How and why to tell the difference

by Emily Littlejohn, DO, MPH, and Cassandra Calabrese, DO

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 22-year-old female with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is being evaluated for leukopenia with predominant lymphopenia. Her lupus has manifested with pericardial effusions, thrombocytopenia and lupus nephritis, and she is on hemodialysis. Her serologies show positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA), positive anti-double stranded DNA (dsDNA) and hypocomplementemia. In 2017, she started azathioprine 50 mg daily, which was increased to 100 mg several months later, along with hydroxychloroquine. She has had several infectious complications including line-related bloodstream infections. In March 2017, her white blood cell count (WBC) was 5.14 cells/m3 with absolute lymphocytes 1.24 cells/m3. In August 2017, her WBC remained stable while lymphocytes fell to 0.62 cells/m3; this level has waxed and waned, as low as 0.23 cells/m3. She now presents with worsening fatigue and increased arthralgias.

This case exemplifies the conundrum of leukopenia in SLE: is the leukopenia caused by underlying SLE activity? Or perhaps by her SLE treatment? An infection? Or a combination of factors?

Rheumatologists are no strangers to leukopenia, as they monitor complete blood counts (CBCs) daily to analyze the inner workings of the immune system, the absolute number of peripheral cells and the functioning or response of the bone marrow and thymus. The differential for leukopenia in a patient with autoimmune connective tissue disease includes underlying disease activity, medications, side effects and infection.

Advertisement

Leukopenia can be an important reflection of disease activity, occurring in almost half of patients with SLE. In fact, the American College of Rheumatology and the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics include leukopenia in the classification criteria for SLE.

Although the majority of white blood cells are neutrophils, leukopenia can reflect a total decrease in neutrophils or a selective reduction in lymphocytes. Studies have shown that T and B cells correlate with clinical lupus disease activity and treatment. More specifically, a relative and absolute decrease in T lymphocytes has been found in active lupus with the absolute number of B cells decreased to a lesser extent. Another study showed correlation of antilymphocyte antibodies with lymphopenia in active SLE, thus demonstrating a clear association of increased antilymphocyte antibody activity and SLE exacerbation.

Many factors have been suggested to play a role in decreased peripheral neutrophils in SLE, including neutralizing autoantibodies against growth factors that act on neutrophils, bone marrow suppression, autoantibody-driven cell removal and death by NETosis. One study showed that SLE serum stimulated oxygenation activity when incubated with normal neutrophils based on a chemoluminescence (CL) response. Interestingly, the percent CL response correlated with other measures of disease activity in SLE blood such as dsDNA antibodies and complement component 1q- (C1q) binding immune complexes (IC). The implications of this work are twofold: IC-driven neutropenia is related to underlying SLE activity and can increase susceptibility to infection.

Advertisement

Of all the immunosuppressive therapies used to treat SLE, glucocorticoids (GC) carry the strongest associated risk of infection. GC have numerous effects on various WBC populations, as they function mainly by interfering with access of neutrophils and macrophages to sites of inflammation. Within four to six hours of administration, GCs cause a neutrophilic leukocytosis due in part to accelerated release from bone marrow, followed by a transient lymphopenia, mainly due to redistribution out of circulation.

Lymphopenia and GC use are known risk factors for infections in SLE patients. In a single-center retrospective study of incidence of pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP), Godeau et al reported 34 cases over 10 years, of which 94 percent were receiving GC and 91 percent were lymphopenic (< 1.5×109) at the time of PJP diagnosis. Lymphopenia has been observed in several other studies in SLE patients with PJP. Experts recommend PJP prophylaxis in SLE patients receiving prednisone ≥ 30 mg daily.

Azathioprine (AZA) is a prodrug which depresses bone marrow function in a dose-dependent fashion, with increasing effects over time. With chronic administration, development of megaloblastosis may precede worsening cytopenias. Because the immunosuppressive properties of AZA are mainly achieved by cytotoxic effects on T lymphocytes, some degree of lymphopenia can be interpreted as medication efficacy rather than an adverse event.

Another prodrug, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), causes decreased B- and T-cell proliferation with variable frequencies of leukopenia.

