What to look for and when to use immunosuppressive medications

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/0e0be8f7-3773-4a40-afdd-fde312f6287d/21-RHE-2057219-Hajj-Ali_NoninfectiousAutoimmuneScleritis-CQD_650x450_jpg)

Nodular anterior scleritis in a patient with Behcet’s disease

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 57-year-old patient you have been treating for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) presents for a scheduled follow-up with complaints of eye pain that have gradually increased over two weeks. The pain is sharp and sometimes wakes her up at night. She reports sensitivity to light and indicates that she isn’t seeing as well as she used to. On exam, the patient has bilateral redness in her eyes. What’s your next move?

A 68-year-old patient has been referred to you by ophthalmology for workup to identify possible systemic associations with newly diagnosed scleritis. Your colleague in ophthalmology has ruled out infection and malignancy as sources of the inflammatory ocular disease, and is looking for other potential causes. The patient recounts her history of sudden onset, severe pain in both eyes. She has no history of sinus problems, no joint pains, no rashes, no weight loss, no neuropathy symptoms, no gastrointestinal or pulmonary symptoms. What tests do you order?

Treating inflammatory ocular disease is of utmost importance to prevent blindness and complications of systemic rheumatic disease, when present. Scleritis, or inflammation of the sclera, is a rare condition with an incidence of 3.4-4.1 per 100,000 person years. Nearly 36% to 44% of scleritis cases are associated with systemic conditions, most often rheumatoid arthritis (RA); other systemic diseases include granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), relapsing polychondritis (RP), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), lupus erythematosus and sarcoidosis. Importantly, scleritis can be a severe manifestation of rheumatic disease that can result in blindness.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3eae6607-edfb-4b00-9b1f-e04a68de5a2d/scleritis-images-1024x1024_png)

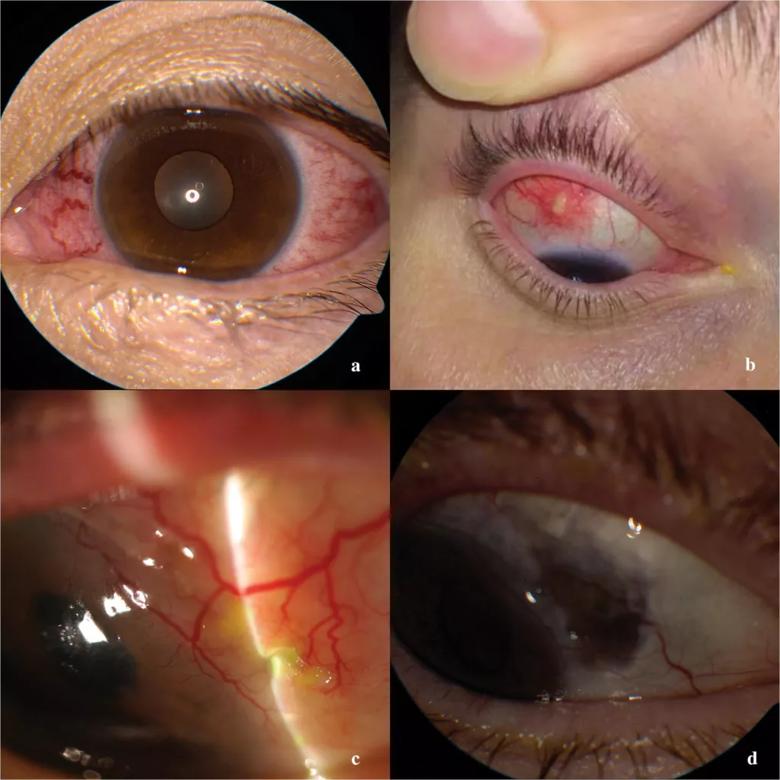

Caption: a. Patient with relapsing polychondritis and diffuse anterior scleritis. b Nodular anterior scleritis in a patient with Behcet’s disease. c. Necrotizing scleritis (note area of thinning). d Same patient with necrotizing scleritis, posttreatment. See area of purple discoloration, due to thinning of sclera and exposure of underlying choroid (uveal) layer.

Rheumatologists may encounter patients with symptoms of scleritis as part of ongoing care for patients with systemic conditions, or as a referral from ophthalmology for workup of systemic associations and assistance with immunosuppression.

