Recognizing the distinctive clinical picture

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/c23a29a8-1479-4c3f-8b86-4110ad11838e/MeaslesKid-jpg)

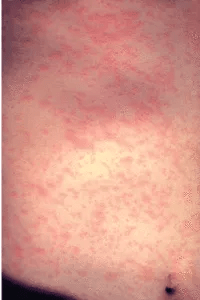

Measles

By Dheeraj Kumar, MD and Camille Sabella, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Despite widespread vaccination against measles in the United States, outbreaks continue to occur. Clinicians should be able to recognize its distinctive clinical picture so that isolation measures can be instituted promptly, susceptible contacts immunized, and public health agencies notified. Vaccination is safe for most people and should be strongly promoted for all healthy children.

Measles continues to rear its head in the United States. Because it is so contagious, even the few cases introduced by travelers quickly spread to susceptible contacts. Life-threatening and severely disabling complications can occur, although this is rare. Widespread immunization and prompt recognition and isolation of contacts are key to controlling outbreaks. This article reviews the epidemiology of measles, describes its distinctive clinical picture, and provides recommendations for infection control and prevention, including in immunosuppressed populations.

Up to 90% of susceptible people develop measles after exposure, making it one of the most contagious of infections. The virus is transmitted by airborne spread when an infected person coughs or sneezes, or by direct contact with infectious droplets. The virus can remain infectious in the air or on a surface for up to two hours.1 Worldwide, an estimated 20 million people are infected with measles each year, and 146,000 die of complications. In 1980, before widespread vaccination, 2.6 million deaths were attributable to measles annually. In the United States before the introduction of measles vaccine in 1963, measles was a significant cause of disease and death: an estimated 3 to 4 million people were infected annually, although only about 549,000 were reported. There were 48,000 hospitalizations, 1,000 cases of permanent brain damage from measles encephalitis, and 495 deaths annually.2

Advertisement

In 2000, measles was declared eliminated from the United States,3 but annual outbreaks have occurred since then as a result of cases imported from other countries and their subsequent transmission to unvaccinated people. From 2001 to 2012, a median of four outbreaks and 60 cases were reported annually to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.4 In January 2015, a multistate measles outbreak originating in Disneyland in California was recognized. As of April 17, when the outbreak was declared over, 111 measles cases from seven states had been linked to this outbreak.5 Of the evaluable cases, 44% were in unvaccinated people and 38% were in those whose vaccination status was unknown or undocumented. The median age of patients was 21, and 20% required hospitalization. This outbreak, as well as four other smaller US outbreaks the same year, underscores the transmissibility of the virus in populations containing only a small percentage of unvaccinated people.6

The incubation period for measles infection is 7 to 21 days, with most cases becoming apparent 10 to 12 days after exposure. Measles should be suspected in a patient with the following clinical features whose history indicates susceptibility and exposure (i.e., an unimmunized person with a history of exposure or travel):

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4135f2a0-3358-4724-8f3b-046a844b0a84/kumar_measles_f1_gif)

Koplik spots (arrow), indicating the onset of measles, in a patient who presented three days before the eruption of skin rash.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/9fd3934c-fda2-472f-a04a-784f17579219/kumar_measles_f2-200x300_gif)

Measles on the third day of rash.

Those at highest risk for measles complications are infants, children under age 5, adults over age 20, pregnant women, and immunosuppressed individuals.7

Advertisement

Laboratory confirmation of measles is recommended for suspected cases. Because viral isolation is technically difficult and is not readily available in most laboratories, measles-specific immunoglobulin M antibody serologic testing is most commonly used. It is almost 100% sensitive when done two to three days after the onset of the rash.15 Measles RNA testing by real-time polymerase chain reaction to detect measles virus in the blood, throat, or urine is more specific and if available may be preferred over serologic testing.16

No specific antiviral therapy for measles is available. Management involves supportive measures and monitoring for secondary bacterial complications. The World Health Organization and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend vitamin A supplementation for all children with acute measles.17 In developing countries, it has been shown to reduce rates of morbidity and death in measles-infected children.18 In the United States, children with measles have been found to have low serum levels of vitamin A, with lower levels associated with more severe disease.

Advertisement

Note: This is an abridged version of an article originally published in the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine.

Advertisement

Findings hold lessons for future pandemics

One pediatric urologist’s quest to improve the status quo

Overcoming barriers to implementing clinical trials

Interim results of RUBY study also indicate improved physical function and quality of life

Innovative hardware and AI algorithms aim to detect cardiovascular decline sooner

The benefits of this emerging surgical technology

Integrated care model reduces length of stay, improves outpatient pain management

A closer look at the impact on procedures and patient outcomes