Two cases show multiple factors to consider

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3f9dc126-cfd5-4654-a608-0af61c3647bf/shoulder-pain-1156927023)

Shoulder pain

By Jason C. Ho, MD; Eric T. Ricchetti, MD; and Vahid Entezari, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

It is estimated that by 2025, more than 300,000 shoulder replacements will be done annually in the U.S. The number of complications associated with these surgeries likely will increase as well. With the growing number of replacements in an aging and increasingly active population, falls and fractures around prosthetic implants will become more common.

Often we can treat these fractures without surgery, in a brace with simple therapy. However, there are times when the fracture and functionality of a patient make surgical management the preferred treatment. When this is the case, it becomes a complex, shared decision on whether to proceed with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) vs. revision arthroplasty due to the patient’s functionality, medical risks, physiology and fracture pattern.

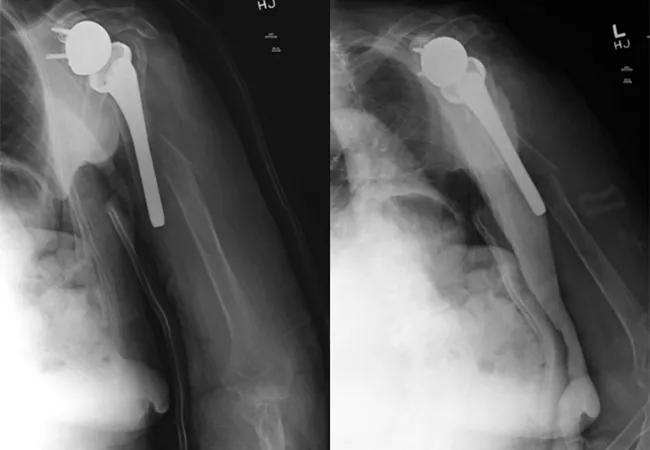

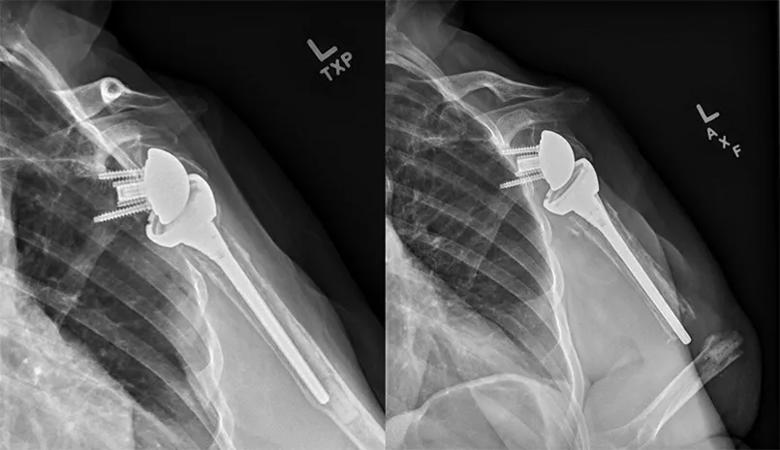

An 84-year-old right-hand-dominant female fell onto her left arm from a standing height four days prior to presentation. She lived at home with her family and used a walker for ambulation doing basic activities of daily living. She went to the local emergency room and was diagnosed with a left periprosthetic humerus fracture around a reverse total shoulder replacement done more than five years earlier for rotator cuff tear arthropathy (Figure 1). Prior to the fall, she had shoulder-level function with her reverse replacement and no complications or difficulties. Her exam in the office showed intact motor function. Her axillary nerve and deltoid appeared to be functioning, and her prior deltopectoral incision was well healed. Surgical intervention was discussed due to the displacement and comminution of the fracture.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5ebd8a7f-31b1-496d-91aa-cee760ee1b53/21-ORI-2285515-650x450-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Injury films showing comminuted periprosthetic humerus fracture around a reverse shoulder replacement stem.

We discussed ORIF vs. revision reverse replacement to a megaprosthesis due to the poor bone stock and concern for a loose implant. With her functional status, the preference was to perform an ORIF to preserve any tuberosity and soft-tissue attachments and prevent postoperative instability. Our concern with a revision reverse replacement was potential perioperative complication risk, specifically instability in the setting of a patient with frequent falls and walker use. We also discussed nonoperative management in the form of a Sarmiento brace, but due to the displacement and comminution around the implant, and possible loose prosthesis, we did not feel this was a viable option as it likely would lead to nonunion and an inability to use that arm for ambulating with a walker. After discussing these risks and benefits with the patient and her family, we elected to proceed with ORIF with a backup plan of revision to a megaprosthesis.

