Uterine transposition cleared the field for radiation therapy

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/29975645-c127-4874-8511-e4fd58638ebe/uterine-transposition-7517459)

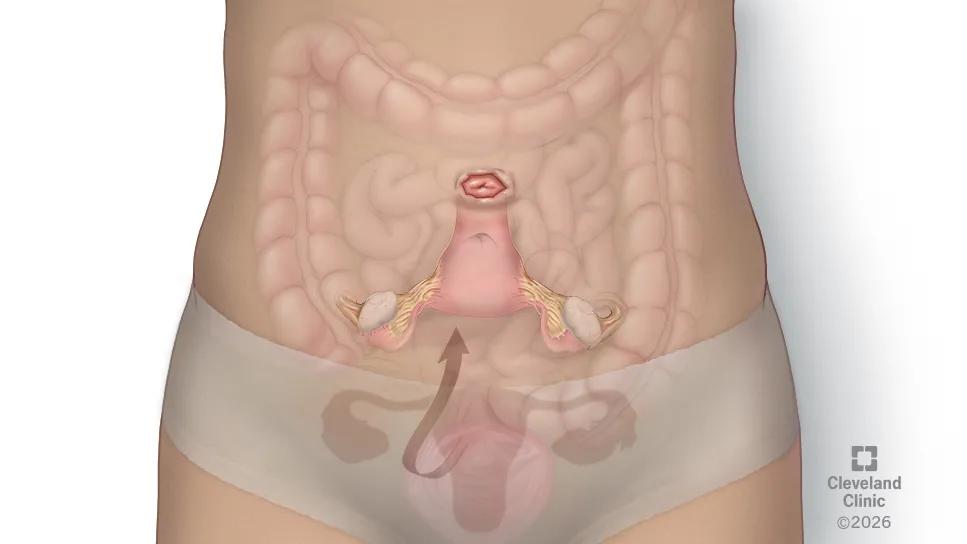

medical illustration of the repositioning of the uterus and cervix during transposition surgery

Technology can be a gift to patients experiencing infertility, but high out-of-pocket costs, as well as medical and legal complexities, can put certain interventions out of reach for many people.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

For women with pelvic cancers requiring radiation therapy, uterine transposition surgery can protect reproductive organs and preserve traditional childbearing options down the road.

Cleveland Clinic surgeons and specialists recently completed the health system’s first uterine transposition for a 30-year-old woman whose rectal cancer had not responded to chemotherapy. The case highlights the need for wider recognition of the technique and its potential, says surgeon Robert DeBernardo, MD, Gynecologic Oncology section head.

“I would like to see this operation become more common than it is,” says Dr. DeBernardo. “For someone with cancer who is interested in having children, it may avoid the need for extensive reproductive endocrinology.”

Oophoropexy (ovarian transposition), first used in the 1950s and eventually improved through laparoscopy, has become a common technique for protecting ovaries and preventing premature menopause for those receiving radiation treatment for certain pelvic cancers. While oophoropexy leaves open the possibility of retrieving eggs for in vitro fertilization, it doesn’t protect the uterus. Radiation destroys the endometrial lining and causes fibrosis, rendering the uterus inhospitable to implantation.

Advanced fertility techniques may address some of these hurdles but typically are not covered by medical insurance.

“In addition to having to create embryos, a gestational carrier is needed, both of which are quite expensive,” says Dr. DeBernardo. “I take care of young women with cancer all the time, and probably only 5% can actually take advantage of these technologies.”

Advertisement

At the time Dr. DeBernardo and partner Johanna Kelley, MD, treated their patient, the surgery had been done perhaps less than 30 times worldwide. In addition to being a first at Cleveland Clinic, it was the first done completely laparoscopically.

Before surgery, the team harvested eggs on the chance that the patient might develop ovarian failure. The operation itself lasted less than three hours, during which the team moved the patient’s uterus, cervix, fallopian tubes and ovaries high into the upper abdomen.

“We used indocyanine green to demonstrate adequate perfusion throughout the procedure so that we didn't compromise the blood supply to the ovaries or the uterus,” says Dr. DeBernardo. “We also used intraoperative fluoroscopy, and had people from the radiation oncology group take a look at our intraoperative imaging, to assure ourselves that we were putting the uterus well outside the irradiated field.”

The patient received a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist to temporarily stop ovarian function and decrease bleeding. During surgery, the team also delivered the cervix through the abdominal wall high on the abdomen to create a stoma, which prevents any fluids or mucous from seeping internally and creating a bowel obstruction.

The surgery proceeded smoothly and the patient lost only 25 CCs of blood. She spent the night at the hospital so the team could confirm that the ovaries were receiving normal blood flow. Her recovery went without complications, and she began radiation treatment two weeks later.

Advertisement

Enabling patients to proceed with radiation therapy quickly is an important factor, Dr. DeBernardo notes. After that regimen was complete, the transpositioning was reversed and the tumor resected during the same surgery.

“What’s advantageous about this procedure is that our patient will be able to conceive without intervention,” says Dr. DeBernardo. “She will need to deliver by C-section, but in the end she shouldn't need fertility services and she should be able to carry as many children as she wants.”

For clinicians with certain patients facing fertility-threatening cancers, uterine transposition should be considered, says Dr. DeBernardo. The procedure is still not widely known but is expected to be more common.

“It’s important that oncologists know about this new procedure because it will be a really good option for a small subset of patients,” he says.

Cleveland Clinic employs a multidisciplinary approach involving the surgeons, oncologists and radiation oncologists, as well as a reproductive endocrinologist. Dr. DeBernardo works closely with Mindy Christianson, MD, MBA, the health system’s Chief of Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility.

Patient are even less likely to know uterine transposition is an option, and may not even be thinking about future fertility, Dr. DeBernardo says. That’s why it is incumbent upon clinicians to start the conversation.

“We're seeing more and more cancer in younger women,” he says. “People are also tending to delay childbirth. In the midst of a cancer diagnosis, patients are often so overwhelmed that fertility may not be at the top of their mind. If we have an opportunity to help them avoid suffering unwanted consequences when they’re ready to build their family, we should do so.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Increasing uptake remains a challenge

Multidisciplinary teams work together in in-situ scenarios

ACOG-informed guidance considers mothers and babies

Prolapse surgery need not automatically mean hysterectomy

Artesunate ointment shows promise as a non-surgical alternative

New guidelines update recommendations

Two blood tests improve risk in assessment after ovarian ultrasound

Recent research underscores association between BV and sexual activity