Overcoming barriers to implementing clinical trials

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f6faea42-5bd1-4d1a-8c32-eb3aabc2b286/kidney-disease-hero)

MRI images of pediatric kidney disease

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) is a genetic disease that affects both kidneys (polycystic kidney disease) and liver (congenital hepatic fibrosis).1 It occurs in approximately 1 in 20,000 children, the majority of whom present in the prenatal or neonatal period. A smaller number will not be diagnosed until early childhood or even in adolescence.

While ARPKD was once thought to be almost universally fatal, with modern neonatal care, the majority (>70%) of affected newborns survive the neonatal period. Unfortunately, about half of patients with ARPKD will develop kidney failure by adolescence. There are currently no disease-specific treatments available, despite encouraging studies in animal models that suggest existing or novel medications could slow the decline in kidney function.

A major barrier to translating these preclinical findings into clinical trials in ARPKD is the absence of biomarkers to identify high-risk patients, who may have normal or mildly decreased kidney function but will show more rapid decline than others with similar levels of kidney function. Similarly, biomarkers to assess the impact of a therapy during a clinical trial are also lacking. These biomarker “gaps” are of critical importance since ARPKD is rare, with relatively few patients available to participate in clinical trials.

Our collaborative team includes Dr. Chris Flask, a magnetic resonance imaging physicist at Case Western Reserve University, and me, a pediatric nephrologist and clinical researcher, at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. We have worked for over 15 years to address this important barrier to implementing ARPKD clinical trials and bring new treatments to these patients. Using novel magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, including novel MR fingerprinting (MRF), we developed and validated several MRI imaging biomarkers in rodent ARPKD models.2

Advertisement

More recently, with further refinements, we have successfully translated these findings to human ARPKD,3,4 and we performed the first-ever study of three of these quantitative MRI techniques in patients with ARPKD.5 These measures, MRF-T1 and T2 mapping (to measure cystic burden) and arterial spin labelling (ASL-MRI, to assess perfusion), do not require sedation or injectable contrast and can be performed on clinical scanners in children as young as 6 years old.