At the time of surgery, we used an extended deltopectoral incision to expose the fracture. Intraoperatively, the stem was noted to be well fixed to the proximal metaphyseal bone but loose at the tip of the stem. With good proximal bone fixation, it was decided to pursue an ORIF with a long proximal humeral locking plate. We pieced together the comminuted fracture from the intact distal shaft segment to the proximal bone around the prosthesis.

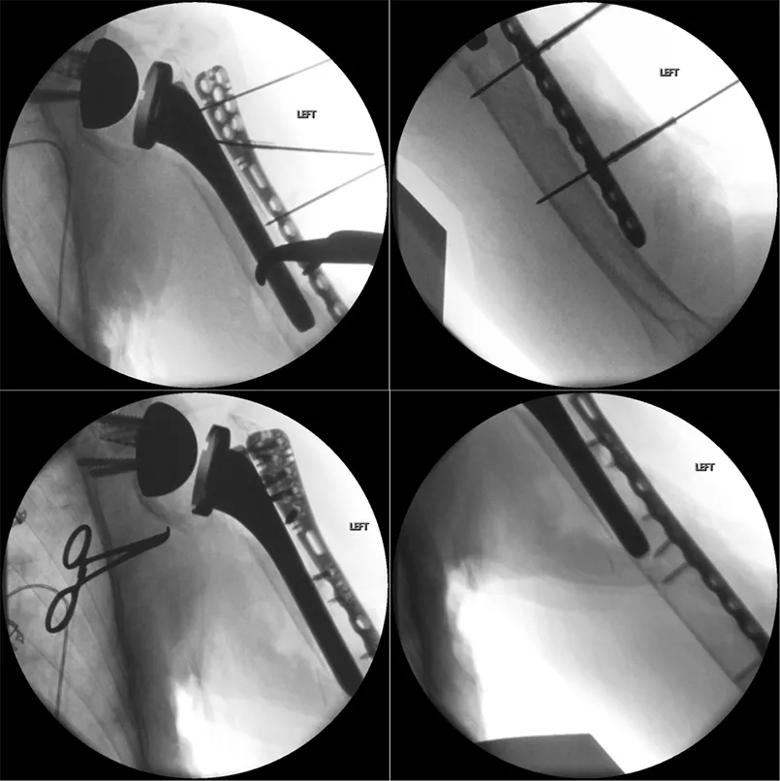

There also appeared to be a more chronic fracture in the proximal humerus that was healing in addition to the acute fracture around the tip of the stem. We used a unique fracture plate that allowed for variable-angle screw placement around the implant to provide compression of the plate, and then locking caps to create fixed-angle locking screws (Figure 2).

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2ad82224-e5ac-4588-9b71-cf3644779538/21-ORI-2285515-Inset2_jpg)

Figure 2. Intraoperative fluoroscopic views showing provisional reduction with clamps and wires from the plate, and final plate fixation prior to allograft placement.

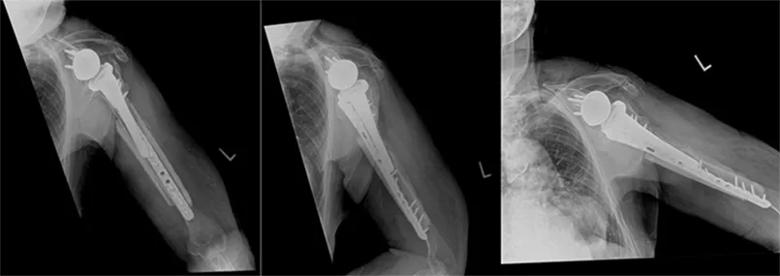

Due to the poor bone stock, we elected to place strut grafts anterior and posterior to the plate as reinforcement of the construct. A femoral strut allograft was fashioned into two long cortical pieces measuring 16 cm posteriorly and about 12 cm anteriorly that were fixed with multiple cerclage tape sutures around strut grafts and the plate.