When assessing a patient for “red-eye” with severe ocular pain, rheumatologists should have a high index of suspicion for scleritis. If you have already diagnosed your patient with an autoimmune disease (as in the first case vignette), prompt ophthalmic assessment is warranted.

If the patient has been referred to you by ophthalmology (as in the second case vignette), a review of symptoms should be conducted, noting the presence or absence of sinus disease (which might indicate GPA or sarcoidosis) as well as orogenital ulcers (IBD or Behcet’s syndrome), shortness of breath (sarcoidosis), neuropathy and rashes (GPA or sarcoidosis), and a history of joint pain (RA or inflammatory arthritis).

Tests to consider include complete blood count, acute phase reactants, creatinine, antIneutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) and urinalysis. In patients with olgio- or polyarthritis or recent onset polyarthralgia, consider testing for rheumatoid factor and anticitrullinated peptide antibody. If the review of systems or other laboratory results suggest systemic lupus erythematosus, antinuclear antibody should be performed. When ocular or systems findings suggest sarcoidosis or GPA, pursue CT of the chest. Very rarely ANCA will return positive in patients with scleritis without any systemic symptoms. Many of these patients, when followed, will develop systemic GPA. Given the systemic nature and the involvement of vital organs of ANCA-associated vasculitis, we recommend testing all patients with scleritis for ANCA.

Advertisement

In scleritis, the treatment goal is to alleviate pain and prevent complications, which are most common in patients with necrotizing and posterior scleritis. Ocular complications include peripheral ulcerative keratitis, vision loss or ocular perforation.

Treatment of scleritis depends on the severity and associated systemic disease. NSAIDs are the first line therapy for anterior non-necrotizing scleritis. Conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) (e.g., methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate); biologic therapy, such as anti-TNF drugs (e.g., rituximab, infliximab, tocilizumab); and alkylating agents (e.g., cyclophosphamide) have all been used in refractory disease in addition to glucocorticoids. If there is a risk of perforation, cyclophosphamide is usually the choice of therapy. The American Uveitis Society recommends the anti-TNF agents in ocular inflammatory conditions as second-line corticosteroid-sparing therapy for chronic and severe scleritis, especially in diseases with evidence of efficacy of these medications such as rheumatoid arthritis, Behcet’s syndrome and IBD. There are limited data on the effectiveness on csDMARDs in scleritis, and randomized control trials comparing DMARDs for the treatment of noninfectious scleritis are needed.

Comanagement and effective communication between rheumatology and ophthalmology is extremely important to optimize better outcomes. Rheumatologists are key players in the treatment and follow-up in these patients, even in the absence of systemic disease for two reasons:

Advertisement

In conclusion, the rheumatologist plays a major role in managing the therapy of patients with scleritis. It can be challenging to familiarize yourself with diseases that you are unable to fully assess with the tools you have available in your rheumatology clinic and rely on other specialties. Effective communication with your ophthalmology colleagues is crucial in the care of these patients.

Our practice at Cleveland Clinic is designed to facilitate interconnectedness of rheumatology and other specialties. That said, we recognize that this may not be the case for our rheumatology colleagues in other practices and have empathy for the sorts of time commitments that may require deliberation among two or more specialties. Methods to facilitate interdisciplinary communication with ophthalmologists include interdisciplinary clinics and case conferences. This will improve the welfare of our patients, which our most important goal in medicine.

*Please note: Images used with permission. Originally published in Nevares A, Raut R, Libman B, Hajj-Ali R. Non-infectious Autoimmune Scleritis: Recognition, Systemic Associations, and Therapy. Curr Rheum Rep. 2020 Mar 26;22(4):11.

Advertisement

Advertisement

A review of pathophysiology, risk factors, clinical presentation and treatment options

How computational tools and personalized biomechanics can improve keratoconus detection, ectasia risk assessment and surgical outcomes

Motion-tracking Brillouin microscopy pinpoints corneal weakness in the anterior stroma

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Prescribing eye drops is complicated by unknown risk of fetotoxicity and lack of clinical evidence

A look at emerging technology shaping retina surgery

A primer on MIGS methods and devices

7 keys to success for comprehensive ophthalmologists