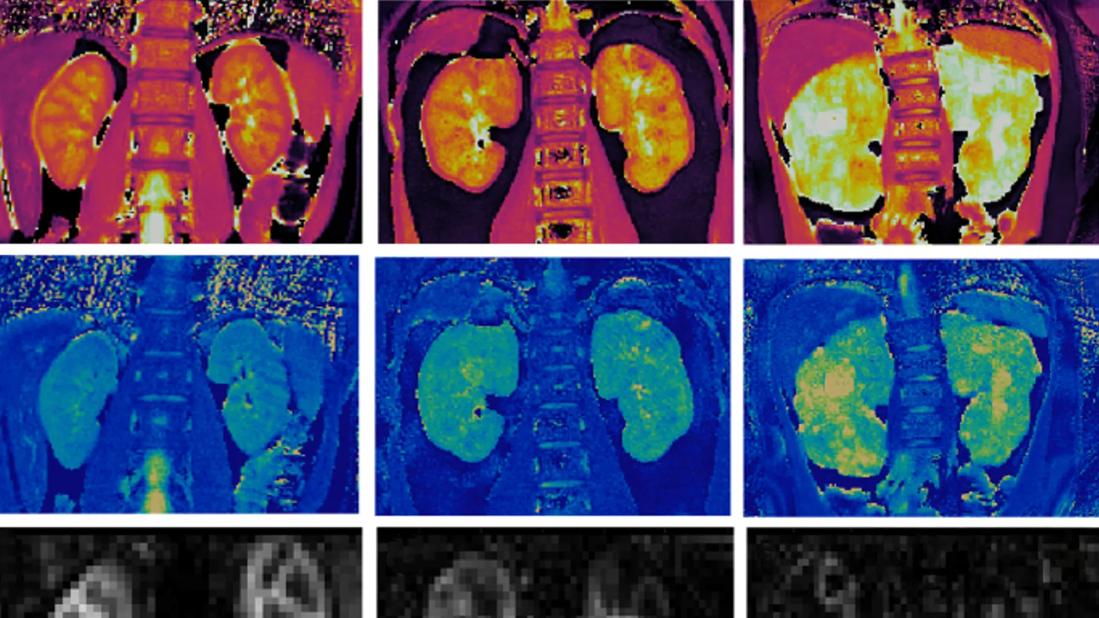

In this National Institutes of Health-funded (R01DK114425) study of 13 patients with ARPKD (ages 6 to 22) and eight healthy young adult volunteers, we found that mean kidney T1 and T2 values were significantly increased, and kidney perfusion was significantly decreased in the patients with ARPKD compared to healthy volunteers (Figure 1J-L). Importantly, mean T1 and T2 reliably distinguished ARPKD patients with early chronic kidney disease (CKD) from those with mild-moderate CKD. Of particular interest was the finding that these imaging techniques, taken as a whole, could identify differences between ARPKD subjects with relatively similar and well-preserved kidney function (Figure 1A-I).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/839049ee-8ff2-41ec-838d-4a5007cac4bb/kidney-disease-inset)

Figure 1. Multimodal imaging in patients with ARPKD and healthy volunteers. Representative kidney (a–c) T1, (d–f) T2, and (g–i) perfusion maps from a healthy volunteer (left column) and 2 pediatric patients with ARPKD (middle and right columns). (J-L) Box and Whisker plots for mean kidney (j) T1, (k) T2, and (l) perfusion from 8 healthy volunteers and 13 patients with ARPKD divided into 2 cohorts: early CKD (eGFR ≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2, n= 7) and mild to moderate CKD (eGFR 52–89 ml/min/1.73 m2, n=6). MRI assessments of cystic burden (mean T1 and T2) detected significant differences between the cohorts of patients with ARPKD with early and mild to moderate CKD (P < 0.02 and P < 0.005, respectively) as well as between the patients with ARPKD with early CKD and the healthy volunteers (P < 0.001). The ASL-based perfusion assessments showed a significant difference between the patients with ARPKD with early CKD and healthy volunteers (P= 0.02) but no significant difference between the early versus mild to moderate CKD ARPKD cohorts (P=0.20). All 3 MRI biomarkers showed significant differences between the volunteers and ARPKD subjects with mild to moderate CKD (P<0.001).

Building on these very encouraging initial findings, we recently launched a longitudinal, prospective, observational study, IMAGE-ARPKD (Imaging Assessments of ARPKD Kidney Disease Progression), available at clinicaltrials.gov (Study ID NCT07201025). This study is supported by a five-year grant from the NIH (R01DK114425) and is actively recruiting at two sites (Cleveland Clinic Children’s and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia).

Advertisement

By examining these imaging biomarkers over time in relationship to changes in measured kidney function in a larger ARPKD cohort, we hope to demonstrate that one or more of these biomarkers can identify high-risk patients and further the goal of implementing clinical trials for patients with ARPKD.

We are also proud to be a PKD Foundation-designated Pediatric Center of Excellence, one of only four in the U.S. This distinction means we offer comprehensive, specialized care for pediatric patients, including diagnostic and therapeutic services. We manage care for pediatric patients with all forms of kidney disease and collaborate closely with other specialists in the pediatric nephrology/urology clinic and Cleveland Clinic Transplant Center.

References

Advertisement

About the author. Dr. Katherine Dell is a pediatric nephrologist, clinical researcher, Professor of Pediatrics at Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University and an internationally recognized expert in pediatric polycystic kidney diseases. She directs the PKD Foundation-designated Pediatric PKD Center of Excellence, one of only four in the US.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Researchers pair quantitative imaging with AI to improve surgical outcomes in nonlesional epilepsy

Advances in imaging technology could offer new insights for combatting age-related muscle loss

Mounting support for the newly described microstructure from a 7T MRI and electroclinicopathologic study

Findings hold lessons for future pandemics

One pediatric urologist’s quest to improve the status quo

Interim results of RUBY study also indicate improved physical function and quality of life

Innovative hardware and AI algorithms aim to detect cardiovascular decline sooner

The benefits of this emerging surgical technology