Only 33% of patients have long-term improvement after treatment

When the drug teprotumumab was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2020 for the treatment of thyroid eye disease (TED), Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute’s Catherine Hwang, MD, was an enthusiastic advocate.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“Finally we had a drug that could help patients with TED, one of the most difficult diseases I treat,” says Dr. Hwang, an oculofacial plastic surgeon. “I prescribed it a lot and became one of the biggest prescribers in the Northeast U.S. But some patients started coming back with reactivated TED — more than I had seen in patients not treated with the drug. Up to that point, reactivations had been rare, so I thought it was strange.”

Patients were returning with reactivated TED up to two years after treatment with teprotumumab, a time when Dr. Hwang expected them to be long past the active phase of disease, stabilized and ready for surgical rehabilitation. Even patients who had received a second round of treatment with the drug were presenting with newly active disease.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/9b56fdd7-b23a-4d33-9eac-3c2004e6eef2/teprotumumab-to-treat-thyroid-eye-disease)

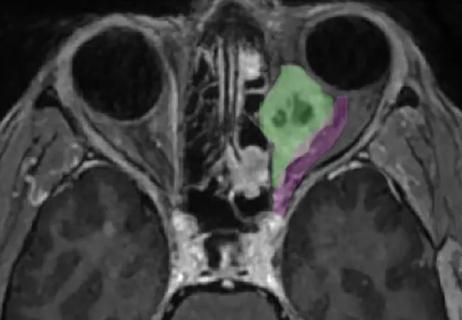

Initial presentation of patient with TED (A); one month after completing treatment with teprotumumab (B); reactivation of TED eight months after completing treatment (C).

Initially after treatment, most patients had recorded a Clinical Activity Score (CAS) of 0 or 1, indicating no symptoms of TED. Patients presenting with reactivated disease, months or years after treatment, recorded a CAS of 3 or higher.

Prior to FDA approval, phase 2 and phase 3 trials of teprotumumab published in The New England Journal of Medicine showed improvement in proptosis and motility for people with TED. However, these outcomes were reported soon after the completion of treatment, eight infusions of the drug over six months. Long-term data was not available.

“The initial studies were trying to detect any response to the drug,” says Julian Perry, MD, an oculofacial plastic surgeon at Cleveland Clinic Cole Eye Institute. “Treating TED is a challenge for patients and their physicians, so any effect from teprotumumab would be encouraging. But any effect isn’t necessarily a meaningful effect.”

Advertisement

As a result, Drs. Hwang and Perry began to research longer-term data to understand more about the durability of teprotumumab. Their study, recently published in the American Journal of Ophthalmology, revealed that only about one-third of patients have long-term improvement of TED after treatment with the drug.

“The medication originally was lauded because it was novel and seemingly quite effective,” says Dr. Hwang. “Unfortunately, the longer we go, the more failures we see. And these failures are not just a regression in effect. They are a complete loss of effect in the setting of active inflammation. That’s important because it could mean that the drug is actually prolonging the active phase of TED.”

Drs. Hwang and Perry and their research team reviewed the outcomes of 21 patients with TED who were treated with teprotumumab at the Cole Eye Institute between May 2020 and May 2021. Patients had between six and 24 months of follow-up after their last infusion of the drug.

Of these 21 patients:

Advertisement

On average, in the 17 patients who initially responded to treatment, proptosis improved by less than 2 mm (range: -3 mm to 4 mm).

“That minor improvement likely would not alleviate the need for reconstructive surgery, which is what we’re trying to prevent,” says Dr. Hwang. “So, even for the 33% of patients who had sustained success with the therapy, there may not have been an appreciable clinical response.”

The study’s secondary outcome was change in diplopia. Diplopia did improve for some patients after treatment but eventually returned to baseline.

“There was no statistically significant change in diplopia for any patient,” says Dr. Hwang. “Patients still required management with prisms or eye-muscle surgery.”

Currently, Dr. Hwang continues to offer conventional treatment to patients with TED, including those who present with reactivation of disease after being treated with teprotumumab.

“Retreatment with the drug is often not tolerated as well and can increase the risk of the hearing-loss side effect,” she says. “For now, it seems that teprotumumab prolongs active disease in some patients. As a result, I treat patients with intravenous steroids; recommend orbital radiation, if they’re a candidate; or do watchful waiting, encouraging smoking cessation and ensuring their thyroid is well controlled.”

To date, there have been no comparative studies evaluating these standard treatments against teprotumumab.

“For most patients, teprotumumab appears to be disease-modulating — temporarily lessening the disease — but not disease-modifying — changing the course of disease,” says Dr. Perry. “While that may seem discouraging, we should focus efforts on the drug’s disease-modulating abilities. It’s still an important medicine. We just need to harness it and potentially combine it with other therapies to develop a disease-modifying treatment.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Registry data highlight visual gains in patients with legal blindness

Study is first to show reduction in autoimmune disease with the common diabetes and obesity drugs

It’s the first step toward reliable screening with your smartphone

Fixational eye movement is similar in left and right eyes of people with normal vision

Oral medication may have potential to preserve vision and shrink tumors prior to surgery or radiation

A new online calculator can determine probability of melanoma

Novel collaborative approach helps patient avoid orbital exenteration

Interventions abound for active and stable phases of TED