Interventions abound for active and stable phases of TED

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/e3d1e896-b457-438f-b987-d3a4105152ed/23-EYE-4215262-CQD-Thyroid-eye-disease-tips-general-ophth-hero_jpg)

23-EYE-4215262-CQD-Thyroid-eye-disease-tips-general-ophth-hero

Thyroid eye disease (TED) has many names: Graves’ ophthalmopathy or orbitopathy, dysthyroid ophthalmopathy, malignant or endocrine exophthalmos, and thyroid-associated or -related orbitopathy. Patients have varied clinical presentations, and there’s no way to identify which patients will have more severe TED.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“It’s an autoimmune disorder with a loose association between the thyroid and periorbital region,” explains Catherine Hwang, MD, an oculofacial plastic surgeon at Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute. “The pathogenesis is not completely understood, which is why TED is one of the most difficult diseases I treat.”

There are two types of TED:

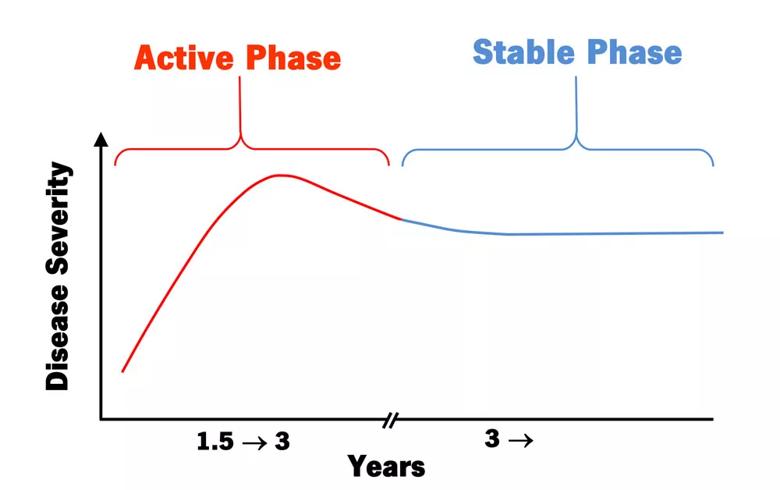

“I try to educate my patients that the active phase of TED can be around 18-36 months,” says Dr. Hwang. “During this time, they could have some improvement but usually won’t completely return to baseline. After the active phase, patients enter a stable phase, when corrective surgery becomes an option.”

Active TED “can feel like an eternity to patients,” says Dr. Hwang. “It’s important to support patients as they ride the emotional roller coaster of the disease.”

Medical interventions used early in the disease may help curb severity. Main goals during the active stage are to:

1. Establish a euthyroid state by working with the patient’s endocrinologist. If medications aren’t effective, Dr. Hwang recommends thyroidectomy rather than radioactive iodine.

2. Help patients stop smoking. “Most of my patients with severe TED are smokers,” says Dr. Hwang. “We always try to help our patients with smoking cessation as we know it can help prevent worsening of TED.”

Advertisement

3. Treat dry eye and exposure symptoms, the primary complaint in many patients with TED. In addition to conservative treatment with artificial tears and plugs, a small lateral tarsorrhaphy can reduce retraction of the upper eyelid and symptoms of exposure keratopathy. Hyaluronic acid fillers also can be used in the levator plane, transconjunctivally, to help with lid retraction. Fillers act like a gold weight and stretch the levator muscle. Botulinum toxin also can be used.

4. Follow patients regularly. “If the disease is more severe, I see the patient more often; if it’s less severe, I see them less often,” says Dr. Hwang. “At each visit I take measurements, but I also consider how the patient feels: the same, better or worse. If they feel worse or have worsening symptoms, we consider immunosuppression.”

5. Consider immunosuppression. Intravenous methylprednisolone (500 mg per week for six weeks, then 250 mg per week for six weeks) is the first-line treatment to reduce inflammation and help patients feel better. It doesn’t address fibrosis, however, and is not recommended for patients with hepatic, renal, cardiovascular or psychiatric disease or uncontrolled diabetes. Other immunotherapies are being studied, including IL-6 receptor antibodies and insulin-like growth factor receptor antibodies such as teprotumumab.

6. Consider orbital radiotherapy, which may have some effect on inflammation, motility and proptosis. It is administered in 10 treatments over two weeks (total 20 Gy) and produces minimal side effects (e.g., corneal dryness, cataracts).

Advertisement

7. Consider orbital decompression in cases of optic neuropathy. Optic neuropathy affects approximately 5% of patients with TED, including some without significant proptosis. Patients who smoke or have diabetes are at highest risk. Intravenous methylprednisolone is often the first-line treatment. If inflammation does not decrease, medial decompression surgery may help create more space for the optic nerve.

Although patients can be eager to return to their normal eye function and appearance, surgery should not be considered (unless for optic neuropathy) until TED stabilizes.

“Performing decompression, eyelid surgery or eye muscle surgery too soon could be detrimental,” says Dr. Hwang. “During the active phase of TED, things are continually changing and sometimes improve on their own. In addition, early surgery could trigger a reactivation of the disease.”

