Large Cleveland Clinic series underscores challenges of decision-making for this rare defect

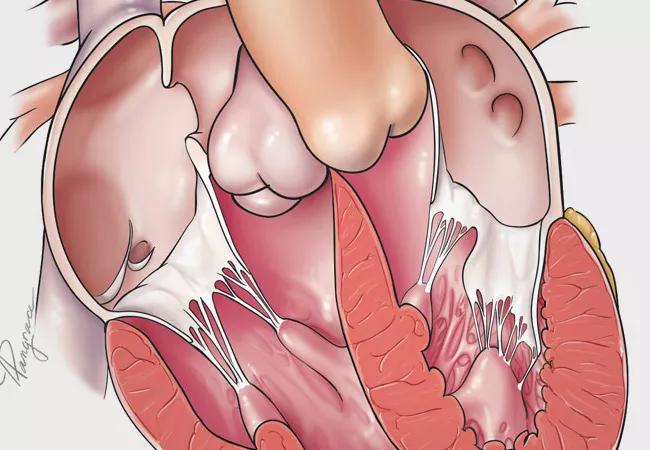

Patients with congenitally corrected transposition of the great arteries (ccTGA) who undergo early anatomic repair fare better than those who have physiologic repair, even with tricuspid valve interventions. That’s the lead finding among a group of insights from a Cleveland Clinic retrospective review of 240 patients with ccTGA that underscores the enduring complexity of this congenital heart defect.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The study, one of the largest and most wide-ranging series of ccTGA cases published to date, appears in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2021;161:1080-1093).

“Teasing out the best strategy for managing the extremely heterogeneous population with ccTGA poses enormous challenges,” says Cleveland Clinic pediatric and congenital heart surgeon Tara Karamlou, MD, MSc, corresponding author of the study. “This analysis, based on data from a large sample with long follow-up, does not provide a single best answer for every patient, but it can better inform decision-making for those faced with this rare anomaly.”

ccTGA is a rare defect — affecting 5,000 to 10,000 U.S. residents — that can present from birth to late adulthood. It is also associated with a wide variety of additional lesions, including ventricular septal defects, dextrocardia and valve abnormalities.

Treatment options include the following:

“Cleveland Clinic, with its large patient population and many decades of systematic clinical data collection, provides a good opportunity to glean best management practices for this condition,” says study co-author Hani Najm, MD, MSc, Chair of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery at Cleveland Clinic.

Advertisement

The investigative team retrospectively reviewed 240 patients diagnosed with ccTGA between 1955 and 2020; all but three were managed since 1983. Patients’ median age at presentation was 8.5 years, with the 15th and 85th percentiles at 0.38 and 41 years. Patients were categorized by intervention, as follows:

Additionally, 46 patients had their main procedure elsewhere before presenting to Cleveland Clinic and were not included in the analysis.

Patients were followed for a median of 10 years. Highlights of clinical outcomes include the following:

Advertisement

Dr. Karamlou notes that the difference in survival rates between the anatomic repair and physiologic repair groups was not statistically significant. However, she believes the trend is likely important and that the dataset may not have been large enough to demonstrate significance.

Drs. Karamlou and Najm identify several key takeaways from this study.

Early anatomic repair is the preferred strategy for the large majority of children. Physiologic repair is compromised by progressive right ventricular dysfunction, despite tricuspid valve interventions, with survival becoming impacted 12 years after the primary intervention.

Fontan procedures are viable options for select patients. Patients with a single atrioventricular valve (i.e., tricuspid atresia) or a single ventricle who were treated with a Fontan procedure had excellent midterm outcomes.

Tricuspid intervention among physiologic repair patients does not improve outcomes. The study found that it neither improved morphologic right ventricular function nor appreciably improved survival.

Optimal paradigms for pulmonary artery banding are still uncertain. Although the investigators reviewed echocardiographic data longitudinally with detailed image review, they were unable to define optimum criteria and gradient thresholds for pulmonary artery banding. They note that further defining this is especially important to help predict which patients will have maladaptive myocardial responses to afterload from a pulmonary artery band.

Nonintervention is a viable strategy. Evidence indicated that this group did well, partially because they could transition to other pathways when they “failed” expectant management.

Advertisement

“Identifying which patients can live their life without needing corrective surgery remains a challenge,” Dr. Najm notes. “A patient with a balanced anatomy and no evident dysfunction may be a good candidate for an expectant strategy.”

In an accompanying commentary on the study, pediatric cardiologist Joseph Clark, MD, of Penn State Children’s Hospital, observes: “Although anatomic repair has become a favored choice, and the supporting rationale is sensible, intuitive, and backed by accumulating experience, there remains some room for equipoise. As this study shows, there was no clear winner among the multiple treatment pathways for this complex and heterogeneous disease.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients