Resourcefulness is the rule to customize solutions for patient progress

By Richard Aguilera, MD, and Mary Stoffiere, MA, CCC-SLP

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 32-year-old man was transferred to a Cleveland Clinic inpatient rehabilitation hospital from a long-term acute care hospital. Until two months previously, he had been a healthy student, pursuing graduate-level engineering studies in Ohio. At that time, a pontine hemorrhage left him with aphonia, dysphagia and quadriplegia. He was on multiple antibiotics due to ventilator-associated pneumonia. He arrived with a tracheostomy tube, a percutaneous gastrostomy tube and a Foley catheter in place.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4e7ec1b8-41f4-42e9-86c7-7c40b1679cad/IMG_1917_jpg)

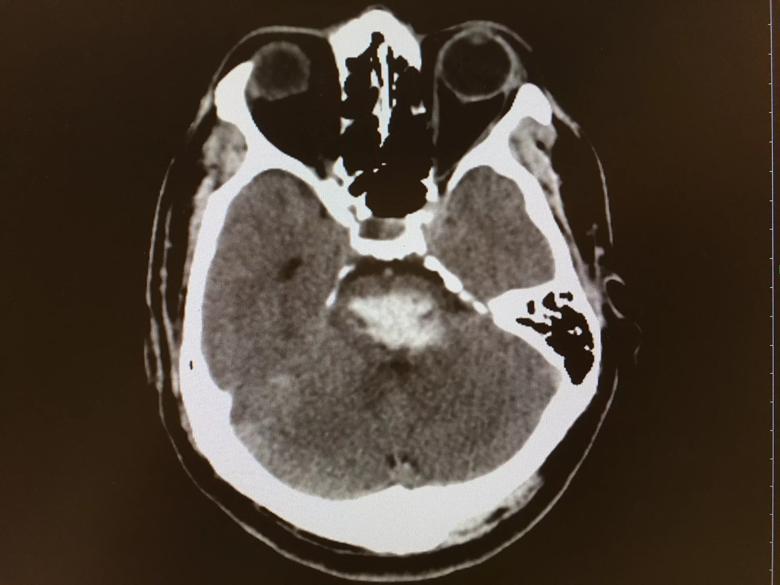

Axial head CT of the patient showing pontine hemorrhage.

As he improved medically, he was decannulated and continued respiratory therapy with breathing exercises. Nutritional support was provided and monitored. He was brought to the rehab hospital’s gym daily for physical and occupational therapy, emphasizing neuromotor re-education to facilitate recovery and maintain range of motion of his extremities. Transfer techniques were practiced, as was assisted wheelchair mobility.

After several attempts at communication, we broke through by asking him to use eye blinks (one blink for “yes”, two for “no”) to signal responses to simple questions. He was then diagnosed with locked-in syndrome, a rare condition in which patients are conscious and aware but cannot communicate because of paralysis and inability to speak.

Locked-in syndrome most often results from ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke affecting the corticospinal, corticopontine and corticobulbar tracts. It can also be caused by trauma, tumors, myelinolysis, toxins or heroin abuse.

Advertisement

Often the ability to blink and move the eyes is preserved, sometimes along with control of facial and neck muscles, offering the only potential avenues of communication. Some patients can change facial expressions or move the head or tongue.

Trying to make contact frequently is warranted, even after a period of months: It is common for patients to tire easily, and a short attention span is typical, especially soon after the injury.

Using eye-blink yes/no communication, we could better assess him by asking sequentially if he had pain, dizziness, nausea, etc. It also enabled our care team and visitors to ask if he wanted to listen to music or an audiobook to provide mental stimulation.

Our team and the patient’s family quickly moved on to spelling words, by having him blink for each desired letter as the questioner recited the alphabet. Morse code can also be used, using long and short blinks for dashes and dots.

But eye-blink communication techniques are slow and cumbersome for patient and caretakers alike. Our patient clearly could benefit from moving beyond them.

Fortunately, a number of high-tech tools are now available for the severely disabled. Our occupational and speech therapy teams kicked into high gear, researching a number of technologies and working with local university bioengineering departments to identify the best fit for our patient.

We have found that not all devices work for every patient. One alternative communication device tracks gaze as a person focuses on letters, words or icons on a computer screen and then types out results or serves as a speech-generating device. This tool showed promise, but it caused our patient to fatigue quickly and develop nystagmus that persisted for hours. Next, we tried NeuroNode (see photo), a small wireless EMG device that translates electrical activity from a working muscle to operate an iPad or computer, allowing communication and independent computer use. Placed on a forehead muscle that our patient could consciously activate, it worked much better.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/7b4277e2-671a-4703-badb-117ee2ea4421/0914181658_HDR_jpg)

The NeuroNode EMG assistive technology device that was placed on the patient’s forehead muscle for communication.

We also used a Passy Muir® Valve, a one-way speaking valve that allows airflow past the vocal folds and into the oral cavity. While the patient was not able to generate intelligible speech, he was able to produce volitional sounds that allowed him to get the attention of his family and caregivers. The Passy Muir Valve also supports decannulation

We similarly explored ways to help our patient navigate the world with more independence. We obtained a power wheelchair operated by controls connected to a head array that allowed him to control speed and direction with the minimal neck movement that he retained. By discharge, he was motoring down the hospital corridors with a look of delight in his eyes.

High-tech gadgets are pricey and quickly become obsolete, so there is no sense in acquiring a closetful of devices to collect dust. Customizing a search for each patient is preferable. Some devices can be rented while you try them, and manufacturers will often offer in-house training to staff and patients on their use.

Family members should be continuously involved as much as possible to communicate, learn day-to-day care and develop long-term plans. Our rehab team worked closely with the patient’s family so that they were comfortable using the communication techniques established in the hospital and could transfer the patient to and from his chair and drive it when he tired.

Advertisement

It is especially critical that a patient’s eventual caretakers are motivated to keep the patient moving forward after discharge, by practicing gains, learning new skills as the patient is able and searching for advances as new technology becomes available.

After one month of inpatient rehabilitation, the patient was deemed ready for discharge, and the team assisted with arrangements to successfully place him home.

Rehabilitation of patients with locked-in syndrome is a tremendous challenge that few centers are equipped to undertake. A multidisciplinary rehabilitation team is essential, as is an ongoing management strategy that includes the following objectives and components:

Despite the grave disability of patients with locked-in syndrome, they can be helped. Although many patients regain some function over time, most remain chronically locked in or severely impaired. Clinicians must always be mindful that these patients are often cognitively intact with normal memory and thought processes. It is a continual challenge for the medical support team and caretakers to help patients feel connected to others and their environment, and to enable them to live out their lives with a level of mental richness approaching what they enjoyed before.

Advertisement

Dr. Aguilera is a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician in Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Ms. Stoffiere is Regional Director of Rehabilitation, Select Medical Inpatient Rehabilitation Division.

Advertisement

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges