Case study underscores need for rapid recognition, repair

By Siva Raja, MD, PhD; Dean Schraufnagel, MD, Eric Roselli, MD; and Oussama Wazni, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 54-year-old man underwent repeat ablation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation at an outside hospital. He was otherwise in good health. About 10 days after the repeat procedure, he was admitted to the same hospital with vague complaints of chest pain. He was diagnosed with pericarditis and discharged home the next day.

Five days later, he was readmitted with chest pain, abdominal bloating, fever and chills, right hemiparesis, aphasia and new onset of seizures. Workup with CT and echocardiography showed pneumocephalus, pneumomediastinum and pneumopericardium.

The team, including a gastroenterologist and a cardiac surgeon, diagnosed an atrio-esophageal fistula and attempted to repair it. They first performed an endoscopy, which revealed a mid-esophagus perforation 10 mm long by 4 mm wide with pulsation detected at the base of the tear. The surgeon covered the perforation with a 10-mm-by-100-mm esophageal stent.

They next conducted a median sternotomy and started full cardiopulmonary bypass. The pericardium was opened, and purulent fluid was found and drained. A 1.5-cm hole in the floor of the left atrium with exposed esophageal tissue was located; it was excluded from the inside with a bovine pericardial patch. The patient was rewarmed and closed.

Two days later, the patient was extubated and appeared to be recovering. However, his neurological symptoms recurred when he restarted oral intake, at which point he was transferred to Cleveland Clinic for further management.

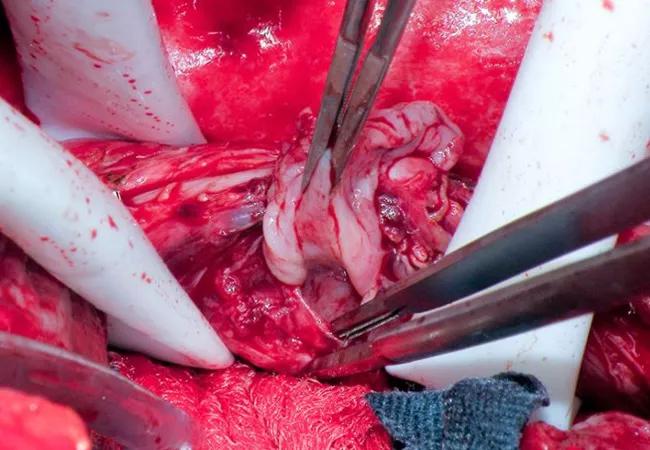

On arrival to our institution, the patient was immediately evaluated with IV contrast CT (Figure 1), which showed the esophageal stent abutting the left atrium and a rim of air outside the stent.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/22443177-e419-4251-9ea4-5e95003e7c27/18-HRT-118-Big-Rescues-CQD-Inset-1_jpg)

Figure 1. Contrast CT upon presentation at Cleveland Clinic showing the esophageal stent abutting the left atrium, with a rim of air visible outside the stent (arrow).

A right thoracotomy was performed, based on the reasoning that it would provide better access to the esophageal fistula (although more challenging access to the left atrium). An intercostal muscle flap was taken in order to buttress the repair of the fistula and to create separation between the repair of the esophagus and the atrium. Empyema was incidentally found, requiring lung decortication.

The area of the fistula was identified, and the esophagus was controlled above and below. After separating the esophagus from the atrium, an endoscopy was performed to remove the stent to allow better visualization of the esophagus and the left atrial defect. Active bleeding from around the side of the atrial patch was seen, and the decision was made to go on cardiopulmonary bypass.

The right common femoral artery and right atrium were cannulated, and cardiopulmonary bypass was started. Sufficient blood volume was maintained in the left atrium to avoid air embolization. The left atrial defect was more widely exposed, and large sutures were placed through the atrial wall surrounding it. The internal patch was left in place and a new piece of bovine pericardium was parachuted down over the defect from the outside and tied into position.

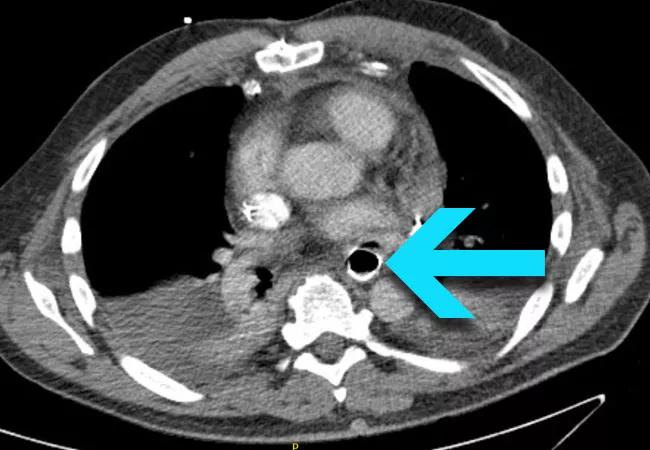

Next, a two-layer repair was performed in the esophagus by closing the submucosa as well as the muscle, soft tissue and adventitia above it. Endoscopy was performed to confirm the seal. The intercostal muscle flap was sutured onto the esophagus between the esophageal and left atrial defects. The three panels of Figure 2 (below) show various stages of the repair.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/ee948473-7168-4683-bcb4-832502325496/18-HRT-118-Big-Rescues-CQD-Inset-2_jpg)

Figure 2. Top image shows the full-thickness esophageal defect. Middle image shows primary repair of the esophageal defect. Bottom image shows the intercostal muscle flap.

