Intracranial injection of supercharged immune cells proceeds to phase 2 testing

Immunotherapy has improved the outcomes for many types of cancer, but so far it has not shown benefits in treating glioblastoma. Now a new study is taking a fresh look at its potential, with a novel approach that involves injecting supercharged immune cells directly into the tumor cavity in the brain.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

The phase 1 clinical trial found that the treatment, called drug-resistant immunotherapy, was safe and feasible in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma, with no significant added side effects. A phase 2 clinical trial is scheduled to launch soon at Cleveland Clinic and other institutions.

“It is a unique approach, and we are excited to offer it to more patients in the phase 2 trial,” says the study’s first author, Mina Lobbous, MD, MSPH, a neuro-oncologist in Cleveland Clinic’s Rose Ella Burkhardt Brain Tumor and Neuro-Oncology Center. Results of the trial were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting earlier this year. The research was started at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and was co-led by Dr. Lobbous.

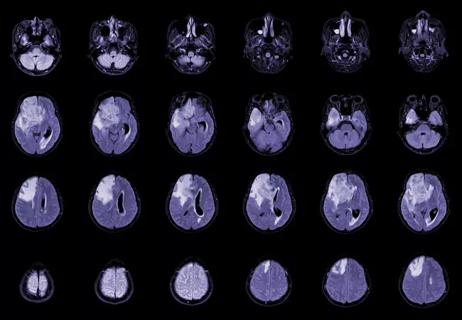

Glioblastoma, the most common malignant brain tumor in U.S. adults, is not curable. Standard of care includes surgical resection of the tumor, followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy. However, even with this multimodality approach, tumors eventually recur and lead to death.

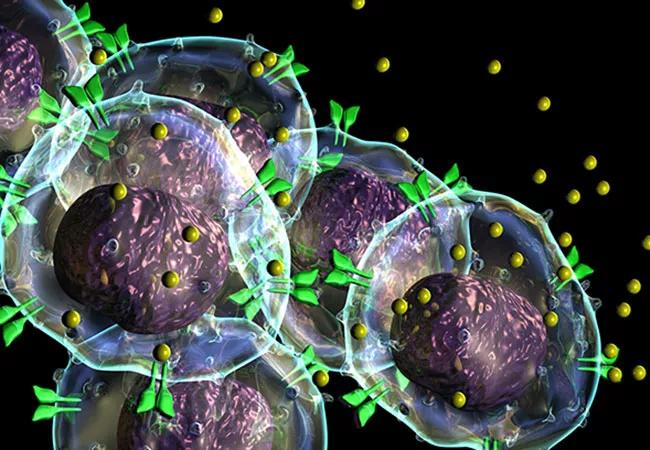

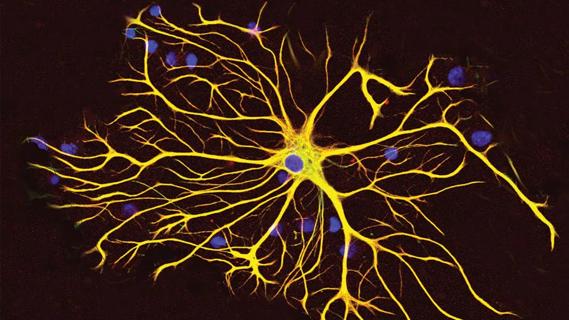

For the new treatment, a Rickman catheter is implanted in the tumor cavity during the surgical resection. After the patient has recovered from the procedure, physicians collect the patient’s own immune cells and genetically modify them — specifically the gamma delta T cells — to be stronger and resistant to chemotherapy (i.e., drug-resistant immunotherapy). Then, while the patient is undergoing standard-of-care radiation therapy and chemotherapy (temozolomide), the drug-resistant immune cells are injected through the catheter into the tumor cavity at each 28-day maintenance cycle of temozolomide.

Advertisement

“While the tumor cells are already stressed from the chemotherapy, these modified T cells go in and attack,” Dr. Lobbous explains.

A similar approach using drug-resistant immunotherapy is being tested in leukemia patients, using donor immune cells.

In the phase 1 trial, which is still ongoing at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, eight patients were dosed. In these patients, the modified immune cells showed manageable toxicity, with no dose-limiting toxicities and no worsening of side effects with repeated dosing.

Researchers saw evidence that the modified T cells were still present in the resected tumor tissue even 148 days after a single infusion. Patients who received the treatment achieved longer-than-projected progression-free survival (PFS) based on their age and status, with all patients exceeding the seven-month median PFS associated with the standard of care.

“This shows that it is safe and feasible to deliver,” Dr. Lobbous notes. “In fact, most of the side effects we have seen were related to the chemotherapy itself.”

The phase 2 clinical trial will expand investigation of this therapy to more patients across multiple sites, including Cleveland Clinic. Future studies will also look at the effectiveness of this treatment using donor immune cells.

“We’re hopeful that this approach will ultimately provide a survival benefit to our patients and also help us understand the unique features of these tumors, including why glioblastoma has been resistant to immunotherapy,” Dr. Lobbous concludes.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Phase 2 trials investigate sitagliptin and methimazole as adjuvant therapies

Advances in genomics, spinal fluid analysis, wearable-based patient monitoring and more

Researchers use AI tools to compare clinical events with continuous patient monitoring

Combining dual inhibition with anti-PD1 therapy yielded >60% rate of complete tumor regression

Cleveland Clinic researchers pursue answers on basic science and clinical fronts

New research from Cleveland Clinic helps explain why these tumors are so refractory to treatment, and suggests new therapeutic avenues

Presurgical planning and careful consideration of pathology are key to achieving benefits

Study demonstrates its role in tumor lethality, raises prospect of therapeutic targets