutaneous transmural arterial bypass (PTAB) system received FDA approval in June 2023 to treat long-segment, complex femoropopliteal disease, Cleveland Clinic vascular surgeons performed the first commercial implantation of the system in the U.S. Since then, PTAB has begun to leave its mark on the treatment landscape, offering a minimally invasive alternative to open surgical bypass for appropriate patients and showing promise in clinical scenarios extending beyond its initial instructions for use (IFU).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Consult QD caught up with some Cleveland Clinic staff about their experience so far with PTAB technology and how its use may evolve.

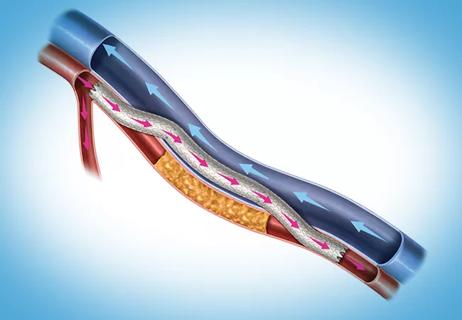

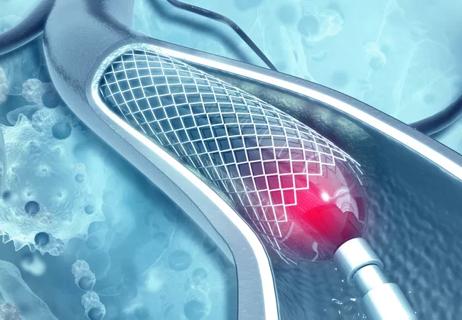

The PTAB system (DETOUR™ System) enables creation of a percutaneous femoropopliteal bypass using standard endovascular techniques, a crossing device and a stent graft. The system’s IFU call for a proceduralist to enter the superficial femoral artery (SFA) origin and use the crossing device to cross into the femoral vein at least 3 cm distal to the origin of the vessel. The device is fed down the femoral vein and reenters the popliteal artery, landing above the tibial plateau in a nondiseased portion of the popliteal artery. Stent grafts are then lined from the distal end to the SFA origin. The figures below illustrate some key stages in the PTAB procedure.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/df4d9b15-971b-4313-8721-c79efd0bef53/peripheral-arterial-bypass-inset1)

Figure 1. Venograms showing how the crossing device is lined up in the vein.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/7f5e5d2c-066c-437e-9df8-279fc111a290/peripheral-arterial-bypass-inset2)

Figure 2. Venogram showing how the vein shares space with the stent graft following deployment.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ef4e2b67-d2eb-4946-867d-5fbfaaf75440/peripheral-arterial-bypass-inset3)

Figure 3. A representative completion image following a PTAB procedure.

“The system allows us to access an area of the popliteal artery behind the knee,” says vascular surgeon J. Eduardo Corso, MD. “We normally don’t perform open bypasses there because the patient would need to be flipped over to gain access. While we usually go either above the knee or below the knee with a prosthetic or vein bypass, with PTAB we can access the popliteal artery further down than the above-knee target and stent all the way down to the knee. The stents perform well in that area, which is a spot where many stents traditionally do not.”

He notes that results in his PTAB cases to date compare favorably to prosthetic bypasses, particularly relative to prosthetic bypasses below the knee, where outcomes beyond a year or two can be poor. “Also, PTAB does not compromise a potential future bypass to a location below the knee,” Dr. Corso says.

Advertisement

Moreover, patients welcome PTAB’s fully percutaneous approach. “Instead of a three- or four-day hospital stay and a 3% to 4% risk of major infection with bypass surgery, patients get an overnight stay or outpatient procedure with PTAB and almost no infection risk,” notes Sean Lyden, MD, Chair of Vascular Surgery at Cleveland Clinic. “When patients learn about PTAB, they’re eager to consider it.”

At the same time, only a fraction of patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) qualify for PTAB based on their disease anatomy. The PTAB system is officially indicated only for patients with long lesions (20-46 cm in length). “That represents only about 10% of the PAD patients we see,” Dr. Lyden says. “The other 90% either have lesions that are too short or have disease that is too extensive for this treatment.”