Remember Rundle’s curve, she advises (Figure 1). Lid retraction resolves in 57% of patients. Extraocular muscle involvement remains stable in 50%, worsens in 25% and improves in 25%. Following a period of maximum severity, proptosis tends to abate and stabilize.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/14afdfe7-a5a7-491d-ad00-58a3def6ecc1/23-EYE-4215262-CQD-Thyroid-eye-disease-tips-general-ophth-chart_jpg)

Figure 1. The Rundle’s curve concept illustrates how severity of TED increases during the early phase of disease and stabilizes during the later phase.

“When it’s time to consider surgery, I try to help patients set realistic expectations,” says Dr. Hwang. “Patients likely won’t return to how they looked before TED, but we strive to improve their quality of life and help them feel better. I stress that surgery is for the health of their eyes, but of course we also think of cosmesis with every surgery.”

Surgical treatment often requires multiple steps.

Advertisement

Step 1: Decompression. Decompression surgery involves removing bone or intraconal fat in patients with proptosis, pressure pain, congestion, exposure or optic neuropathy.

Decompression procedures are customized for each patient according to the severity of proptosis; the size of the lacrimal gland, lateral sphenoid and medial rectus; and other factors. Dr. Hwang usually obtains an orbital imaging study, such as a CT scan, to evaluate the patient’s anatomy. Then, to access the desired locations for decompression, she recommends one or more surgical approaches: lateral eyelid crease, transconjunctival or transcaruncular (Figure 2).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a24b1756-5aa9-49b6-89d9-a34ecfa15d7d/23-EYE-4215262-CQD-Thyroid-eye-disease-tips-general-ophth-illustration-341x1024_jpg)

Figure 2. Three approaches to decompression surgery for TED: lateral eyelid crease (top), transconjunctival (middle) and transcaruncular (bottom).

Lateral eyelid crease decompression is best for patients with large lacrimal glands and prominent brow fat. The goal of surgery is to remove the thicker bone in the lacrimal area as well as the sphenoid diploe, creating more room for the orbital contents.

The lateral transconjunctival approach is best to avoid a lateral eyelid crease incision and gain access to the thick lateral bone, especially useful in Asian patients. It’s also useful for patients with less proptosis or those with more congestion than proptosis.

The transcaruncular approach often provides the most proptosis reduction. According to Dr. Hwang, the procedure is best for patients with significant proptosis. The surgeon can access the medial wall and open it into the sinuses. Caution is taken in patients with larger medial rectus muscles. These muscles can fall into the sinus and cause worsening diplopia, but patients are counselled to be prepared for this risk.

Advertisement

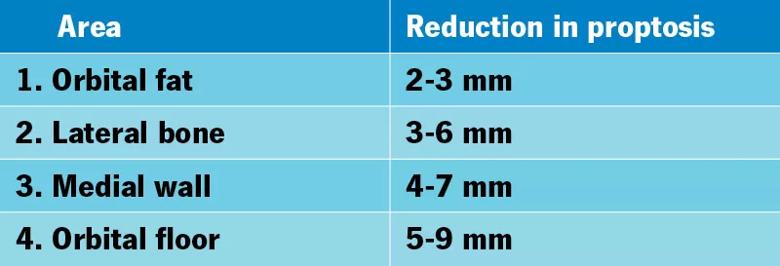

Orbital decompression progresses in a graded fashion (Table), beginning with orbital fat and adding the lateral bone and medial wall if needed for more reduction. Rarely is the orbital floor used for decompression as surgery there can cause setting-sun eye phenomenon and infraorbital nerve damage.

Balanced lateral and medial decompression is useful in patients with severe proptosis. However, patients may have worsened diplopia postoperatively.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/36656c45-876e-459e-bc3b-c0231bc1cb61/23-EYE-4215262-CQD-Thyroid-eye-disease-tips-general-ophth-table_jpg)

Table. Stages of orbital decompression.

Step 2: Eye muscle surgery. Some patients require eye muscle surgery primarily to correct diplopia in primary vision and downward gaze. Eye muscle or strabismus surgery is performed after decompression surgery as decompression surgery could affect diplopia.

Step 3: Eyelid repositioning. Upper eyelid retraction surgery can be performed either posteriorly or with a full-thickness blepharotomy. Posterior release may provide a longer tarsal platform show, while full-thickness blepharotomy may help better adjust lid crease height. The approach depends on the surgeon as well as the amount of retraction.

In the lower eyelid, release of the retractors can be performed alone or with a hard palate or other graft, with or without a mid-face lift depending on the patient’s anatomy.

Eyelid retraction surgery can help significantly with dryness and exposure keratopathy. Lateral permanent tarsorrhaphy also may help and be used alone or in combination with eyelid retraction surgery.

Step 4: Cosmetic procedures. Procedures can include upper and lower blepharoplasty, fillers and botulinum toxin treatments.

“These four surgical steps are only guidelines,” says Dr. Hwang. “Some steps can be combined or skipped depending on patient needs. The goal is to offset the disfiguring effects of TED, empowering patients to feel more confident about resuming their normal activities.”

Advertisement

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Study is first to show reduction in autoimmune disease with the common diabetes and obesity drugs

It’s the first step toward reliable screening with your smartphone

Fixational eye movement is similar in left and right eyes of people with normal vision

Oral medication may have potential to preserve vision and shrink tumors prior to surgery or radiation

A new online calculator can determine probability of melanoma

Only 33% of patients have long-term improvement after treatment

Novel collaborative approach helps patient avoid orbital exenteration