NAID is a systemic disease involving multiple organs

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/29fe21f2-75af-4502-aafa-de641eb3ef4b/Macrophage-Cells_Yao_690x380pxl_jpg)

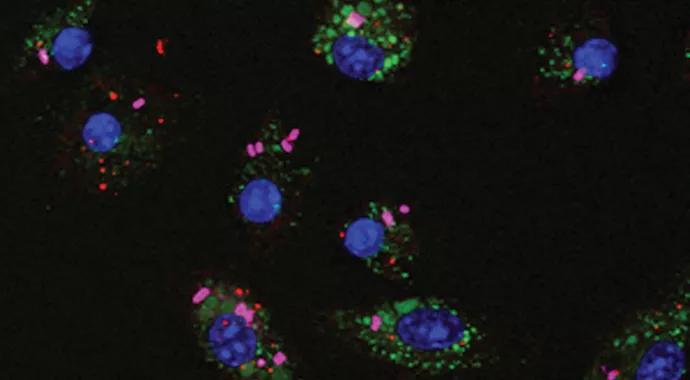

Macrophage-Cells_Yao_690x380pxl

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Autoinflammatory diseases were initially defined as seemingly unprovoked episodes of inflammation, without high-titer autoantibodies or antigen-specific T cells.1 It has been recently proposed that these diseases are clinical disorders marked by abnormally increased inflammation, mediated predominantly by the cells and molecules of the innate immune system, with a significant host predisposition.2 They represent a wide disease spectrum, ranging from Mendelian disorders to genetically complex diseases.

My Cleveland Clinic colleagues and I recently reported a new autoinflammatory disease associated with nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2) gene mutations.3 This new entity is designated NOD2-associated autoinflammatory disease (NAID).

We prospectively studied a cohort of 22 patients seen in our clinic between January 2009 and February 2012.4 We have found that NAID is a systemic disease involving multiple organs. All patients with NAID to date have been white, and while both sexes are affected, there is a slight female predominance. The mean age at diagnosis is 40.1 years (range, 17-72), and mean disease duration is 4.7 years (range, 1-13). Most patients do not have a family history of periodic fever syndromes.

Common constitutional manifestations include flu-like symptoms, weight loss and fatigue. NAID is primarily characterized by episodic self-limiting fever (observed in 59 percent of cases), dermatitis (86 percent) and inflammatory polyarthritis/polyarthralgia (91 percent). Patients with dermatitis usually present with intermittent erythematous plaques, patches and macules (see figure), and dermatopathology reveals mostly spongiotic dermatitis and, occasionally, granulomatous changes. About one-third of patients with NAID have distal lower extremity swelling.5 Patients with NAID also can experience gastrointestinal symptoms (observed in 59 percent), sicca-like symptoms (41 percent) and recurrent chest pain (22 percent).

Advertisement

Forty percent of patients have elevated acute-phase reactants. All patients test negative for autoantibodies for systemic autoimmune diseases. All patients carry the NOD2 gene mutations, with the intervening sequence variant IVS8+158 in 95 percent, the R702W variant in 36 percent and R703C in rare cases.6 These NOD2 mutations are located in between the leucine-rich repeat region and the nucleotide binding domain.7 NAID is distinct from pediatric Blau syndrome and other periodic fever syndromes.

While there have been extensive studies about the NOD2 mutations and diseases,7 the pathogenetic role of the NOD2 gene mutations in NAID is unclear. We believe that the NOD2 gene mutations are presently considered to serve as a diagnosticmolecular tool. We assume that gene dosage effects of NOD2 may play a role in the disease; NAID may represent a polygenicauto inflammatory disease, given the rarity of family history and the evidence suggesting that NAID does not appear to be rare. Afurther study of NAID pathogenesis is under way.

Pharmacologic therapy for patients with NAID remains empiric, depending on clinical manifestations. Generally, patients with fever or skin disease respond well to small doses of prednisone (< 20 mg daily). Some patients with inflammatory arthritis respond to sulfasalazine treatment. Hydroxychloroquine and methotrexate have not proven effective for treating this disease. The therapeutic role of biologics, such as TNF-α inhibitors and IL-1 antagonists, needs to be determined. Future studies will also focus on the innate immune response and cytokine profile in patients with NAID.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/96e55013-9150-4fee-87d2-da57f394db3f/Dermatitis_Yao_590pxl-width_jpg)

Figure. Dermatitis in patients with autoinflammatory disease and NOD2 gene mutations. (A and B) Erythematous plaques on the face and forehead (A) and the lower leg (B). (C) Patchy erythema on the upper chest. (D) Erythematous macules on the calf. (E) Pink macules on the arm and back.

1. Yao Q, Furst DE. Autoinflammatory diseases: an update of clinical and genetic aspects. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47:946-951.

2. Kastner DL, Aksentijevich I, Goldbach-Mansky R. Autoinflammatory disease reloaded: a clinical perspective. Cell. 2010;140:784-790.

3. Yao Q, Zhou L, Cusumano P, et al. A new category of autoinflammatory disease associated with NOD2 gene mutations. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(5):R148.

4. Yao Q, Su LC, Tomecki KJ, Zhou L, Jayakar B, Shen B. Dermatitis as a characteristic phenotype of a new autoinflammatory disease associated with NOD2 mutations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(4):624-631.

5. Yao Q, Schils J. Distal lower extremity swelling as a prominent phenotype of NOD2-associated autoinflammatory disease [Epub ahead of print April 12, 2013]. Rheumatology. 2013;Nov;52(11):2095-7.

6. Yao Q, Piliang M, Nicolacakis K, Arrossi A. Granulomatous pneumonitis associated with adult-onset Blau-like syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:465-466.

7. Yao Q. Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2: structure, function, and diseases [Epub ahead of print Jan. 24, 2013]. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Aug;43(1):125-30.

Dr. Yao is a staff physician in the Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases. He can be reached at 216.444.5625 or yaoq@ccf.org.

Advertisement

Reprinted from reference 4 (Yao et al), ©2012, with permission from the American Academy of Dermatology.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Researching the biological basis for why treatment is or is not effective

Scribing system helps create more face-to-face interactions

A conversation with Leonard Calabrese, DO

The case for continued vigilance, counseling and antivirals

High fevers, diffuse rashes pointed to an unexpected diagnosis

No-cost learning and CME credit are part of this webcast series

Summit broadens understanding of new therapies and disease management

Program empowers users with PsA to take charge of their mental well being