Volume and versatility enable success in a case once deemed too complex

By Michael Tong, MD, MBA, and Shinya Unai, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A gentleman in his mid-60s with a history of smoking presented to an outside institution with worsening shortness of breath, orthopnea and lower extremity edema. CT showed severe emphysematous changes and basilar scarring compatible with advanced idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease component. V/Q scan revealed mismatched ventilation-perfusion defects suggesting chronic pulmonary embolism that led to severe pulmonary hypertension. Echocardiogram showed normal left ventricular function, but the right ventricle was severely dilated and the function was moderately poor; he also had severe tricuspid regurgitation.

Over the next three months, the patient became increasingly symptomatic, requiring up to 8 liters of oxygen with activity. He was referred for lung transplantation at his local transplant program but was turned down when it was discovered that he also had severe triple-vessel coronary artery disease (CAD). Given his age, pulmonary hypertension, tricuspid regurgitation and severe CAD, his case was considered too complex and too high-risk.

He was referred to Cleveland Clinic for a second opinion. Undeterred by his advanced disease complexity, he remained motivated and worked hard to maintain his level of fitness despite the need for escalating doses of oxygen. Our committee accepted him for combined double lung transplantation, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) and tricuspid valve repair, and he was placed on the transplant waitlist.

Advertisement

About four weeks after the patient’s listing, a suitable lung donor was identified and the patient was brought to the OR. Following median sternotomy, left internal thoracic artery (LITA) was harvested in a skeletonized fashion. Saphenous vein was harvested endoscopically. He was heparinized and placed on cardiopulmonary bypass. Antegrade and retrograde cardioplegia was induced to achieve cardiac arrest.

The vein grafts were anastomosed to the obtuse marginal and posterior descending arteries, and the proximal ends were then anastomosed to the ascending aorta. The cross-clamp was removed and the heart began to beat again. The hilar structures of both lungs were dissected free, and when the organs arrived in the OR, the left lung was removed and the donor left lung was implanted; the same was done on the right side. Finally, grafting of the LITA to the left anterior descending artery (LAD) was performed, and the tricuspid valve was repaired with a 30-mm tricuspid rigid annuloplasty ring.

The patient fared well postoperatively. Initial fluid overload was treated with diuretics. He was extubated on postoperative day 5 and transferred to the step-down unit on day 8. His postsurgical recovery was rapid, presumably thanks to his level of fitness, and he was discharged home on postoperative day 15. He continues to do well one year postoperatively.

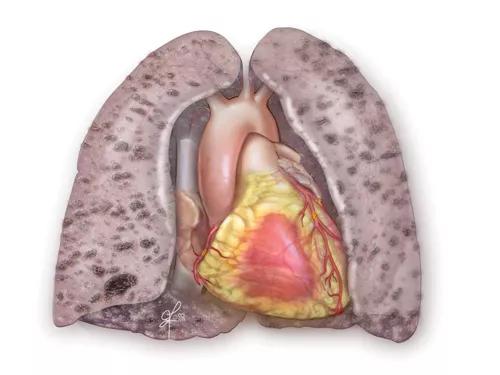

The combination of CAD and end-stage lung disease (Figure 1) is common as well as a predictor of complexity and risk.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/757f9ce3-97e0-464e-a2f7-f0c0f847532a/Tong-Fig-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Illustration of fibrotic lungs with concomitant coronary artery disease.

Advertisement

Typically a patient with CAD waiting for lung transplantation would be offered percutaneous coronary intervention prior to transplant, but three to six months of dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) would then be required and the patient could be listed only after stopping the clopidogrel, due to a prohibitive risk of bleeding during surgery. Given our patient’s rapid rate of decline, he probably would not have had six months to live under such a scenario. Similarly, patients with end-stage lung disease may have other cardiac abnormalities such as aortic stenosis and tricuspid regurgitation. Our patient had developed secondary pulmonary hypertension that in turn caused increased right ventricular strain and tricuspid valve regurgitation.

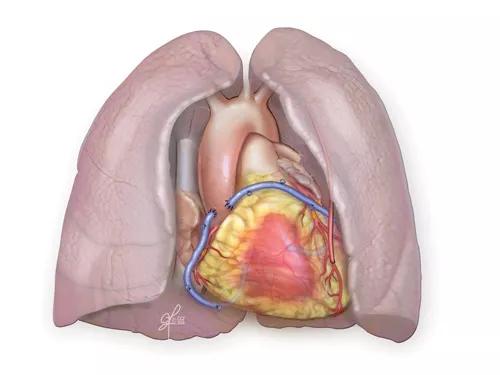

Various operative sequences are possible when it comes to performing combined CABG and lung transplantation. To shorten the operation’s duration, we typically would perform the CABG first while waiting for the donor lungs to arrive (Figure 2, with the completed combination procedure shown in Figure 3). This also provides increased coronary blood flow, which can be protective against intraoperative myocardial infarction.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/cb7f21fe-db1e-4351-8891-9c8d11aea069/Tong-Fig-2_jpg)

Figure 2. CABG performed prior to lung transplantation.

However, if the LITA-to-LAD bypass is performed with an in situ LITA graft, it can make the left lung explant and implant more difficult. Therefore, the LITA-to-LAD bypass can be done after the left lung is implanted or the LITA can be used as a free graft. Likewise, if the patient needs a mitral valve replacement, this should be done after the left lung transplant to avoid the risk of atrioventricular groove disruption when lifting the heart to access the left chest.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/6143b0fe-098b-445c-a984-9e8cf7cbb7e1/Tong-Fig-3_jpg)

Figure 3. Completed combined CABG/double lung transplant.

At most centers, the presence of concomitant cardiac disease during lung transplantation requires two separate surgical teams: a thoracic surgeon for the lung and a cardiac surgeon for the heart. Given the unpredictable nature and timing of transplantation, this can pose a logistical challenge, which prompts many centers to turn down such patients. Currently, 15 to 20 percent of Cleveland Clinic lung transplant recipients have been turned down by other programs, in many cases due to the presence of CAD.

At Cleveland Clinic, we have a team of three cardiac surgeons and one thoracic surgeon performing lung transplantation, which gives us the versatility to offer combined surgeries to patients without additional surgical risk and without logistical challenges. This versatility, together with cardiac surgery and lung transplant volumes that are among the very highest in the nation, makes our team uniquely well prepared to offer surgery to complex patients like this who have no other options.

Dr. Tong is a staff surgeon and Dr. Unai is a cardiothoracic surgery fellow, both in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery.

Advertisement

Advertisement

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Multimodal evaluations reveal more anatomic details to inform treatment

Insights on ex vivo lung perfusion, dual-organ transplant, cardiac comorbidities and more