Cleveland Clinic study finds expected STS risk no longer reflects current outcomes

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e44a405c-77dd-44c2-b60d-fcc098aee5df/23-HVI-3836208-surgical-aortic-valve-replacement-650x450-1_jpg)

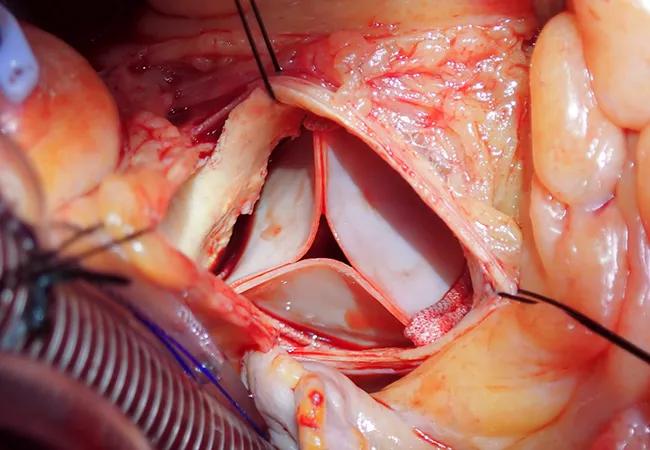

implanted bioprosthesis for aortic valve replacement

The operative risk of contemporary surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) at high-volume centers is overestimated by current Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) risk models, conclude Cleveland Clinic researchers based on a retrospective study of a large series of isolated SAVR operations at their institution.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“The outcomes we observed improved over time while the expected risk remained flat,” says the study’s senior author, Lars Svensson, MD, PhD, Chair of Cleveland Clinic’s Miller Family Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute. “These results call for development of risk models that are more agile and better reflect the variability seen in current practice.”

The study, which was published in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2023;165:591-604), also demonstrated that SAVR provided durable survival benefit in low-risk patients, “supporting early surgery and providing a benchmark for transcatheter AVR,” the investigators write.

Indications for transcatheter AVR (TAVR) now include patients at low operative risk from AVR surgery, and recent randomized trials have demonstrated positive outcomes of TAVR in this population. These developments, together with advancements in TAVR device technology and improvements in echocardiography to guide timing of TAVR in asymptomatic patients, have driven uptake of TAVR for patients at low surgical risk.

Yet over the same time period, the study authors note, SAVR has likewise undergone improvements in technique and safety — but perhaps with less attention. “We suspected that, as a result, STS prediction models might be overestimating the risk of SAVR mortality and morbidity, especially for high-volume centers,” Dr. Svensson says.

This prompted him and colleagues to evaluate outcomes after SAVR in patients with STS predicted risk of mortality (PROM) scores of less than 4%. “This mirrors the definition of ‘low risk’ used in the randomized TAVR trials, with key exceptions such as bicuspid aortic valve disease,” Dr. Svensson explains.

Advertisement

They identified all adults with an STS PROM score < 4% who underwent isolated SAVR at Cleveland Clinic’s main campus from January 2005 to January 2017 — 3,474 patients in all. They then compared observed mortality and composite major morbidity or mortality against STS expected outcomes according to the year the operation took place. Time-related mortality was also tracked.

The observed operative death rate across the study period (0.43%) was substantially lower than the STS expected rate (1.6%), yielding an observed-to-expected mortality ratio of 0.27 (95% CI, 0.14-0.42). Observed-to-expected ratios were 0.65 for stroke (95% CI, 0.41-0.89) and 0.50 for reoperation (95% CI, 0.42-0.60).

Lower-than-expected mortality was seen both in the lowest-risk patients (those with PROM scores < 1%) and in patients with PROM scores of 3% to 4%. Overestimation of risk was greatest for patients at the upper end of the PROM range.

Moreover, the probability of major morbidity or mortality declined consistently throughout the study period, from 8.6% in 2006 to 6.7% in 2011 to 5.2% in 2016. During this period, the expected risk remained relatively constant, despite increasing use of TAVR at Cleveland Clinic.

Logistic regression analysis showed that several factors were associated with increased risk of major morbidity or mortality: higher mitral valve regurgitation; ventricular hypertrophy; pulmonary, renal and hepatic failure; coronary artery disease and an earlier date of surgery.

Across the cohort, post-SAVR survival was 98% at one year, 91% at five years and 82% at nine years. “These survival rates are superior to those for the general U.S. population when matched for age, race and sex,” Dr. Svensson notes. “They illustrate a durability of benefit that lends support for early intervention and can serve as a valuable comparator as data accumulates on the durability of TAVR in younger patients.”

Advertisement

The researchers conclude that SAVR outcomes in low-risk patients have improved over time and that expected risk no longer reflects contemporary outcomes, at least not at a high-volume center. They note that a similar discrepancy between expected and actual outcomes has been detected in studies of TAVR as well.

“These results for SAVR and TAVR suggest that there is substantial variability in clinical outcomes among institutions and operators,” the study authors write. “It is important to differentiate average outcome probabilities across the nation from those that are achievable in centers of excellence.”

They emphasize that this does not mean volume is the sole contributor to outcomes, noting that Cleveland Clinic adopted a series of process improvements for aortic valve disease care beginning around 2008. These iterative changes included, among others, standardization of preoperative screening and imaging protocols, refinement of intraoperative pump and cardioplegia protocols, adoption of a checklist prior to chest closure to reduce postoperative bleeding and creation of early extubation protocols.

“A distinction should be made between generalizable results — meaning achievable at most institutions performing SAVR — and repeatable results — meaning achievable at institutions willing to make alterations” in practice patterns and institutional culture, the researchers write. They add that most of the process changes made at Cleveland Clinic can be adopted at other centers, and many have been.

Advertisement

The authors note that their findings support development of a more agile, “real-time” risk prediction tool. “Optimal counseling on the most appropriate valve therapy for individual patients requires continuously updated risk models that reflect state-of-the-art care,” says Dr. Svensson. “Patients deserve to know not only what a typical outcome is but also what is potentially achievable to minimize their risk.”

These sentiments are echoed by Cleveland Clinic Cardiovascular Medicine Chair Samir Kapadia, MD, who was not among the study authors. “In the current era when many centers are offering aortic valve replacements, including SAVR and TAVR, it is important for patients to have benchmark data like these from high-volume excellent operators, to inform them of their treatment options,” says Dr. Kapadia. “Although randomized trials provide comparative data, there is tremendous variability in outcomes and patient selection among different U.S. centers. It is important for patients to understand these differences before making treatment choices.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Experience-based takes on valve-sparing root replacement from two expert surgeons

30-year study of Cleveland Clinic experience shows clear improvement from year 2000 onward

Surgeons credit good outcomes to experience with complex cases and team approach

For many patients, repair is feasible, durable and preferred over replacement

In experienced hands, up to 95% of patients can be free of reoperation at 15 years

Experience and strength in both SAVR and TAVR make for the best patient options and outcomes

Ideal protocols feature frequent monitoring, high-quality imaging and a team approach