Nimble multidisciplinary planning paves a path to infant’s heart transplant

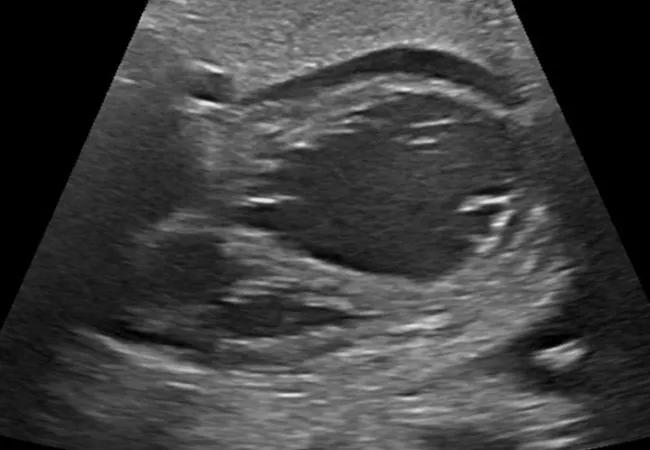

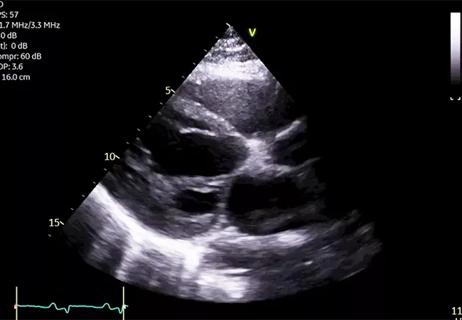

Obstetricians at a local hospital referred a pregnant woman to Cleveland Clinic Children’s Fetal Care Center late in her third trimester when a routine fetal echocardiogram revealed potentially serious cardiac anomalies. A repeat scan conducted upon her arrival revealed severe left ventricular dilation (Figure 1), poor function with no anterograde flow across the aortic valve, and severe mitral valve regurgitation. The differential diagnosis was left ventricular aneurysm or dilated cardiomyopathy.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Figure 1. Fetal echo showing severe left ventricular dilation.

“Our concern was that there was a high likelihood the baby would not survive outside the womb after birth, because the left ventricle could not pump oxygenated blood to the body,” explains pediatric and congenital heart surgeon Alistair Phillips, MD, who viewed the scan with Samir Latifi, MD, Chair of Pediatric and Critical Care Medicine, and pediatric cardiologist Thomas Fagan, MD. “Nor could we arrange for blood to get to the right ventricle to be pumped to the lungs and body, which is something we do for patients born with hypoplastic left heart syndrome.”

Given the severity of the findings, a multidisciplinary team was assembled to discuss treatment options, consisting of more than 30 physicians and nurses from pediatric and maternal anesthesiology, pediatric cardiac anesthesiology, maternal-fetal medicine, obstetrics, congenital heart surgery, fetal surgery, neonatology, palliative care, pediatric cardiology and heart failure, along with perfusionists and nursing leadership. Ultimately, two options were presented to the family:

Advertisement

The family opted for the ExIT procedure, but the mother went into labor the day the C-section was scheduled, which precluded the ExIT plan. Fortunately, the healthcare teams had prepared in advance for both options.

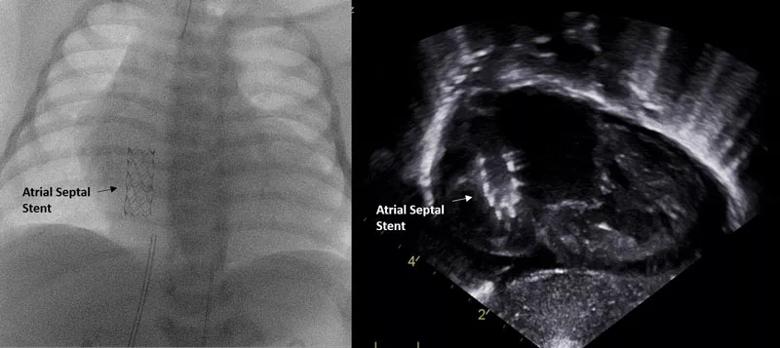

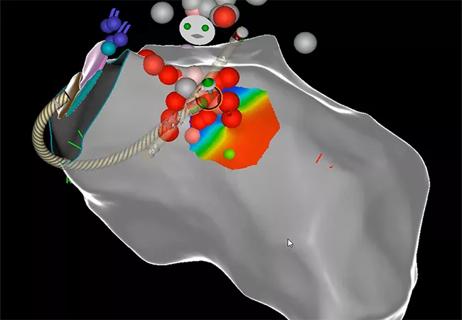

Preparation for the immediate catheterization and atrial septal stent placement involved hours of planning and team rehearsals. Essential personnel — including cardiologists, pediatric cardiac anesthesiologists, neonatologists and cath lab personnel — were assigned roles, and walk-throughs were conducted. “This was important because any wasted minute, even second, between the baby’s delivery and stenting the atrial septum could result in a very poor outcome,” says Dr. Fagan.

Rehearsing made all individuals aware of their role, their position in the room and the timing of their involvement. “This helped everyone know where to stand, so they would not be in each other’s way,” says Dr. Latifi.

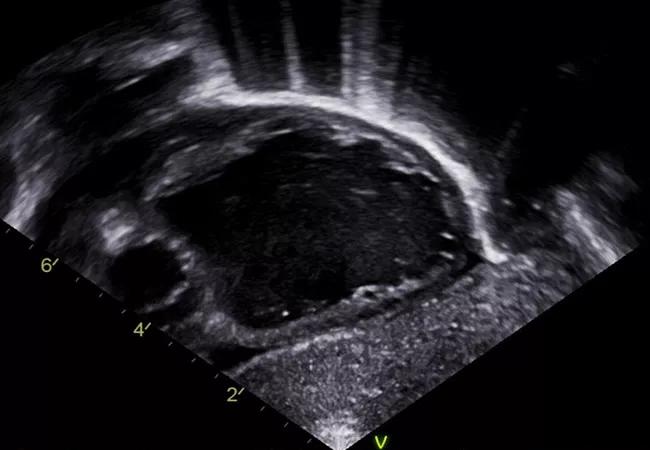

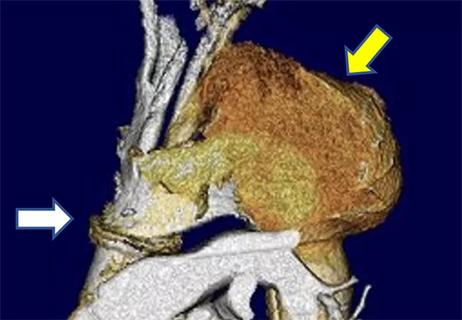

A baby boy was delivered in the Special Delivery Unit and immediately transferred to the adjacent cardiac cath lab. He initially appeared vigorous but turned limp and bradycardic in the cath lab shortly after arrival. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation was started within 20 seconds. The neonatologists placed umbilical lines and started an IV alprostadil drip. Fluoroscopy and echo (Figure 2) confirmed the prenatal findings. Dr. Fagan obtained femoral venous access and successfully placed a stent to open the atrial septum (Figure 3). The infant immediately improved and was transferred to the pediatric cardiac ICU for further care. The time from delivery to stent placement was less than 25 minutes.

Advertisement

Figure 2. Confirmatory echo taken in the cardiac cath lab immediately after birth.

Figure 3. Angiogram and echo taken after atrial septal stent placement.

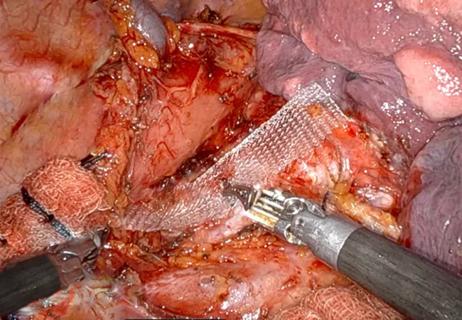

The baby remained stable in the ICU but could not be weaned off the ventilator due to poor left ventricular function. Therefore he received a 10-mL Berlin Heart EXCOR® VAD and had the stent in his atrial septum removed and the hole closed. His recovery was unremarkable, and he was extubated on postoperative day 2 and transferred to a regular hospital floor.

Three months later, in April 2019, he underwent heart transplantation. He continues to be monitored regularly and has fared remarkably well. “He is growing and acting normally and has shown no tendency to reject the new organ,” says Gerard J. Boyle, MD, Medical Director of Pediatric Heart Failure and Transplant Services, who continues as the boy’s pediatric cardiologist.

“There is no clear consensus on the management of neonatal dilated cardiomyopathy,” says Dr. Latifi. He and his colleagues note that the timing of the mother’s referral in this case — three weeks prior to her delivery date — was not early enough to facilitate ideal management.

“Early diagnosis and referral to a fetal care center allows for sufficient time to prepare the family, review treatment options and develop a treatment plan,” Dr. Phillips observes.

There can never be too much preparation involved in developing and carrying out a treatment plan for a complicated case like this, adds Dr. Boyle. “We prepared for just about every possibility,” he says.

Advertisement

“Having the multidisciplinary team plan for all possible situations with attention to every detail is crucial for optimal outcomes in newborns with complex cardiac disease,” notes Dr. Fagan.

Also critical was having Cleveland Clinic’s distinctive Special Delivery Unit just a few yards away from the cath lab. “This allowed transfer of the newborn to the cath lab within minutes, in contrast to potentially hours for deliveries outside of a children’s hospital or in the absence of such a unit,” says Hani Najm, MD, Cleveland Clinic’s Chair of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery.

“Typically a newborn like this would have succumbed almost immediately after birth,” Dr. Najm adds. “But the outlook for these babies is changed at a center of excellence with expertise in managing neonates with lesions like this as well as their mothers. The hallmark of success is an integrated care process that starts with the obstetrician followed by multiple specialists such as the fetal cardiologist, interventional cardiologist, heart failure cardiologist, cardiac surgeon and intensivist — in addition to other teams.”

Dr. Phillips concurs: “Caring for such complex patients requires a dedicated multispecialty team that works exceptionally well together, communicates well and remains nimble.”

Dr. Latifi points out that the family should be considered a critical part of the team. “Educating multiple family members about medications, complications and care protocols takes the burden off parents and physicians and relieves everyone’s anxiety,” he says.

Advertisement

“By working as a multidisciplinary team that included the family, we were able to deliver this family a healthy child,” Dr. Boyle concludes.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic-pioneered repair technique restores a 61-year-old to energetic activity

Excessive dynamic airway collapse presenting as dyspnea and exercise intolerance in a 67-year-old

Young man saved multiple times by rapid collaborative response

Necessity breeds innovation when patient doesn’t qualify for standard treatment or trials

After optimized medical and device therapy, is there a role for endocardial-epicardial VT ablation?

Fever and aortic root bleeding two decades post-Ross procedure

How to time the interventions, and how to manage anesthesia risks?

A potentially definitive repair in a young woman with multiple prior surgeries