Additionally, Drs. Lyden and Corso note, PTAB is not appropriate for patients whose popliteal artery is diseased or occluded and for those who have a compromised venous system with small veins.

Dr. Corso says he has successfully performed PTAB in patients who have had previous stenting procedures that have failed and in patients in whom a prior femoral endarterectomy and profundoplasty was insufficient to address their moderate to severe PAD symptoms. “PTAB is a good option for patients with lesions that aren’t easy to treat with a balloon or a stent and for whom open surgical bypass is difficult or too risky, perhaps because of likely poor wound healing,” he says.

The formal indication for PTAB — symptomatic femoropopliteal lesions 20 to 46 cm in length with chronic total occlusion or diffuse stenosis of more than 70% — is based on the patient populations of the DETOUR 1 and 2 clinical trials that supported FDA approval. Pooled two-year data from these trials in 273 patients showed a clinical success rate of 95.3%, primary patency of 69.2%, freedom from target vessel revascularization of 68.1% and freedom from symptomatic deep vein thrombosis of 96.7%.

Advertisement

Dr. Lyden, who serves as a principal investigator of the DETOUR 2 trial, will present three-year results from that study at the VIVA (Vascular InterVentional Advances) 2024 conference in early November.

Meanwhile, in the nearly year and a half since the PTAB system won U.S. regulatory approval, its use in clinical practice has begun to expand a bit beyond its initial trial-based indication.

“The DETOUR trials were very specific about how large the artery had to be where you started the procedure and where you could finish the procedure,” Dr. Lyden says. “But just as for previous treatments in other realms of vascular surgery, operators in the real world look for ways to replicate the anatomic situation from the IFU so they can safely extend the treatment to a broader population.”

Drs. Lyden and Corso have been privy to such extensions of the PTAB procedure via a series of advanced-user forums convened by the PTAB system’s manufacturer. The aim is to exchange operators’ experience with PTAB and lessons from new ways in which some operators are using the procedure. “The forums help maximize learning about the new technology and ensure that no one is working in isolation in these early days,” Dr. Lyden says.

During the forums, he adds, Cleveland Clinic advocates for a measured, iterative approach to expanding how PTAB is used. “We feel the best way to do this is to take small steps outside the boundary conditions and to ensure reproducibility of results before proceeding further,” he says, citing three examples undertaken by Cleveland Clinic to date:

Advertisement

These extensions of the IFU have yielded outcomes consistent with those in the pivotal DETOUR trials both at Cleveland Clinic and elsewhere, Dr. Lyden reports.

He says the advanced-user forums allow early adopters of PTAB to pool their experience with small innovations they have each tried on their own, with plans to start collecting data and potentially publish their collective experience.

Meanwhile, the manufacturer of the PTAB system has started a postmarket registry to capture outcomes of all the system’s uses in clinical practice. Cleveland Clinic is participating in the registry, which is part of the Society for Vascular Surgery’s Vascular Quality Initiative.

“We are very supportive of this registry as an effort to accurately understand real-world use of PTAB,” Dr. Lyden says. “It’s an ideal way to both ensure safety and efficacy for the system’s established indications and to guide and refine potential innovations in its use.”

“PTAB offers reduced hospital stays and reduced infection risk for patients with complex PAD,” adds Aravinda Nanjundappa, MBBS, MD, a Cleveland Clinic interventional cardiologist and vascular medicine specialist. “While PTAB is currently indicated for lesion lengths of 20 to 46 cm, it has shown promise in treating failed prior interventions and patients unsuitable for traditional bypass, and this ongoing data collection is likely to gradually expand its application to more patients.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Larger data set confirms safety, efficacy and durability for SFA lesions over 20 cm

3 specialists share multidisciplinary perspectives on a widely impactful cardiovascular condition

Two cardiac surgeons explain Cleveland Clinic’s philosophy of maximizing arterial graft use

Study finds that in the absence of ACS, the yield is low and outcomes are unaffected

Benefits of new FDA safety determination go beyond expanding patients’ options

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR