Innovative hardware and AI algorithms aim to detect cardiovascular decline sooner

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/1b2747cf-57b6-4e78-ac9b-31f876ca2cbc/Tandon-congenital-heart-disease)

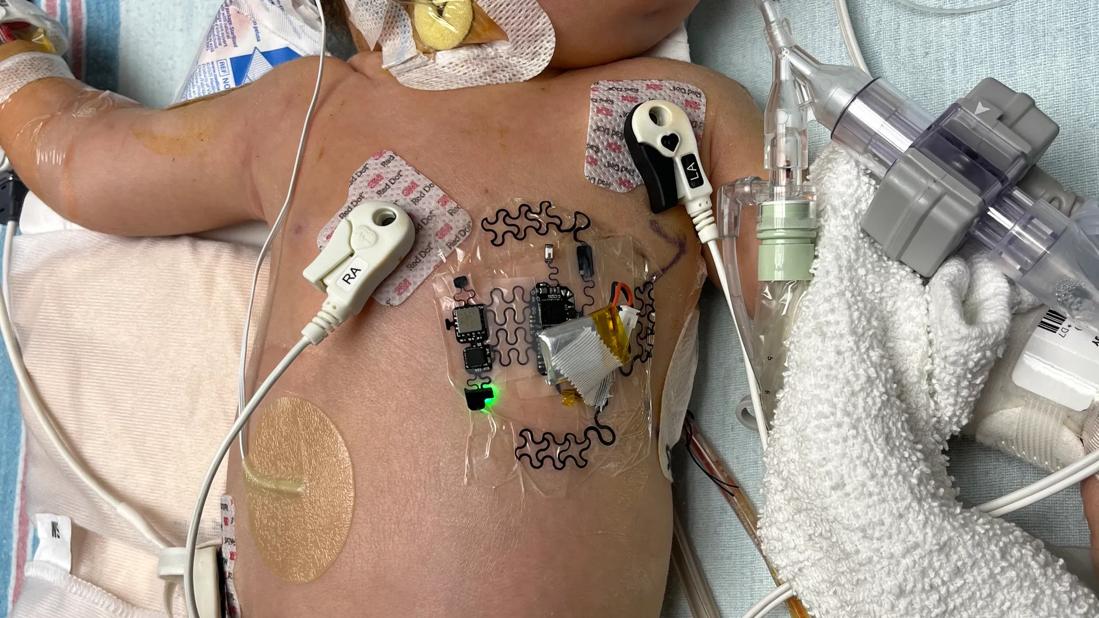

Wearable sensor on the chest of a baby

For children and adults with congenital heart disease (CHD), a new class of wearable devices could enable ICU-level monitoring in everyday settings. While technologies exist for outpatient monitoring of functional heart disease, few are available for CHD.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“The demand for CHD monitoring is increasing as more patients are living longer, healthier lives,” says Cleveland Clinic pediatric cardiologist Animesh (Aashoo) Tandon, MD. “Patients with chronic forms of congenital heart disease can progress slowly over time, and we see them in clinic only every six to 12 months. If they wear a monitor at home, we may be able to detect a decline earlier so we can address it sooner.”

The same monitoring technologies could benefit patients with CHD who are too young for surgery or between stages of operation, when risk is highest for adverse events that can lead to hospitalization or death.

Dr. Tandon and biomedical engineers at Georgia Institute of Technology, The University of Texas at Austin and The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center are taking the next steps in developing the novel monitoring device and its associated AI algorithms thanks to a recent award from the U.S. Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H).

“Financially, the ARPA-H award is similar to a National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 grant, although it’s over only two years instead of four or five years,” Dr. Tandon explains. “ARPA-H awards are designed for daring projects that are faster moving than typical NIH grants.”

Over the next two years, the research team will develop a wearable monitoring device and software to track various physiological data in children with CHD. They will work to validate these tools in patients in the ICU after heart surgery, as well as in medically stable inpatients. Future research will test the tools in patients at home.

Advertisement

Before joining Cleveland Clinic in 2021, Dr. Tandon studied multimodal wearable sensors at UT Southwestern.

“The sensors adhere to the chest and measure things about the heart that we don’t typically measure — including seismocardiography, chest vibration from the opening and closing of heart valves,” says Dr. Tandon. “I thought it was cool technology that was being used to monitor heart failure in adults and wondered if we could try it in kids and adults with CHD.”

During a University of Texas science conference, he met a UT Austin biomedical engineering team led by Nanshu Lu, PhD, that was exhibiting a seismocardiography device. When Dr. Tandon learned that they’d never tried using the technology in children, he suggested they work together to do it.

Months later, at an American Heart Association meeting on wearable biosensors, Dr. Tandon was inspired to connect with Georgia Tech’s Omer Inan, PhD, who had recently published some notable research on seismocardiography. By chance, they sat next to each other at the meeting.

Over the next eight years, the trio of research teams worked to make seismocardiography hardware more useful for children with CHD, publishing papers on using the devices to measure cardiac output of patients getting a cardiac MRI and improving design of the sensors.

“The new award is a culmination of our long-term collaboration, pulling together the best people to solve different parts of the problem,” Dr. Tandon says.

The team’s work funded by the ARPA-H award will have three facets:

Advertisement

“In the ICU, we have invasive catheters, frequent blood draws, EKG leads, pulse oximetry and other technologies to help us monitor patients,” Dr. Tandon says. “But are we monitoring the right things? Are we interpreting the data correctly? Our test device adds new readouts to the current physiological readouts. If we can track data continually, maybe we could create a risk score based on novel readouts of cardiac physiology that we don’t have right now. We first need to devise appropriate hardware that measures appropriate data.”

Monitors currently used in patients with functional heart disease aren’t necessarily useful in patients with CHD, Dr. Tandon notes. Patients with CHD have differently formed hearts that do not have the same mechanics as standard hearts.

“All of CHD is personalized medicine,” he says. “Every heart has unique mechanics. You can’t presume how blood flows through a heart with congenital disease.”

For this reason, the development of AI algorithms will be necessary to assess sensor data.

“Because there is no ‘normal’ or ‘standard’ in CHD, we need to detect when a patient deviates from what is normal for them,” explains Dr. Tandon.

The researchers hope their work will result in detecting declining cardiovascular function in ICU patients sooner, when the condition is clinically actionable.

“We’ll be monitoring patients after congenital heart surgery, whom we know could develop low cardiac output syndrome at some point,” Dr. Tandon says. “We have experienced nurses and reliable ICU monitoring that can detect outcomes of low cardiac output, such as lactic acidosis and kidney injury, but currently we’re not sophisticated enough to notice subtle changes in cardiac output before the downstream effects occur.”

Advertisement

By interrogating different parts of a patient’s physiology with a novel sensor and combining all the novel data streams, researchers hope to get a better picture of when a deviation first develops.

“When we see something happen in the ICU, we can go back and review which indicators from the wearable device might have predicted its development,” Dr. Tandon says. “Could we have treated the emerging condition an hour or two earlier?”

Patients will be prospectively enrolled in the study, but analysis of data will not be done in real-time during this stage of research. Still, commercialization of this innovation is the ultimate goal, says Dr. Tandon, who also serves as Vice Chair for Innovation and Director of Cardiovascular Innovation at Cleveland Clinic Children’s.

“Low cardiac output syndrome is the leading cause of postop mortality in CHD,” he says. “We need to do a better job for these patients. Once we figure out how to do it in the inpatient realm, we can take the same idea — using multimodal sensors to detect when a specific patient deviates from their normal — to outpatients with CHD.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

Experts advise thorough assessment of right ventricle and reinforcement of tricuspid valve

Reproducible technique uses native recipient tissue, avoiding risks of complex baffles

A reliable and reproducible alternative to conventional reimplantation and coronary unroofing

Program will support family-centered congenital heart disease care and staff educational opportunities

Case provides proof of concept, prevents need for future heart transplant

Pre and post-surgical CEEG in infants undergoing congenital heart surgery offers the potential for minimizing long-term neurodevelopmental injury

Science advisory examines challenges, ethical considerations and future directions