Nearly three-quarters found lacking in methodological quality and/or reporting practices

The synthesis and reporting of systematic reviews in top-tier cardiology journals has been marked by serious and widespread quality gaps over the past decade, concludes an analysis from a Cleveland Clinic led-research team published in Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine (2021;8:671569). The study found that over 70% of such reviews ranked as low or critically low in quality on the AMSTAR tool for assessing the quality of systematic reviews.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Systematic reviews have long resided at the top of the evidence-based pyramid and are increasingly relied on to shape clinical practice guidelines in cardiology and other specialties,” says the study’s lead author, Abdelrahman Abushouk, MD, a research fellow in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Cardiovascular Medicine. “Our findings demonstrate a need for greater rigor in conducting, reporting and publishing of such reviews to make sure they are fulfilling their intended purposes and meeting the quality standards needed to inform healthcare decisions.”

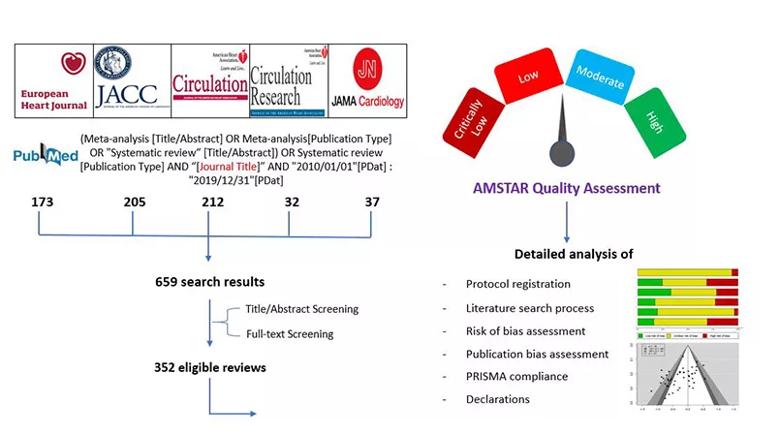

The researchers searched PubMed to identify all systematic reviews (with or without meta-analyses) published from 2010 to 2019 in the five cardiology journals with the highest impact factor: Circulation, European Heart Journal, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Circulation Research and JAMA Cardiology.

They then extracted data on eligibility criteria, methodological details, assessments of bias and sources of funding. Reviews were also evaluated using the AMSTAR (Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews) tool, which scores review quality as either high, moderate, low or critically low. Figure 1 summarizes the study methodology.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/68e9749c-f074-4814-ac94-e8d77b34cbe2/21-HVI-2232209-Inset1-805x450-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Schematic summary of the study methodology.

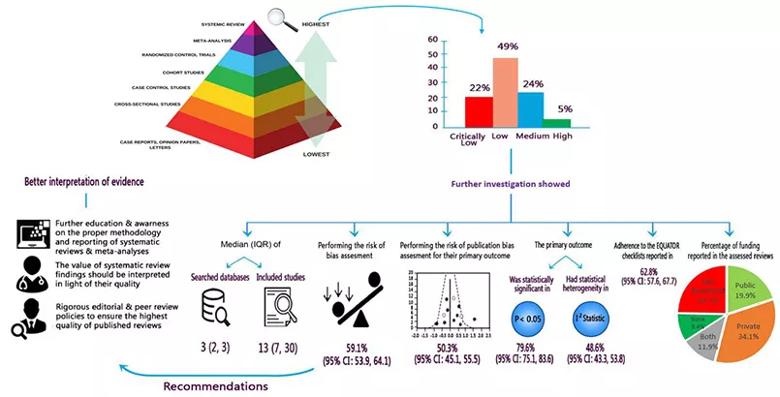

A total of 352 eligible systematic reviews were identified, with the number of published reviews per year growing considerably over the study period. Analysis of these 352 reviews revealed the following key findings:

Advertisement

Figure 2 summarizes additional results and recommendations from the researchers.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/830ee23e-903e-4397-9663-ac0f43ff8838/21-HVI-2232209-Inset2-805x410-1_jpg)

Figure 2. Schematic summary of findings and implications for researchers, clinicians and stakeholders. Reprinted from Abushouk et al., Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine (2021;8:671569). © The authors.

“This analysis uncovers some serious shortcomings of systematic reviews in the cardiology literature,” says Dr. Abushouk. “The low or critically low AMSTAR quality scores received by almost three-quarters of assessed reviews resulted from incomplete or absent reporting of several essential steps in the systematic review process, such as protocol registration, assessment for risk of bias and assessment for publication bias.”

“Publication bias is a particularly prevalent problem in the biomedical literature that favors studies with positive findings,” adds study co-author Rishi Puri, MD, PhD, of Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Cardiovascular Medicine. “Evaluating for the risk of publication bias is a must in order to get the full picture from a systematic review of a given clinical question. If not all relevant studies are included, we cannot have confidence in the reliability of the review’s conclusions.”

The authors conclude their study report with a number of recommendations for closing the quality gaps identified. They note that guidelines on the proper conduct and reporting of systematic reviews — such as the PRISMA statement (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions — have been available for years but are not adequately followed. Improving adherence to these guidelines, the authors argue, will require a collaborative effort among researchers, journal editorial boards and policymakers.

Advertisement

The authors also note one encouraging finding of their analysis: publication year was positively associated with an improving AMSTAR quality score. “This association was small, and it requires further confirmation, but it suggests that expertise in good systematic review methodology may be slowly increasing among authors and reviewers,” says co-author Grant Reed, MD, of Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Cardiovascular Medicine. “We hope this analysis will help further advance any such trend.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Multimodal evaluations reveal more anatomic details to inform treatment

Insights on ex vivo lung perfusion, dual-organ transplant, cardiac comorbidities and more