An overview from our experts

By Manuel Ribeiro Neto, MD, Emer Joyce, MD, PhD, Christine Jellis, MD, PhD, Rory Hachamovitch, MD, and Daniel Culver, DO

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

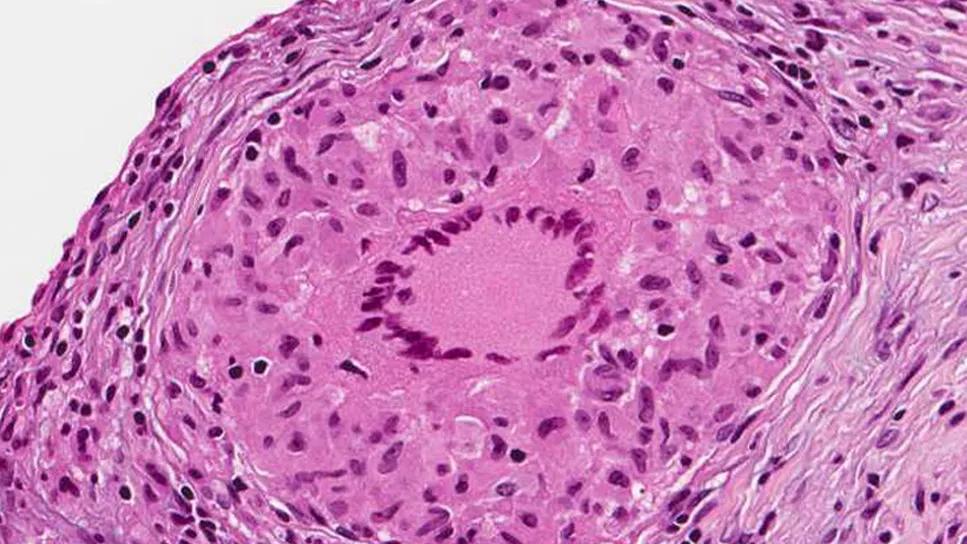

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown etiology, characterized by non-necrotizing granulomas. Symptomatic cardiac involvement occurs in only 2 to 5 percent of patients, but screening with MRI or autopsy studies reveals a prevalence closer to 25 percent. The relevance of those subclinical cases is unknown, but many are unlikely to develop clinically significant disease.

The most common manifestations of cardiac sarcoidosis are atrioventricular block, ventricular arrhythmia and heart failure. Less common are bundle branch blocks, atrial arrhythmias, valvular abnormalities, pericardial effusion and sudden cardiac death. Although non-specific chest pain is extremely common in sarcoidosis, it is not usually a manifestation of cardiac sarcoidosis.

Patients with sarcoidosis should be screened with history (significant palpitations, presyncope or syncope, unexplained dyspnea) and electrocardiogram. Echocardiogram and Holter monitor testing are useful when initial screening is suggestive. If any abnormality is encountered, advanced cardiac imaging should be performed.

There is no reference standard in cardiac sarcoidosis. The sensitivity of endomyocardial biopsy is low (30 percent). Three sets of clinical criteria have been proposed: the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare (JMHW), the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) criteria.

Cardiac PET has been compared to the JMHW criteria in at least seven studies (sensitivity 79-96%, specificity 68-86%). Based on perfusion and inflammation [the latter with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)] imaging, there are four possible results: normal (normal perfusion with no inflammation), early stage (normal perfusion with inflammation), advanced stage (abnormal perfusion with inflammation) and end stage (abnormal perfusion with no inflammation). Cardiac MRI also performed well (sensitivity 76-100%, specificity 78-92%) in two studies utilizing the JMHW criteria and endomyocardial biopsy, respectively, as the gold standard. Findings include regional wall motion abnormalities with or without wall thinning in a noncoronary artery distribution, increased signal on T2-weighted imaging suggestive of inflammation, and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE). The pattern of LGE is typically patchy, mid-myocardial or epicardial and in a non-coronary distribution. LGE can be seen in both active disease (due to inflammation) and in scar.

Advertisement

The results of cardiac PET and MRI need to be interpreted with caution. Although there are typical imaging findings observed as described above, cardiac sarcoidosis can always masquerade with patterns suggestive of other disease etiologies. As such, there is still uncertainty around important aspects of these tests and no consensus on which test is preferable. A multidisciplinary approach involving pulmonologists, cardiologists and advanced cardiac imaging specialists is recommended and available at reference centers to integrate clinical and imaging findings.

Differential diagnosis should include:

A multidisciplinary approach to therapy is critical. Depending on the clinical manifestations, specialists in sarcoidosis, advanced cardiac imaging, heart failure and cardiac electrophysiology should be involved. Those specialists are readily available at our institution, allowing us to offer integrated care to our patients.

Medical therapy

Corticosteroids (CS) are the first-line agent to treat active inflammation. The dosing needs to be individualized, and it varied in a meta-analysis from 20 mg of prednisone daily to pulse therapy in more severe cases. Depending on the severity of the disease and the complications caused by CS, it is reasonable not to use CS at all in some selected cases.

Advertisement

Second-line agents are methotrexate, leflunomide, azathioprine, mycophenolate and hydroxychloroquine. There are no head-to-head comparisons between those agents, so which agent to use depends on expert opinion. In our Sarcoidosis Center, we favor methotrexate and leflunomide. We also favor starting a second agent early in the process, ideally at the same time CS are started. This approach decreases the patient’s exposure to CS and its undesirable side effects.

Third-line agents are the tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) antagonists infliximab and adalimumab. A randomized controlled trial of infliximab in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis showed a reduction in extra-pulmonary organ involvement severity. Based on this study and others, TNFα antagonists are recommended as third-line therapy by sarcoidosis experts.

Non-immunosuppressive medications targeting specific cardiac manifestations of sarcoidosis should also be used. They include heart failure medications and antiarrhythmic medications.

Device/ablation therapy

The use of the electrophysiology armamentarium should follow HRS guidelines. A permanent pacemaker should be placed in high-degree atrioventricular block even if it reverses transiently. An implantable cardiac defibrillator (ICD) should be placed in patients with spontaneous sustained ventricular arrhythmias, prior cardiac arrest, ejection fraction (EF) ≤ 35 percent despite optimal medical therapy, and in patients who are having a pacemaker. In patients with EF between 36 and 49 percent despite optimal medical therapy, ICD implantation may be considered (an electrophysiology study could help stratify the sudden death risk). Ablation therapy is an option in patients with refractory ventricular arrhythmias.

Advertisement

The prognosis of patients with clinically overt cardiac sarcoidosis was demonstrated in a recent study from Finland. One-, 5- and 10-year transplant-free cardiac survival rates were 99.1, 93.5 and 89.3 percent, respectively. Heart failure/low EF predicted worse survival. Other predictors are age ≥ 46 years, extent of mismatch defect in cardiac PET, and extent of LGE in cardiac MRI. The prognosis of patients with subclinical cardiac sarcoidosis is controversial.

As a World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) Sarcoidosis Clinic, we provide a multidisciplinary approach to patients with cardiac sarcoidosis and continue to research treatment approaches.

Dr. Ribeiro is staff in the Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine. Dr. Jellis is associate staff in the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine and in Diagnostic Radiology. Dr. Culver is Director of the Sarcoidosis and Interstitial Lung Disease Program and has a joint appointment in the Department of Pathobiology.

Advertisement

Advertisement

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Multimodal evaluations reveal more anatomic details to inform treatment

Insights on ex vivo lung perfusion, dual-organ transplant, cardiac comorbidities and more