Advertisement

Cyclophosphamide (CYC), also a prodrug, is sometimes given to induce a goal leukocyte count of 2 to 3 k/uLs. Similar to AZA mechanistically, this lowered count is an anticipated and expected drug effect that can reflect appropriate (therapeutic) immunosuppression.

The important clinical question is if the associated cytopenias from use of this medication portend a significant infectious risk. Much of the data to shed light on this question comes from the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) population, where azathioprine is widely used. In one study of a large IBD cohort, 385 patients were on AZA, with 100 cases of lymphopenia (defined as < 1,500 lymphocytes/μl). Of these 100 cases, nine patients had opportunistic infections. Infections were not significantly more frequent in the subgroup with the lowest nadir between 200 and 499 C/μl than in the group with counts at 1,000 to 1,499 C/μl. In fact, opportunistic infections were not observed in the patient group with severe lymphopenia (< 200 C/μl).

These findings are in contrast to a study examining 97 patients with chronic inflammatory diseases receiving methotrexate, AZA or CYC with or without GC. Total lymphocyte counts were markedly decreased in patients receiving GC at doses > 10 mg prednisolone equivalent per day, or combination immunosuppressive therapy with cytotoxic drugs and GC at various doses. T-helper lymphocyte count < 250/µl best predicted subsequent hospitalizations for infections, suggesting that low T-helper cell counts, regardless of their pathogenesis, can predict infections.

Advertisement

There are numerous infectious causes of cytopenias. Viral infections known to cause leukopenia include Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus and human immunodeficiency virus, to name a few. Parvovirus B19 classically causes aplastic anemia in immunocompromised patients; however, it can also cause symptoms (fever, arthralgia) that resemble a lupus flare, and rarely can cause pancytopenia, further complicating the patient assessment.

We ultimately determined that an underlying lupus flare caused our patient’s lymphopenia, rather than her immunosuppressive regimen or an infection. She was admitted to the hospital and obtained high doses of steroids for serositis. She clinically improved, and her lymphopenia also improved, despite continued use of azathioprine.

This case exemplifies the complexities faced when differentiating among infection, medication effect and lupus activity. It is important for physicians to understand that leukopenia, regardless of cause, will increase risk of infection, and that in many cases, there is high likelihood of both autoimmune and infectious processes occurring concomitantly. When dealing with leukopenia in this setting, a heightened awareness of the risk of infection, close monitoring of complete blood counts while on high-risk medication, and thorough evaluation for disease activity are crucial.

Dr. Littlejohn is associate staff in the Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases. Dr. Calabrese is associate staff in the Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Disease, holds a joint appointment in the Department of Infectious Diseases and is board certified in rheumatology and infectious diseases.

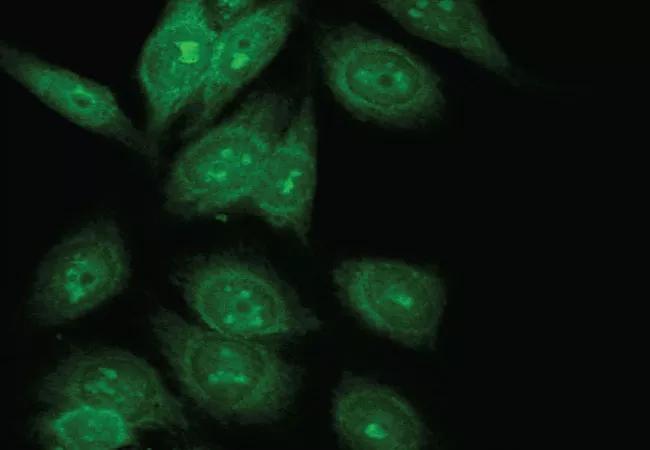

Feature image: Anti-nuclear antibody indirect immunofluorescence staining showing a nucleolar pattern.

Advertisement

The case for continued vigilance, counseling and antivirals

High fevers, diffuse rashes pointed to an unexpected diagnosis

No-cost learning and CME credit are part of this webcast series

Summit broadens understanding of new therapies and disease management

Program empowers users with PsA to take charge of their mental well being

Nitric oxide plays a key role in vascular physiology

CAR T-cell therapy may offer reason for optimism that those with SLE can experience improvement in quality of life.

Unraveling the TNFA receptor 2/dendritic cell axis