New research from Cleveland Clinic helps explain why these tumors are so refractory to treatment, and suggests new therapeutic avenues

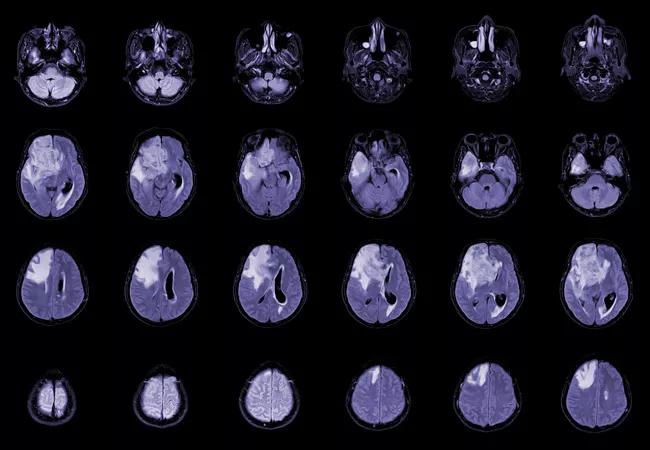

Cleveland Clinic Cancer Center researchers are honing in on how the currently-incurable primary brain tumor glioblastoma notoriously evades treatment, with their findings pointing to potential approaches that could stop the cancer in its tracks. The data was presented at the 2023 ASTRO annual meeting.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

About 15,000 people per year in the United States are diagnosed with glioblastoma.

In a new series of studies, Cleveland Clinic radiation oncologist Jennifer S. Yu, MD, PhD, and her team identified interactions between two developmental pathways involved in tumor progression. Blocking just one has been tried but doesn’t work, in part because the other pathway can promote the same downstream processes. Targeting both could represent a way to stymie tumor reactivation.

“The cancer is refractory to essentially everything that we try to treat it with,” Dr. Yu explains. “The cancer stem cell is highly resistant to radiation and chemotherapy, and that’s one reason these cancers progress. Even though these cells are a very small percentage of the total tumor cell population, because they exist and survive the treatment, they can then expand and give rise to a whole new tumor.”

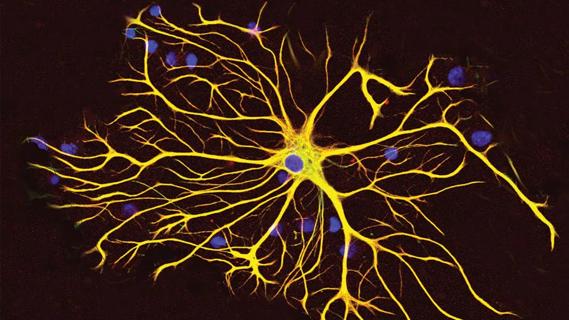

Her lab examines ways to identify therapeutic vulnerabilities of these cancer stem cells. The stem cell pathways, or developmental programs, are abnormally active in mature cells. “These cancer stem cells have somehow found a way to reactivate developmental programs that should be dormant,” she notes.

One of these pathways, called Wnt, has long been known to be deregulated in many cancers. In the Wnt pathway, Wnt ligands bind to their receptors to stabilize the transcription factor protein β-catenin, ultimately leading to β-catenin translocation to the nucleus. Nuclear β-catenin then binds to TCF1 to drive transcription of Wnt target genes that then drive cancer progression.

Advertisement

But agents that target the Wnt pathway have failed in patients with glioblastoma, while also causing unacceptable gastrointestinal toxicity.

About ten years ago, Yu’s group identified a second, parallel neurodevelopmental pathway called Semaphorin 3C (Sema3C). It is reactivated by glioma stem cell populations and selectively used by them but not by other tumor cell populations.

“Even if you have an inhibitor acting on the Wnt pathway, because of this activation of the Semaphorin pathway, the tumor cell doesn’t actually care whether the Wnt protein binds its receptor. You can block that interaction, but you have an alternative way of driving the main effector of cancer stem cell survival and self-renewal, which is further downstream,” Yu explains.

Now, for the first time, Yu’s group has shown that the Sema3C pathway also controls the activity of β-catenin. Sema3C does this by binding to its receptor complex, which in turn activates a protein called Rac1. Active Rac1 then facilitates β-catenin’s movement into the nucleus.

“So, β-catenin is the key protein that is regulated by both pathways,” Dr. Yu says. “People never knew before that a Semaphorin pathway could regulate β-catenin. This is important because it explains in part why, aside from the toxicity issues, patients don’t respond well to Wnt inhibitors. But now if you were to block both the Sema3C and Wnt pathways, then you could inhibit the function of β-catenin much more effectively. And, you might be able to reduce the dose of the Wnt pathway inhibitor because you won’t need quite as much of it.”

Advertisement

In the new series of experiments, Yu and colleagues confirmed that Wnt inhibitors had no effect on tumors in murine models, and that when used together, Sema3C and TCF-1 reduced tumor size and extended survival. The researchers demonstrated that knocking out Sema3C reduced expression of several genes in the Wnt pathway. Conversely, over-expressing Sema3C in glioma stem cells resulted in higher levels of expression of Wnt target genes.

“We’re knocking out each component of the pathway and showing the same results. We’re trying to connect the dots,” she says.

They also performed a series of “rescue” experiments. For example, when they blocked Sema3C but replaced an active form of Rac1 downstream, they were able to reverse the effects of losing Sema3C.

Currently there is no effective way to target the Sema3C pathway, but Yu’s lab is working on it. “Looking downstream at the Sema3C pathway, there are potential proteins that can be targeted with drugs that are already out there. So, there are promising therapeutic strategies to target this pathway,” she says.

The lab has just received a $2 million R01 award from the National Institutes of Health for this work. “Once we get the preclinical pieces together, we may be able to start clinical trials in three or four years. Ultimately, I hope this will offer new therapies that can improve patients’ lives. It is very exciting.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

Phase 2 trials investigate sitagliptin and methimazole as adjuvant therapies

Advances in genomics, spinal fluid analysis, wearable-based patient monitoring and more

Researchers use AI tools to compare clinical events with continuous patient monitoring

Combining dual inhibition with anti-PD1 therapy yielded >60% rate of complete tumor regression

Cleveland Clinic researchers pursue answers on basic science and clinical fronts

Presurgical planning and careful consideration of pathology are key to achieving benefits

Study demonstrates its role in tumor lethality, raises prospect of therapeutic targets

Focused ultrasound is paired with ALA to utilize sonodynamic therapy to target cancer cells