Addressing the brain-body interplay can help patients achieve better outcomes

Chronic pelvic pain (CPP) shares many of the challenges that accompany any refractory pain: potential interference with function, a complex interplay between biological and psychological factors, and exacerbation of distress when relief efforts fail. Women with CPP also often suffer one additional symptom: isolation arising from limited understanding of pelvic floor disorders in broader society and from the difficulty of discussing intimate body parts.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“If you’re on an elevator and someone asks, ‘How are you?’ you’re not very likely to say you’re having a lot of vulvar pain,” says clinical psychologist Anna Gernand, PsyD. “And isolation is one of the psychosocial factors involved in pain processing. When it feels like nobody understands what you're going through, and you're carrying something that can be incredibly heavy — physically and emotionally — on your own, the body can respond defensively. Stress hormones, inflammation, muscle tension, and a nervous system on high alert can intensify pain, compounding distress in a vicious cycle.”

Dr. Gernand practices pelvic pain psychology in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Subspecialty Care for Women, where treatment of pelvic floor disorders emphasizes a whole-person approach. Although pelvic pain psychology is still a relatively new focus of practice, research and clinical practice around the gut-brain connection have helped to develop a model in which the psychologist can be an important part of a multidisciplinary team treating patients with chronic pelvic pain.

In The Role of Psychologists in Treating Pelvic Pain, which was published recently in Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery, Dr. Gernand and co-authors highlight the need for an integrated treatment approach. This might include multiple evidence-based treatments, including cognitive behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, sex therapy and hypnosis, as well as collaboration with medical and psychological caregivers in the development of a treatment plan.

Advertisement

CPP is pain associated with symptoms that occur from the belly button to the mid-thigh. It may include any organs in the pelvic compartment.

“With pelvic pain, there's obviously the biological piece, whether the pain is from the organs or muscles or from the nervous system itself,” says Dr. Gernand. “It doesn’t always show up as any kind of damage on a test, but if we were to put that person in a scanner, we would see that somatosensory cortex lighting up.”

Pelvic floor muscle dysfunction can cause significant pain and lead to bowel and bladder problems, so often patients present with additional conditions, such as vulvodynia, irritable bowel syndrome and other gut issues. Typically, patients are referred for pelvic-pain psychological care if they are experiencing considerable distress related to their symptoms.

The complexity of treating CPP is attributed in part to individual differences in pain perception as well the body-to-brain-to-body feedback loops. Additional psychological factors can include pre-existing stress, anxiety, depression, previous medical or sexual trauma, and threatening beliefs about the pain. Dr. Gernand clarifies that anxiety and depression often develop in response to the challenges of living with chronic pain and do not “cause” it — and that chronic pain involves a complex interplay between biological factors and a person’s entire lived experience.

“We used to think of pain processing this way,” she says. “First, there's some kind of damage or injury. The nerves take that signal up to the spine, the spine sends it to the brain, and then we feel the pain. But now we know about the downward direction of pain processing. So yes, that signal arrives, but there are actually over 40 parts of the brain involved in pain processing. One part helps us register the sensation of pain, but another part processes the sense of unpleasantness or suffering. A whole other part assesses whether there is damage to the body or whether the body is in danger. The hippocampus contains memories related to the pain, and the prefrontal cortex plays a very powerful role in assigning meaning to the pain.

Advertisement

“That information gets fed back down into the brainstem, which can alter activity in the spinal cord, increasing or decreasing the amount of pain signals that get through to the brain,” she says.

Dr. Gernand uses the metaphor of someone walking through the forest who has been told there will be snakes all around ready to jump up and bite. “At some point, if you step on a stick and it pokes you in the leg, you’re going to feel a snakebite. This is not a mushy ‘feelings’ thing. This is how our body and mind work together to help us survive.”

A fundamental aim of treatment is to create safety for the patient. Dr. Gernand begins by reviewing the patient’s records and then helping them tell their story. Pain affects individuals differently, so the patient’s perspective is crucial.

For some people, she says, the hardest part may be just dealing with the severity of pain they feel. Others may struggle because they have trouble sitting at work or because pain is interfering with relationships.

In addition to getting a sense of what is contributing to this individual's distress, she considers other medical, mental health and social factors. Toward the end of the appointment, she helps the patient identify goals. These might be finding techniques for “turning down the dial” on the pain itself or establishing ways to reduce the negative impact of the pain on their lives.

“Sometimes it is very straightforward. We do some hypnosis, they get some tools, and that’s all they needed,” she says. “Other times it requires a bit of soul searching. Somepeople have been in survival mode for so long that the things that are important to them, like time outside or time with friends or family, get pushed to the periphery and they don't feel like themselves anymore.”

Advertisement

Helping patients become reacquainted with what is important to them is an essential part of treatment, although it’s not always easy. Those who want to reconnect socially may venture into situations in which they may be less in control over their symptoms or that necessitate “making the invisible visible” — for example, standing when others are sitting, or discussing anticipated intimacy challenges with a potential romantic partner. But those hurdles can yield therapeutic wins.

“When that's done in service of something very important to you, it can change the meaning of the pain and the difficult emotions that come with it,” says Dr. Gernand. “So it’s no longer something that is preventing me from living my life, but rather something that I'm willing to encounter while I live my life.”

Individual psychotherapy for pelvic pain typically takes place over eight to 12 sessions, with a close focus on the pain and its effects. It’s common, however, for patients to present with existing mental health conditions, including depression or anxiety, which often intersect with their pain experience.

A group therapy program also is being established, says Dr. Gernand. The eventual aim is for that to become the primary treatment modality.

“There's a special essence in group therapy that women can't really get out of individual therapy, which is coming to know others who are going through something very similar,” she says. “Some women with pelvic pain have negative beliefs about themselves because of the connection with sexual functioning and fertility. When they develop fondness for other group members, they find that in no way are they thinking of them as ‘broken.’ And that can make them question their negative beliefs have about themselves.”

Advertisement

There are a few considerations for primary care or women’s health providers who have pelvic-pain patients they think might benefit from psychological interventions.

First, it’s important to know if a patient has a history of sexual trauma. That can affect how medical and psychological care is delivered, and in some cases the patient may need trauma-focused therapy before other treatment can begin.

Second, understanding the pain/mental health dynamic is necessary for delivering optimal care. “Sometimes physicians can come to believe that anxiety and depression can cause pain, and they pin the pain on anxiety or depression. That is not how it works,” says Dr. Gernand. “Pain is pain regardless of whether there are underlying mental health problems. We need to keep this complex, bi-directional picture in mind.”

Advertisement

Benefits include reduced pain, earlier mobilization and more likely discharge to home

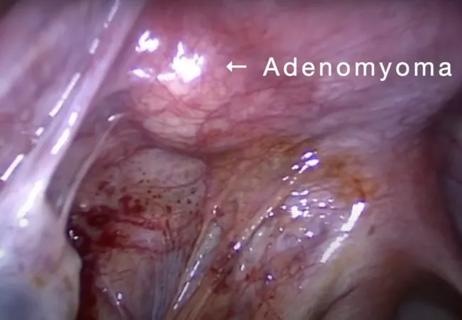

Laparoscopic surgery provides relief for teenage patient with adenomyoma and endometriosis

Prolapse surgery need not automatically mean hysterectomy

Specialist teams can improve outcomes and reduce risks

Personalized reconstruction is an alternative to leg amputation or flail limb

New guidelines let the patients steer the process

Novel program is life changing for patients and families

Study indicates patients can have confidence about potential outcomes