Before final tensioning of the cerclage sutures, we placed a mixture of cancellous allograft chips with demineralized bone matrix around the fracture site and struts to help with healing of the allograft (Figure 3).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c24eb272-d66b-4329-8ea6-41b8f702a1ea/21-ORI-2285515-Inset3_jpg)

Figure 3. Intraoperative photo demonstrating the plate placement with allograft strut grafts on either side held in place by cerclage sutures, and postoperative recovery room X-rays of the construct.

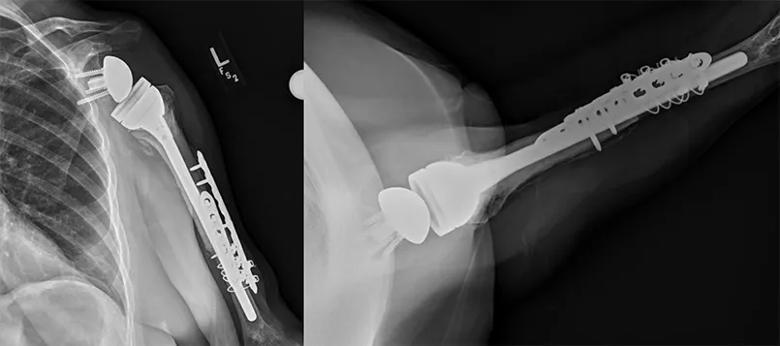

At 12 weeks postop, the patient was using the arm without much difficulty. She had a difficult time with restrictions early on as anticipated and had some postoperative swelling that was resolving slowly. However, she was starting to use her arm as she did before her fall without complaint. The radiographs showed strut grafts intact, healing of the fracture and no migration of the hardware (Figure 4).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/064152fe-c59c-4afd-bd75-65e1fa52db8a/21-ORI-2285515-Inset4_jpg)

Figure 4. Three-month postoperative X-rays demonstrating maintained reduction of the fracture and construct without implant failure.

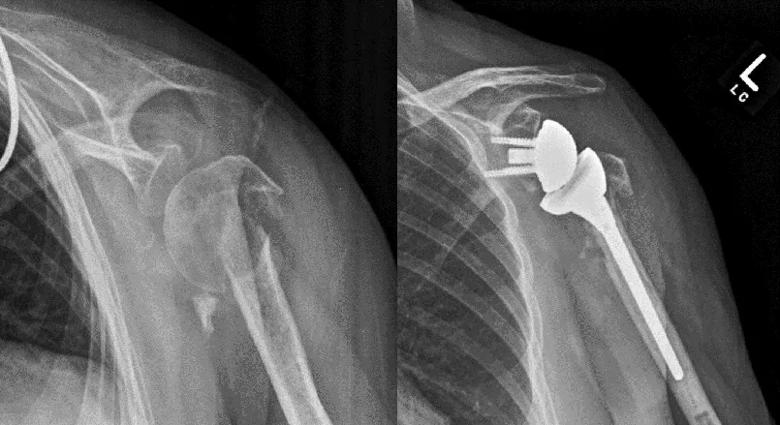

A 60-year-old right-hand-dominant female pack-per-day smoker initially presented with a proximal humerus fracture nonunion that was treated with a reverse shoulder replacement with tuberosity repair in 2013 (Figure 5). She did well with excellent overhead function until presenting 6.5 years after surgery with atraumatic new-onset pain after a period of gradually worsening arm pain. Swelling and deformity of the arm with ecchymosis was seen without neurovascular compromise. X-rays showed a periprosthetic fracture at the tip of the stem with signs of humeral component loosening (Figure 6).

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/915fcf59-7b62-4501-b22a-d90189754009/21-ORI-2285515-Inset5_jpg)

Figure 5. Initial X-rays showing proximal humerus fracture nonunion and early follow-up after successful reverse shoulder replacement.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/9e71343a-6d45-4b5f-ad92-b8ef57119fdc/21-ORI-2285515-Inset6_jpg)

