Findings hold implications for screening and potential nonsurgical therapy

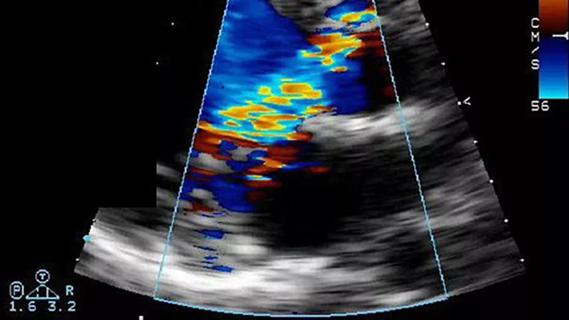

TMAO, a metabolite produced by gut bacteria, has already been linked to heart attack, stroke and other cardiometabolic diseases. Now a new study shows that it also increases risk for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA).

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The findings, published in Circulation (2023;147:1079-1096) by a multicenter team including Cleveland Clinic researchers, are significant for two reasons: they suggest that (1) TMAO testing could be used as a screening tool for AAA and (2) blocking TMAO could offer a first-ever nonsurgical treatment option for the condition.

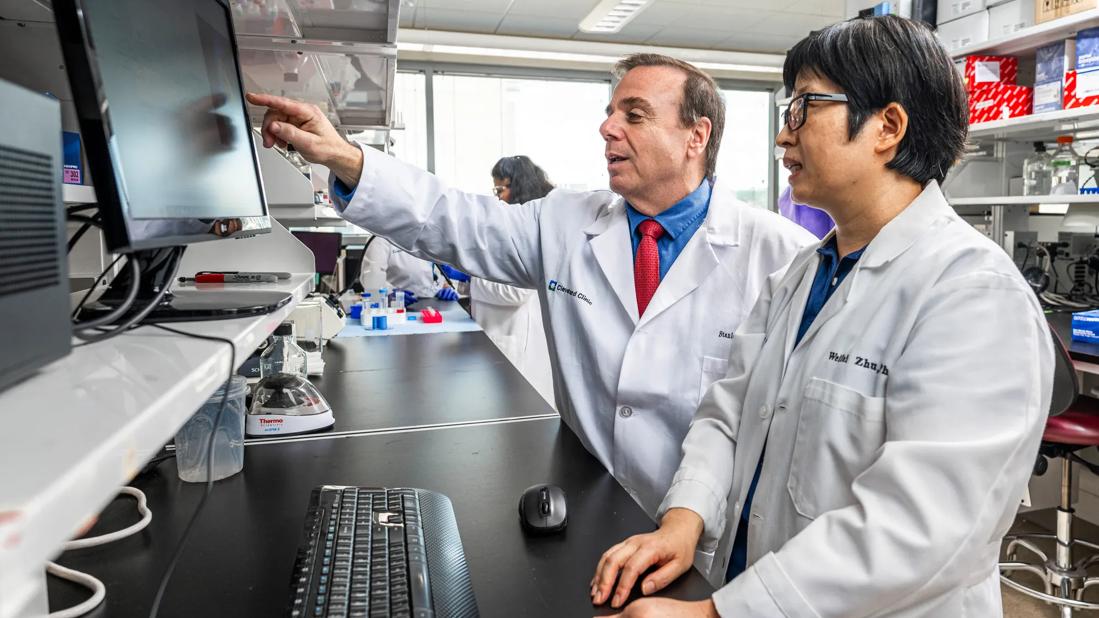

“Aortic aneurysm is a horrible silent killer, and we currently have no therapies for it except surgery,” says co-investigator Stanley Hazen, MD, PhD, Chair of the Department of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Sciences in Cleveland Clinic’s Lerner Research Institute. “Most people don’t present until they have an aortic dissection, at which point a significant number of patients don’t survive. This paper argues that a therapy might be developed to target this pathway and halt the progression of aneurysm growth, so it’s highly exciting for that reason.”

TMAO (trimethylamine N-oxide) is a metabolite that’s produced when gut bacteria digest choline, carnitine and lecithin — nutrients that are most abundant in red meat and other animal products. Previous research by Dr. Hazen and colleagues has shown direct mechanistic links between high levels of TMAO and cardiometabolic diseases including atherosclerosis, thrombosis and chronic kidney disease.

Study co-investigator Scott Cameron, MD, PhD, says that looking at connections between TMAO and AAA just made sense, since atherosclerosis is the leading pathogenic driver of AAA and TMAO elevation is fairly established in many patients with atherosclerosis. He adds, however, that the connection turned out to be even stronger than he expected. “I was quite surprised by how striking the data were,” says Dr. Cameron, Section Head of Vascular Medicine at Cleveland Clinic.

Advertisement

The research team — led by corresponding author Phillip Owens, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine — first studied plasma samples taken from two independent cohorts numbering more than 2,100 patients. They found that higher levels of TMAO were indeed associated with increased incidence of AAA and with aneurysm growth.

They then conducted animal studies to better understand the connection. First they found that increasing TMAO levels in mouse models of AAA caused the animals’ aneurysms to grow faster. They then gave the mice a drug that blocks TMAO synthesis, fluoromethylcholine, and found that it stopped aneurysm development. Finally, they simultaneously inhibited TMAO synthesis in mice and introduced TMAO directly in drinking water; this caused aneurysms to grow again.

Dr. Hazen says the collective results are compelling. “There’s ample data arguing that TMAO is contributing to aneurysm development in multiple different animal models, and the human data all supports this,” he notes.

An additional mechanistic study showed that a stress sensor protein called PERK (protein kinase R-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase), which is involved in correcting misfolded proteins, plays a key role in the process.

Drs. Hazen and Cameron stress that their study shows the potential for major new tools in diagnosing and treating AAA.

“We have no medical therapies to treat aneurysm right now that are particularly effective, and we have no blood tests to predict who is going to have an aneurysm and who will do well,” Dr. Cameron observes.

Advertisement

The study supports the need for more facilities to offer TMAO testing, he adds. For patients who do show elevated levels of TMAO, providers should consider additional imaging tests to screen for AAA.

The study also suggests a possible new treatment, Dr. Hazen says. His lab developed the tool drug fluoromethylcholine used in the present studies, and his lab has developed additional drugs that are being evaluated to block TMAO formation in humans.

“This adds to the list of potential conditions that a TMAO-blocking agent could treat,” he says, “whether it be atherosclerosis, thrombosis, heart failure, chronic kidney disease — and now aneurysm expansion and growth.”

He notes that his team will continue to work on follow-up studies.

Beyond the clinical implications, Dr. Hazen says the study is yet another example of the surprising connections between the gut microbiome and other systems within the body. He adds that it also represents a new frontier in medicine: manipulation of microbes — not by killing them with antibiotics, but by drugging them.

“Gut microbes are linked to our health in so many different ways that we never would have expected,” he concludes. “In this case they are making a metabolite that’s causing aneurysm growth in the host. How cool is that?”

Advertisement

Advertisement

New Cleveland Clinic data challenge traditional size thresholds for surgical intervention

Study finds comparable midterm safety outcomes, suggesting anatomy and surgeon preference should drive choice

New review distills insights and best practices from a high-volume center

Blood test can identify patients who need more frequent monitoring or earlier surgery to prevent dissection or rupture

Recent Cleveland Clinic experience reveals hundreds of cases with anatomic constraints to FEVAR

Multicenter pivotal study may lead to first endovascular treatment for the ascending aorta

Residual AR related to severe preoperative AR increases risk of progression, need for reoperation

Large cohort study finds significant effect in men and nonsmokers