Lessons in the combined presentation of two formidable conditions

Surgical treatment of hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy (HOCM) and Barlow’s valve involves notably complex procedures that most cardiothoracic surgeons rarely perform. So when mitral valve prolapse occurs in addition to HOCM, requiring both problems to be repaired, surgical complexity is increased substantially.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“The combination of HOCM and Barlow’s is very challenging, since the standard treatment for one is counterproductive to the other,” says Cleveland Clinic cardiothoracic surgeon Per Wierup, MD, PhD.

Cleveland Clinic has become a national and international referral center for patients needing surgery for these conditions. Additionally, a minimally invasive robotic procedure for repairing Barlow’s valve is producing ideal results and is now standard procedure at Cleveland Clinic.

Surgical skill and experience allowed for a successful outcome in the following case of a patient needing a septal myectomy for HOCM along with mitral valve repair for Barlow’s.

In July 2019, a 38-year-old man was admitted to an area hospital after fainting. He had been diagnosed with HOCM seven months before and was started on beta-blocker therapy. As his symptoms worsened, the dosage was gradually raised, and he received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Despite these measures, he suffered multiple episodes of dizziness and syncope. With the latest episode, he requested a transfer to Cleveland Clinic.

He was seen in the emergency department by cardiologist Russell Raymond, DO. The patient was alert and awake, severely dyspneic and suffering from chest discomfort.

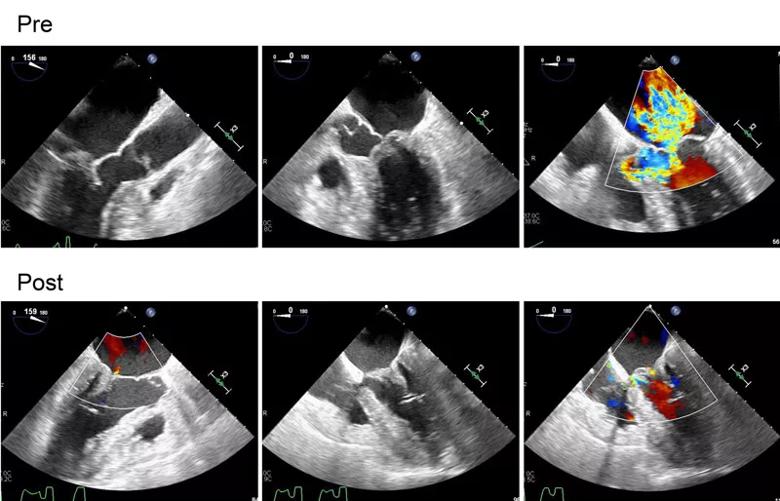

Upon auscultation, Dr. Raymond noted a loud murmur, indicating severe mitral valve insufficiency. Echocardiography confirmed severe HOCM with systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve (Figure) and an outflow tract gradient exceeding 100 mm Hg. In addition, there was significant mitral valve prolapse consistent with Barlow’s valve. Urgent surgery was recommended.

Advertisement

A team led by Dr. Wierup performed a septal myectomy and repaired the patient’s mitral valve using a novel technique that repositions the leaflets for virtually perfect coaptation without cutting or suturing (the technique is profiled in this recent Consult QD post). The repairs were checked with intraoperative echocardiography and found to be successful (Figure).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/da9dacf6-468f-4279-b292-6729a055b590/19-HRT-3883-Wierup-CQD-Inset_jpg)

Figure. Pre- and postoperative echocardiograms from the case patient. (Top row) The preoperative images depict septal hypertrophy with severe obstructive systolic anterior motion (SAM) and the Barlow type of mitral valve with excessive tissue and prolapse of the tall posterior leaflet. Note that the severe mitral regurgitation jet is centrally directed due to a combination of posterior prolapse (expected anteriorly directed jet) and the SAM-related regurgitation (which normally results in a posteriorly directed jet). (Bottom row) The postoperative images show results after the wide and apically directed myectomy together with papillary muscle reorientation and Gore-Tex chordal reconstruction of the prolapsing mitral valve. Note laminar flow in the left ventricular outcome tract and trivial mitral regurgitation.

Before the heart-lung machine was disconnected, isoproterenol was given to lower the patient’s blood pressure and provoke tachycardia. “This protocol provides an additional guarantee that the heart is working as it should, even in the most extreme situation,” Dr. Wierup explains. “We want the repair to endure for the rest of the patient’s life.”

Advertisement

The patient was discharged six days after surgery. After postoperative checkups with Drs. Wierup and Raymond, he has returned to his local cardiologist for echocardiographic follow-up every six to 12 months. Although the surgical repair is expected to be long-term, lifelong follow-up will be required.

Combined presentation of HOCM and Barlow’s valve is uncommon, and some physicians may be unfamiliar with best practices for treating these conditions. Drs. Wierup and Raymond offer the following general guidance when managing them concurrently:

“HOCM is a complex disease that requires nuanced care by experienced cardiologists and cardiac surgeons,” comments Milind Desai, MD, a Cleveland Clinic cardiologist with a specialty interest in HOCM. “While medical therapy remains the initial line of treatment, a significant proportion of patients require surgical relief of LVOT obstruction. It is crucial to understand the mitral valve’s role in causing LVOT obstruction. In many patients, surgical myectomy alone may not be sufficient and may need to be combined with mitral valve repair techniques. A well-performed operation can provide long-lasting relief of symptoms and improved quality of life.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Initial data indicate tolerability and promising cardiac remodeling effects

LLM-driven system uses both structured and unstructured data, provides auditable justifications

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most