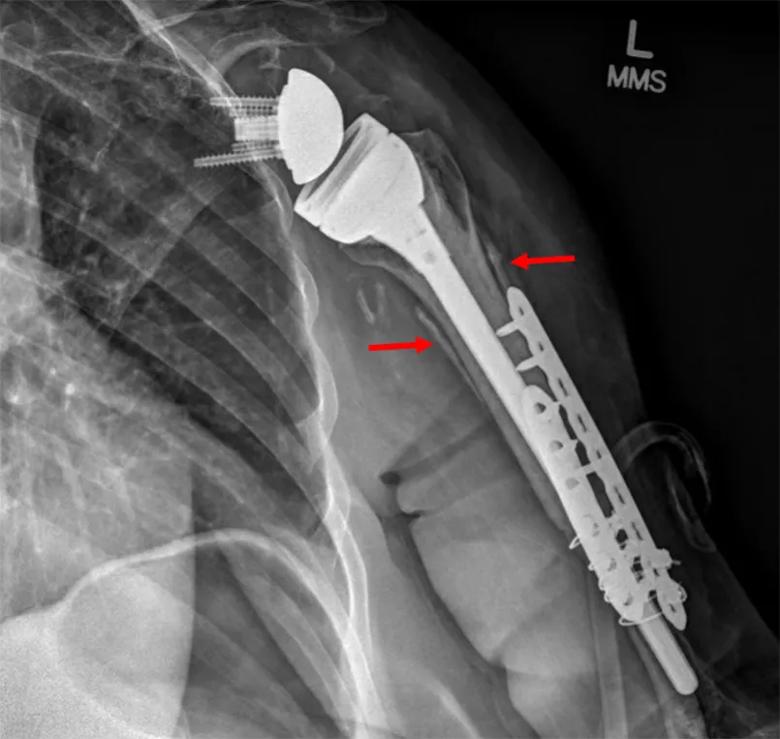

Figure 6. Postoperative X-rays at five and 6.5 years, demonstrating humeral component loosening and eventual periprosthetic fracture.

Because of the young age of the patient with her previously excellent function, and significant fracture displacement, surgical intervention was discussed, specifically revision arthroplasty with an allograft-prosthetic composite (APC) construct vs. ORIF based on the proximal humeral bone stock at surgery.

At the time of surgery, an ORIF was initially attempted, but the proximal bone stock was noted to be too poor for stable fixation. Revision reverse shoulder arthroplasty with APC was performed. The shell of proximal humeral bone was kept in place to preserve soft-tissue attachments for stability. The new long-stem implant was cemented into the allograft proximal humerus and native distal humeral bone.

Two plates were placed to reinforce the APC-native humeral interface, and cerclage wires were used to gain additional fixation distally. The remaining rotator cuff tissue was repaired to the rotator cuff attachments of the proximal humeral allograft, and the native proximal bone was clamshelled around the APC proximally and held by cerclage sutures (Figure 7).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a515d8a0-1866-451d-85a8-fbf2b06507ac/21-ORI-2285515-Inset7_jpg)

Figure 7. Early postoperative X-ray demonstrating the APC construct with red arrows indicating the clam-shelled native bone around the APC construct.

Cultures taken at the time of surgery were negative for infection. At the one-year follow-up visit, the patient had excellent function, with active forward elevation to 120 degrees, external rotation to 40 degrees and internal rotation to the lower thoracic spine (Figure 8).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/16ed4cab-7f22-4dd4-ae44-14a7753df6bb/21-ORI-2285515-Inset8_jpg)

Figure 8. One-year postoperative X-ray demonstrating intact APC without failure of construct and hardware.

These two cases illustrate the complex decision-making required when surgically treating periprosthetic humerus fractures. A team approach, involving multiple fellowship-trained shoulder surgeons as well as other specialists throughout and outside of orthopaedic surgery, is the best way to identify optimal surgical technique.

Advertisement

Jason C. Ho, MD, and Vahid Entezari, MD, are associate staff in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Cleveland Clinic. Eric T. Ricchetti, MD, is the Director of Cleveland Clinic Shoulder Center as well as The Maynard Madden Arthritis Chair and Professorship in Medicine. All three physicians are fellowship-trained in shoulder and elbow surgery.

Advertisement

How it’s similar but different from the direct anterior approach

Collaboration must cross borders and disciplines

Systematic review of MOON cohorts demonstrates a need for sex-specific rehab protocols

Should surgeons forgo posterior and lateral approaches?

How chiropractors can reduce unnecessary imaging, lower costs and ease the burden on primary care clinicians

Why shifting away from delayed repairs in high-risk athletes could prevent long-term instability and improve outcomes

Multidisciplinary care can make arthroplasty a safe option even for patients with low ejection fraction

Percutaneous stabilization can increase mobility without disrupting cancer treatment