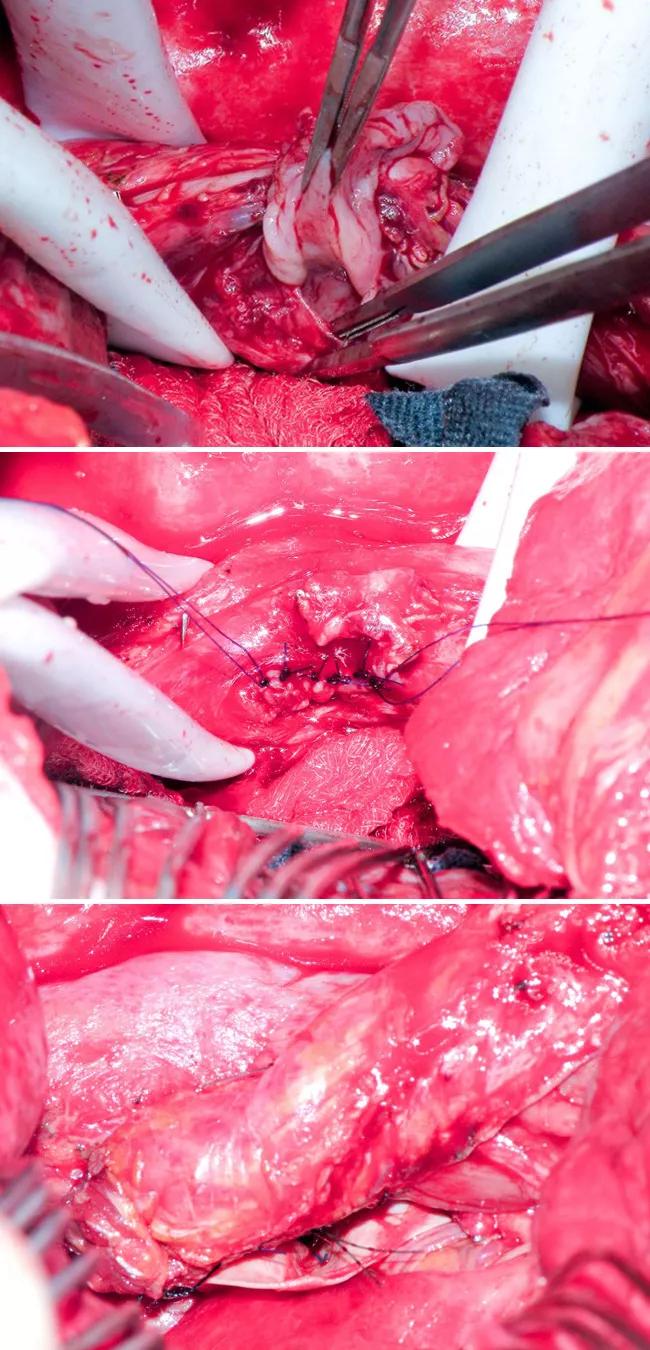

Three months later, endoscopy showed excellent healing (Figure 3) and the patient was back to work and eating a regular diet. He felt completely recovered except for mild residual weakness in one hand.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/93f3aeec-54ba-4dd3-9298-a6cf9ed6d28b/18-HRT-118-Big-Rescues-CQD-Inset-3_jpg)

Figure 3. Endoscopy image taken three months postoperatively showing excellent healing with one suture visible.

Prompt fistula recognition is critical. Fistula formation is a very rare but recognized complication of atrial ablation, occurring in about 1 in 2,000 cases. As was the case for this patient, sepsis and neurological symptoms usually manifest in about two weeks, although they can arise as late as six weeks after ablation. Rapid recognition and repair are critical: Without correction, mortality is 100 percent, usually within 24 hours of symptom onset.

Within a week or two after atrial ablation, patients commonly present with chest pain, especially associated with breathing and sometimes swallowing. Usually an echocardiogram is done, pericarditis is diagnosed and pain relief is provided. A fistula is not usually considered (and an echo would not help detect it) unless the pain persists or other signs develop.

Endoscopy with atrio-esophageal fistula is contraindicated. The fact that the patient did not present with hematemesis indicated that blood from the atrium was not entering the esophagus but rather that contents from the esophagus were entering the atrium. The direction of flow makes the danger of causing an air embolus during insufflation extremely high. If absolutely necessary, endoscopy can be performed using hyperbaric oxygen or CO2.

Advertisement

Surgical drainage and repair are essential. Esophageal stenting will not result in a healed fistula.

Avoiding this complication is not easy.No technique to keep the esophagus out of harm’s way during atrial ablation is surefire. If the esophagus is right next to the posterior wall of the atrium, it may be best to avoid ablating there. But the esophagus is mobile and stretchy, so even doing a CT scan or barium swallow ahead of the ablation may not reveal its location during the procedure.

Monitoring the temperature in the esophagus using a thermistor throughout the ablation may help. This is routinely performed at Cleveland Clinic. The tip of the transesophageal probe can be guided with the help of fluoroscopy to the area where the ablation is occurring. But again, not knowing the exact position of the esophagus significantly limits the effectiveness of this technique. Cooling the esophagus with cold water during ablation is also under investigation, but this complication is so rare that proving benefit for any of these methods may ultimately be impractical.

Ablation is usually safe.According to the literature, the risk of death from ablation for atrial fibrillation is about 1 in 1,000, and is mostly due to tamponade. Institutions with small volumes can have much higher rates, whereas Cleveland Clinic, with our large caseload, has 1 death in about 11,000 ablations.

Dr. Raja is a thoracic surgeon and Surgical Director of the Center for Esophageal Diseases, Dr. Schraufnagel is a cardiothoracic surgery resident, and Dr. Roselli is Chief of Adult Cardiac Surgery, all in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. Dr. Wazni is Section Head of Cardiac Electrophysiology and Pacing in the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients