How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/de6f5513-5866-4a99-9319-8e0db1b375ab/25-HVI-6845762CQD-TMVR-feature)

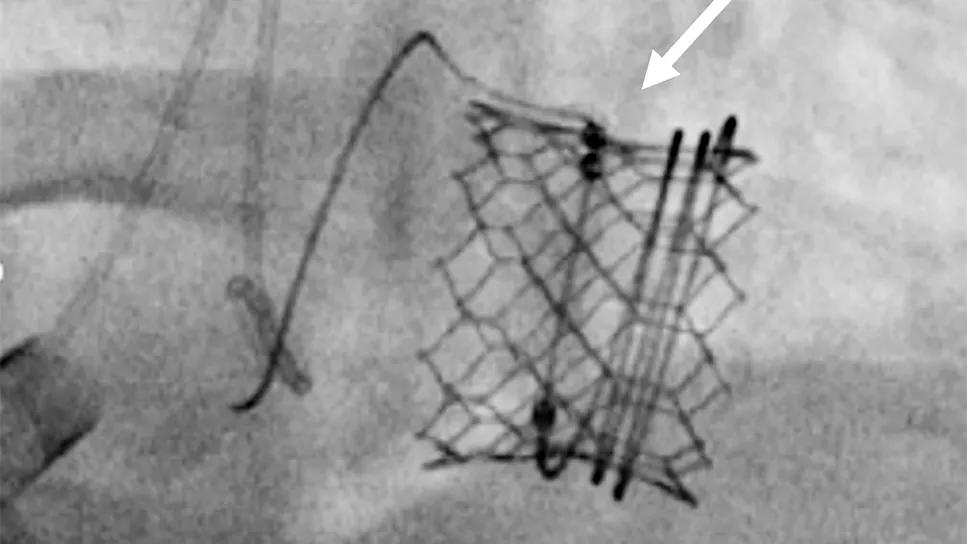

scan of an implanted stented heart valve

For most patients with symptomatic severe or moderate-to-severe mitral regurgitation (MR), surgical mitral valve repair is the gold standard for delivering excellent and durable outcomes. For those at prohibitive surgical risk, transcatheter edge-to-edge repair of the mitral valve (M-TEER) is a safe and efficacious alternative, with growing evidence for consideration of M-TEER in selected patients at lower risk.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Despite these strong treatment options, some patients who are not surgical candidates have complex mitral valve anatomies for which M-TEER may not deliver durable freedom from MR. Such patients stand to benefit from a reliable transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR) option, which — unlike M-TEER — could also allow for future reintervention with percutaneous valve-in-valve implantation in the event of structural valve deterioration.

“There is no clear indication yet on when to use TMVR for patients with native mitral valve degeneration,” says interventional cardiologist Samir Kapadia, MD, Chair of Cardiovascular Medicine at Cleveland Clinic. “Currently, we are using it on patients who are not M-TEER or surgical candidates.”

Nevertheless, the quest for a reliable TMVR option for native valve replacement is showing signs of progress, with Dr. Kapadia and Cleveland Clinic colleagues actively involved in various trials of TMVR systems. Meanwhile, they are expanding on their pioneering work in using TMVR to rescue failing bioprosthetic mitral valves and annuloplasty rings and to treat patients with mitral annular calcification.

“For these high-risk individuals, TMVR is an attractive alternative,” says Amar Krishnaswamy, MD, Section Head of Invasive and Interventional Cardiology.

The primary challenge inherent in TMVR is having a large enough opening to accommodate sufficient blood flow following insertion of a transcatheter valve inside the native valve.

Device manufacturers have approached this problem in various ways, developing multiple TMVR systems with transcatheter mitral valves of different characteristics and sizes. Cleveland Clinic has participated in clinical trials of five such systems.

Advertisement

Encouraging one-year outcomes were recently reported from one of those studies — the ENCIRCLE multicenter trial of the SAPIEN M3 system (Lancet. 2025;406:2541-2550), which showed sustained MR reduction and procedural safety comparable to M-TEER.

“Thirty-day mortality was 0.7%, while the estimated surgical mortality rate was 6.6%,” notes Dr. Krishnaswamy. “These are encouraging outcomes in patients who were at very high risk for cardiac surgery and may not have had any other option.”

Based in part on the ENCIRCLE findings, the M3 system (Figure 1) was approved by the FDA in December 2025. It is the first transseptal TMVR device approved in the U.S., joining the previously approved Tendyne system, which is delivered transapically.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/336e638f-6d40-4c4a-a24e-c50c6b2dd549/25-HVI-6845762CQD-TMVR-inset1)

Figure 1. Placement of the M3 balloon-expandable valve for TMVR. A “dock” is placed in the mitral subvalve (left), after which the balloon-expandable valve is placed inside the dock (middle). An echocardiogram shows the valve in place (right).

At this time, Cleveland Clinic reserves TMVR devices for patients who are not anatomically suitable candidates for M-TEER. That represents about 30% of patients who need treatment for MR but are not surgical candidates.

However, due to clinical trials’ anatomic exclusion criteria, 60% to 70% of patients screened for a TMVR trial are ineligible. “Because we are involved with trials of so many different devices, there’s a chance that if a patient doesn’t fit the criteria for one device, they will for another,” Dr. Krishnaswamy says.

Candidacy decisions must factor in the need for anticoagulation. All TMVR clinical trials require anticoagulation for three to six months. “These procedures are situations with high thrombotic risk, so most operators will continue anticoagulation indefinitely,” Dr. Krishnaswamy notes. “When a patient is intolerant of anticoagulation, we generally won’t recommend a TMVR device.”

Advertisement

Patients who don’t qualify for a TMVR trial at Cleveland Clinic may ultimately be offered M-TEER if it is feasible. “The result may be modest, but it will provide some functional benefit,” Dr. Krishnaswamy says. “These patients may ultimately have no good treatment option.”

Whether TMVR might be superior to M-TEER is unknown, but a head-to-head comparative study is being planned. “M-TEER is very safe and has less stringent anticoagulation requirements,” Dr. Kapadia notes. “That’s hard to beat.”

Cleveland Clinic interventional cardiologists have more than a decade of experience using TMVR to address degenerated prosthetic valves in patients considered at high risk for repeat surgical mitral valve replacement.

The first FDA approval of a TMVR system for valve-in-valve TMVR, also called MViV, came in 2017.

MViV carries a risk of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO) that occurs when a leaflet of the surgically placed valve is displaced during the procedure. “If there is enough space to park a new valve, there is the potential for LVOTO,” Dr. Kapadia says. “It’s a major limitation of MViV.”

In 2023, Cleveland Clinic interventional cardiologists and imaging specialists reported a procedure they developed to mitigate LVOTO risk in this setting. The procedure, known as CLEVE (Cleveland Valve Electrosurgery), involves perforating the base of the anterior mitral valve leaflet and dilating it with a balloon to separate it from the prosthetic valve frame. When the transcatheter valve is inserted in the space, it pushes the entire surgical leaflet away, creating a larger opening and preventing LVOTO (Figure 2).

Advertisement

A recent review of Cleveland Clinic’s initial clinical experience with CLEVE (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;18[6]:767-781) confirmed complete clearance of the leaflet in 100% of cases.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3925c70a-aa1c-42ec-891e-4d03e04af748/25-HVI-6845762CQD-TMVR-inset2)

Figure 2. Series of images showing the CLEVE procedure to facilitate MViV. (A) A catheter and wire (arrow) perforate the base of the surgical valve leaflet followed by inflation of a balloon in the leaflet (arrows in B and C) to separate the surgical leaflet from the valve frame (arrow in D). The valve is then positioned through the perforation (E and F) and deployed in place (G). Panel H shows post-placement flow from the left ventricle (LV) to the aorta (Ao) unimpeded by the surgical valve leaflet overhanging the open stent struts of the new valve (arrow).

Cleveland Clinic clinicians have found none of the currently developed TMVR devices suitable for MViV. Their valve of choice in this setting is one of the balloon-expandable valves from the SAPIEN 3 valve family used for transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Dr. Krishnaswamy was a co-author of a recent large U.S. registry study (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;18[11]:1454-1466) that found low reintervention rates at three years after MViV with these valves.

When an annuloplasty ring fails after surgical mitral valve repair, the choice is repeat surgery or valve-in-ring TMVR (MViR), an emerging alternative.

The utility of MViR was evaluated in a U.S. registry study of 820 patients who underwent the procedure with third-generation balloon-expandable TAVR valves from 2015 through 2022 (JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17[7]:874-886). Patients’ mean Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk score was 8.2%, and 78% were in New York Heart Association class III or IV. MViR was associated with significant reductions in MR and symptoms at one year but also with elevated valve gradients and a reintervention rate of 9.1%.

“MViR is reasonable in high-risk patients who cannot undergo surgery and who have appropriate anatomy for the procedure,” says Dr. Kapadia, who was a co-author of the study along with Dr. Krishnaswamy. “However, more study is needed to refine patient selection and best practices.”

Advertisement

“Patients with mitral annular calcification (MAC) and mitral stenosis alone or in combination with mitral regurgitation are an important group for treatment with TMVR devices,” Dr. Krishnaswamy notes. “Surgery in these patients can be very challenging, and perioperative and periprocedural morbidity and mortality rates are high.”

Cleveland Clinic has significant experience in transcatheter treatment of MAC and the use of TMVR trial devices in these patients. Preprocedural considerations include assessing the MAC distribution to determine if there is an adequate anchor for a prosthesis, careful annular sizing of the prosthetic valve and ensuring that the new LVOT will have adequate flow.

“Current options make this an exciting time to treat patients with mitral valve disease,” Dr. Krishnaswamy concludes. “Iterations of available devices, as well as new devices in clinical trials, will allow us to treat broader pathologies than we could previously. We are already treating patients we might not have been able to treat as effectively three to five years ago.”

Advertisement

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

And substudy reveals good outcomes with PASCAL system in patients with complex mitral valve anatomy

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Multimodal evaluations reveal more anatomic details to inform treatment