Treatment for scleroderma can sometimes cause esophageal symptoms

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5c9a990e-43d3-4799-bb68-d4366a66c0d9/23-RHE-4333862-CQD-650x450-1_jpg)

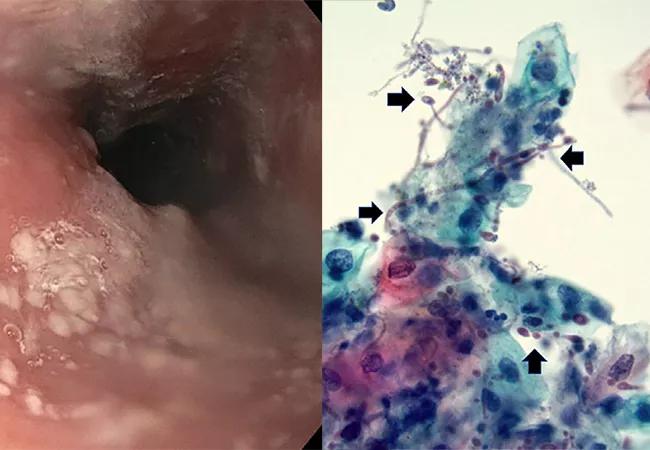

esophageal plaques

By Soumya Chatterjee, MD, MS, Tarik M. Elsheikh, MD, and Donald F. Kirby, MD, FACP

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 68-year-old woman with a 20-year history of systemic sclerosis suffered from chronic iron-deficiency anemia and required multiple iron infusions and packed red blood cell transfusions. Repeated upper endoscopies had shown active gastric antral vascular ectasias, a known complication of systemic sclerosis that causes chronic gastric blood loss.

She had undergone intermittent upper endoscopic ablation using argon plasma coagulation to control the persistent blood loss from gastric antral vascular ectasias. In addition, she needed pantoprazole 40 mg twice daily to control her acid reflux symptoms adequately. During her recent upper endoscopy for routine argon plasma coagulation, she was found to have localized white plaques in the middle third of the esophagus that could not be washed away with water irrigation. On microscopy of the brushings from the white plaques, fungal organisms morphologically consistent with Candida species were detected.

Fungal cultures grew Candida albicans. Based on the patient’s reduced creatinine clearance, she was treated with oral fluconazole 100 mg daily for two weeks, followed by nystatin suspension 500,000 units swish and swallow prior to bedtime for three months.

Esophageal involvement in scleroderma can manifest as dysphagia (esophageal dysmotility), gastroesophageal reflux disease, odynophagia (ulcerative esophagitis), pill esophagitis, esophageal stricture, Barrett’s esophagus, and rarely, adenocarcinoma.1 Long-term proton pump inhibitor use is recommended in scleroderma patients, as esophageal dysmotility and lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction usually lead to gastroesophageal reflux disease and can result in the above complications.1 However, it may not be commonly known that long-term proton pump inhibitor use

is also a risk factor for esophageal candidiasis.2.3

Advertisement

Most cases of esophageal candidiasis are asymptomatic and incidentally discovered during an upper endoscopy performed for another reason, such as in this case.3 However, sometimes patients develop odynophagia, dysphagia and retro sternal pain.3 Esophageal ulceration and stenosis are rare.3

Other risk factors for esophageal candidiasis include human immunodeficiency virus infection, diabetes mellitus, smoking, glucocorticoid use, antibiotic use, esophageal achalasia, malignancy, radiation therapy, atrophic gastritis, advanced gastric cancer and gastrectomy.2

Diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis requires either cytology of brushing or biopsy of the white plaques seen on esophagoscopy, the former being more sensitive.4 Cytology demonstrates the fungal elements of Candida species. Fungal cultures confirm the diagnosis, help determine the Candida species, and allow antifungal susceptibility testing. Conversely, a mucosal biopsy is required to diagnose other etiologies of white esophageal plaques, such as epidermoid metaplasia, eosinophilic esophagitis and esophagitis dissecans superficialis.

During the passage from the oral cavity to the esophagus, the brush is protected by a sheath, eliminating the possibility of contamination by oral Candida. Systemic antifungal treatment is necessary to prevent complications such as esophageal stricture formation or perforation; for example, oral fluconazole, 200-400 mg daily for 14 to 21 days.5

However, the dose needs to be adjusted for impaired renal function.5 Also, drug-drug interactions may affect therapy. If oral therapy is not tolerated, intravenous fluconazole, an echinocandin, or even amphotericin B can be used.5

This case provides evidence that occasionally, an esophageal problem in a scleroderma patient can be caused by their treatment, not their disease.

Advertisement

Top left image: Upper endoscopy shows localized white plaques in the middle third of the esophagus that could not be washed off with water irrigation. Top right: A cytologic examination revealed benign squamous cells and occasional neutrophils. There were numerous admixed fungal spores and pseudohyphae (arrows) staining red, morphologically consistent with Candida spp.

This article was originally published in The American Journal of Medicine, Vol 136, No 8, August 2023.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

Despite less overall volume loss than in MS and NMOSD, volumetric changes correlate with functional decline

It’s time to get familiar with this emerging demyelinating disorder

From dryness to diagnosis

Early experience with the agents confirms findings from clinical trials

Despite advancements, care for this rare autoimmune disease is too complex to go it alone

Patient’s symptoms included periorbital edema, fevers, weight loss

Could the virus have caused the condition or triggered previously undiagnosed disease?