The progressive, nonspecific symptoms of subacute infective endocarditis can be subtle

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/9f03d098-7332-4678-a151-c080bc619698/Brown-infective-endocarditis-hero_jpg)

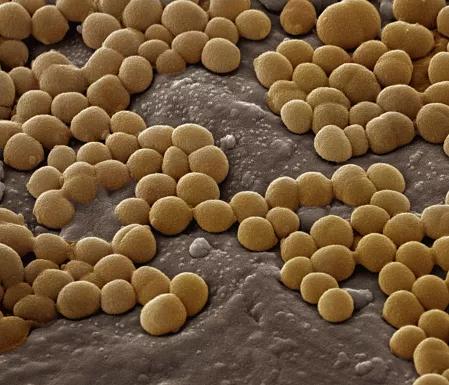

bacteria artwork

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A patient presents to the hospital with a 6-week history of malaise, oligoarticular asymmetric inflammatory arthritis, palpable purpura on lower extremities, acute kidney injury and the presence of red blood cell casts on urine microscopy. They also have a positive ANCA. Although it sounds like ANCA vasculitis, this is actually a great example of a patient with subacute infectious endocarditis (IE). Some clues to the diagnosis may be present, including fever, weight loss, normal platelets (usually high in active vasculitis) and low complements (usually normal in ANCA vasculitis). Although IE can look very similar to a small vessel vasculitis, the consequences of immunosuppressing this patient could be devastating.

Subacute infectious endocarditis can be subtle, presenting over months of progressive, nonspecific symptoms. Some patients may not even develop a fever. Rheumatologists should be aware of the ways IE can mimic systemic autoimmune conditions.

IE produces multiple complications, from embolic disease from valvular vegetations such as cerebrovascular accidents and splenic infarcts, to other manifestations that are not clearly secondary to embolism. The immune sequelae of endocarditis was first suspected when biopsy of Osler nodes — the well-known cutaneous manifestations of IE on the fingers and toes — demonstrated a sterile vasculitis. Further traction for the immune etiology of endocarditis-related sequelae came from a paper published in 1962 demonstrating many patients with endocarditis had low complement levels, and worse renal outcomes in patients with hypocomplementemia.1 Additional studies showed nearly all patients with IE develop circulating immune complexes, and the glomerulonephritis in many patients with IE have immune complex deposition demonstrated by immunofluorescence.2,3 It is hypothesized that immune complex deposition plays a role in multiple manifestations of IE including the peripheral joint involvement.

Advertisement

Approximately 30% of patients presenting with IE have articular manifestations, which can be divided into pyogenic and immunologic subtypes. The pyogenic causes of joint pain include direct infectious embolization from the cardiac vegetation into a joint or bone, causing osteomyelitis. Most commonly this occurs in the vertebrae and presents as an acute, focal back pain. Overall, focal vertebral osteomyelitis is the most common articular manifestation of IE. The inflammatory arthritis seen in the peripheral joints is most likely a result of immune complex deposition within the joint triggering monoarticular or asymmetric oligoarticular inflammatory arthritis. The synovial fluid is often mildly inflammatory, almost always sterile and resolves rapidly with the initiation of antibiotic therapy.4 The peripheral joint involvement of IE is non-destructive, again arguing against a direct infectious process in the septic joint.

IE can mimic small vessel vasculitis in a variety of ways, including palpable purpuric rash, inflammatory arthritis, digital ischemia and glomerulonephritis. To further confuse matters, IE can also be associated with positive ANCA serologies as well as positive serum cryoglobulins.5,6,7 Renal histology can provide insight, as many patients with endocarditis develop an immune complex glomerulonephritis in contrast to the typical pauci-immune glomerulonephritis of ANCA vasculitis; however, pauci-immune glomerulonephritis can also be seen in a subset of subacute bacterial endocarditis that is indistinguishable from ANCA vasculitis. Because of the similarities of small vessel vasculitis and IE, ordering a set of blood cultures in acute presentations of ANCA vasculitis is critical to rule out important infectious mimics as much as possible.

Advertisement

Multiple autoimmune serologies and rheumatologic tests can be positive in patients with IE. Rheumatoid factor is positive in nearly half of patients with IE, which can be tricky as joint manifestations can be an early complaint in patients with IE.1 Nearly 97% of patients with IE have measurable immune complexes. Immune complex formation is not unique to IE as it is common in autoimmune conditions and in other infections — including sepsis — but the rates of immune complex in IE seem to be much higher than other infections. Rheumatologists do not typically measure immune complexes in patients, but the downstream consequences of immune complex formation and deposition can be seen in IE with low serum complement levels.1 In fact, in a patient with suspected ANCA vasculitis, low complement levels can be a clue that IE is the culprit.

Subacute bacterial endocarditis can present with a broad range of symptoms including many that mimic systemic autoimmune diseases. Patients with IE can present with joint pain and may have a positive rheumatoid factor. IE can present with multiple components of a small vessel vasculitis and again have positive ANCAs and serum cryoglobulins. Rheumatologists see many conditions that do not quite fit into a proper category of a systemic autoimmune disease and should have a low threshold for checking blood cultures.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Researching the biological basis for why treatment is or is not effective

Scribing system helps create more face-to-face interactions

A conversation with Leonard Calabrese, DO

The case for continued vigilance, counseling and antivirals

High fevers, diffuse rashes pointed to an unexpected diagnosis

No-cost learning and CME credit are part of this webcast series

Summit broadens understanding of new therapies and disease management

Program empowers users with PsA to take charge of their mental well being