Questions remain following late mortality signal from a retrospective cohort study

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f4270a8e-403d-4c31-a7d6-7417c1a23779/22-HVI-2935765-CQD-vs2-650x450-1_jpg)

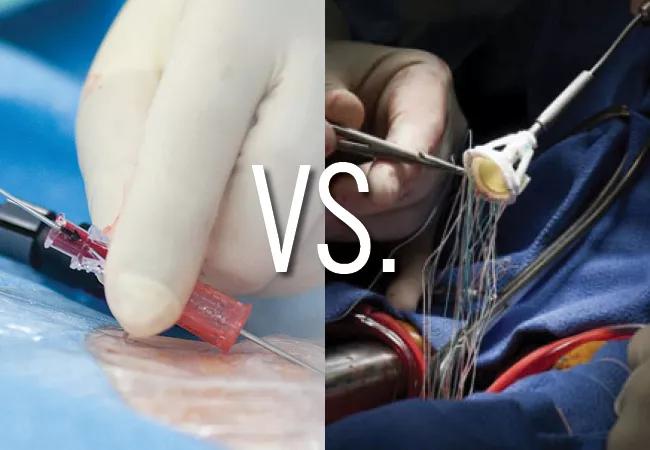

side-by-side procedural images of TAVR and SAVR

Relatively young patients who undergo surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) with a bioprosthetic valve are likely to need reintervention later in life due to structural bioprosthesis degeneration. Choosing the best valve replacement strategy in these patients — either redo SAVR, the traditional standard of care, or the fast-expanding option of valve-in-valve (ViV) transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) — has been a clinical challenge.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Now a new retrospective cohort study comparing these two options for SAVR valve failure has found that ViV TAVR offered initial advantages but also a higher risk of mortality and heart failure hospitalization starting two years after the procedure. The study was recently published in JAMA Cardiology by a multicenter research group that included A. Marc Gillinov, MD, Chair of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery at Cleveland Clinic.

“The reasons underlying the late excess mortality and heart failure hospitalizations with valve-in-valve TAVR versus redo SAVR are not clear,” Dr. Gillinov says. “This issue deserves further study, as our results may be affected by residual confounding even after the propensity matching that we did. In the meantime, these findings may argue for some caution regarding the rapid adoption of valve-in-valve TAVR, especially in younger patients and those at lower surgical risk.”

The study used administrative databases from three states — California, New York and New Jersey — to assess long-term outcomes among patients undergoing ViV TAVR or redo SAVR for a failed bioprosthetic SAVR valve from 2015 to 2020. Patients were excluded if their ViV TAVR or redo SAVR procedure was performed within five years of their initial SAVR or if they underwent a concurrent surgical procedure or had infective endocarditis.

Among 6,118 patients in the databases who had an aortic valve replacement after SAVR valve failure, 1,771 patients met the criteria for inclusion in the analysis. They had a mean age of 74.4 years and were followed for a median of 2.3 years. Of these patients, 1,348 (76%) underwent ViV TAVR and 423 (24%) underwent redo SAVR.

Advertisement

In the overall cohort, patients in the ViV TAVR group differed significantly from those in the SAVR redo group in that they:

To adjust for selection bias based on these or other characteristics, propensity score matching was used, identifying 375 patient pairs well matched by age, demographics, comorbidities and additional factors. All-cause mortality within the propensity-matched cohort was the primary outcome measure.

Analysis of the overall cohort showed that the share of patients undergoing ViV TAVR increased steadily and markedly throughout the study period, from 35.3% of patients in 2015 to 62.5% in 2019 (P < .001).

Within the propensity-matched cohort, periprocedural mortality and stroke rates were comparable between the matched groups. However, the ViV TAVR group had significantly lower periprocedural rates of major bleeding (2.4% vs. 5.1%; P = .05), acute renal failure (1.3% vs. 7.2%; P < .001) and new pacemaker implants (3.5% vs. 10.9%; P < .001), as well as shorter recovery times.

In the propensity-matched cohort, mortality was statistically comparable between the groups up to two years but diverged thereafter, with a higher rate in the ViV TAVR group (hazard ratio [HR] = 2.97; 95% CI, 1.18-7.47). By five years, all-cause mortality was 23.4% with ViV TAVR compared to 13.3% with redo SAVR. A similar pattern was seen with heart failure hospitalizations, which were similar between the groups up to two years but higher with ViV TAVR thereafter (HR = 3.81; 95% CI, 1.57-9.22).

Advertisement

The propensity analysis showed no significant differences between groups in five-year rates of stroke, reoperation, major bleeding or infective endocarditis.

“This study is notable both for documenting a significant proportional increase in the use of valve-in-valve TAVR over this five-year period and for indicating a higher risk of late mortality and heart failure hospitalization with valve-in-valve TAVR versus redo SAVR,” Dr. Gillinov observes.

At the same time, he and his co-authors note the limitations of the study, including its reliance on retrospective data from administrative databases without information on factors such as the type and size of the initial and replacement bioprosthetic valves. They write: “To what extent the observed differences stem from patient imbalances, bias, or procedural limitations warrants further exploration and in younger patients highlights the critical need for a randomized comparative effectiveness trial of ViV TAVR vs. redo SAVR.”

Cleveland Clinic Cardiovascular Medicine Chair Samir Kapadia, MD, who was not involved in the study, agrees about the limitations of the analysis and adds that it addresses a question that is often influenced by patients’ desire to avoid another surgery. “Most patients with a bioprosthetic SAVR valve that is failing are not interested in considering another surgery just for their aortic valve because they’ve already had aortic valve surgery,” he says, pointing out that more than three-quarters of patients in this analysis opted for ViV TAVR after exclusion of those who needed concomitant procedures or who had endocarditis.

Advertisement

Dr. Kapadia notes that life expectancy is crucial in all decisions involving aortic valve replacement, including the choice between redo SAVR and ViV TAVR for a failed SAVR valve. To optimize patients’ outcomes and quality of life, he advocates a heart team-based lifetime management approach.

“Lifetime management should be considered in deciding between the SAVR and TAVR options,” he says. “It is best to have the last valve procedure during a patient’s lifetime be TAVR and, if possible, to not have more than one valve-in-valve procedure (that is, avoid having more than two valves at any given time) and to operate on patients when they are younger and healthier.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Experience-based takes on valve-sparing root replacement from two expert surgeons

30-year study of Cleveland Clinic experience shows clear improvement from year 2000 onward

Surgeons credit good outcomes to experience with complex cases and team approach

For many patients, repair is feasible, durable and preferred over replacement

In experienced hands, up to 95% of patients can be free of reoperation at 15 years

Experience and strength in both SAVR and TAVR make for the best patient options and outcomes

Ideal protocols feature frequent monitoring, high-quality imaging and a team approach