Rare but often treatable with early recognition

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f687c697-b1ce-4e04-ae87-b625b3cc5b26/17-NEU-729-Friedman_jpg)

17-NEU-729-Friedman

By Neil Friedman, MBChB, and Andrew Zeft, MD, MPH

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

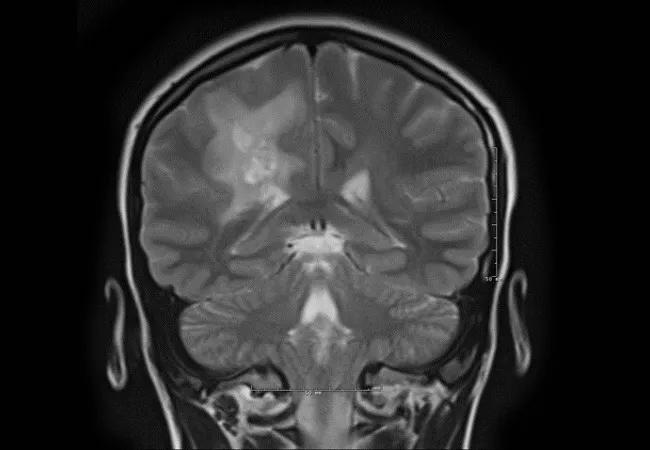

A previously healthy 14-year-old girl was seen for a second opinion at Cleveland Clinic after initially presenting for medical attention after findings of a mild left hemiplegia on clinical examination following evaluation of a sports-related knee injury. She also had problems with headache at this time. Brain MRI showed abnormal T2/FLAIR signal intensities in the deep white matter of the bilateral cerebral hemispheres, most prominent in the right parietal lobe, and demonstrated rim enhancement and surrounding edema (Figure).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3866398d-7924-41a8-86af-93930049567c/17-NEU-729-Friedman-Inset_jpg)

Figure. Multiple T2 signal lesions in the deep white matter of the right parietal lobe with surrounding edema (top three images) and rim enhancement (bottom two images).

Workup for demyelinating disease and infection was negative. Systemic inflammatory markers were similarly negative. She therefore underwent a stereotactic brain biopsy of a lesion in the right parietal lobe, which showed extensive necrotic tissue, partially thrombosed vessels and crowded inflammatory cells. Vessels were surrounded by inflammatory cells, which also involved the vessel walls. There was no evidence of CNS lymphoma. A diagnosis of small vessel CNS vasculitis was made, and she was started on immunosuppressive therapy. With therapy, she has shown a significant improvement in her left hemiplegia, with only mild functional impairment of left hand dexterity remaining.

Inflammation is increasingly recognized as a potential pathophysiological mechanism in a number of pediatric cerebral arteriopathies. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system (PACNS) is a rare, progressive, immune-mediated inflammatory process directed toward blood vessels of the CNS in the absence of systemic involvement. Inflammatory vasculitis may, however, also be part of a collagen vascular and systemic vasculitis disease or an infectious/post-infectious process.

Advertisement

Childhood PACNS (cPACNS) accounts for 2 to 6 percent of pediatric cerebral arteriopathies. Causes or provoking factors of the disorder are unknown, and the vasculitis might represent the final common pathological pathway for a number of inciting events.

Two distinct subtypes of cPACNS have been identified based on vessel size, angiographic features and pathological findings. Large/medium cerebral vessel vasculitis is usually angiographically positive (beading, stenosis or occlusion), while small vessel disease is typically negative. Each has a unique clinical presentation and radiographic features.

The large/medium vessel vasculitis typically presents with a sudden or acute neurologic event such as hemiplegia and/or symptomatic seizure corresponding to an affected vascular territory. cPACNS cases are further divided, in some classification systems, into progressive versus nonprogressive subtypes. The nonprogressive form appears synonymous with focal arteriopathy of childhood, an idiopathic, nonprogressive focal or segmental, unilateral stenosis of the distal (supraclinoid) internal carotid artery or proximal middle or anterior cerebral artery resulting in a lenticulostriate infarction. It appears to be a monophasic event, although angiographic data have shown that the stenosis may worsen over three to six months, with persistent focal narrowing of the vessel in a significant number of patients. While inflammation has been proposed as a purported mechanism, etiology remains uncertain. The progressive form needs to be differentiated from other cerebral vasculopathies such as moyamoya disease or fibromuscular dysplasia.

Advertisement

Small vessel cPACNS, on the other hand, is typically a more subacute presentation with multifocal white matter abnormalities on brain MRI, multifocal neurologic deficits, headaches, and neurobehavioral or cognitive decline. Seizures and tumor-like presentations may also occur. Full-thickness brain biopsy (including dura) is generally required for diagnosis because angiography is frequently negative. Biopsies reveal segmental, nongranulomatous, intramural infiltration predominantly of T lymphocytes in the small arteries, arterioles, capillaries or venules. Perivascular inflammation may also be seen. Occasional macrophages, polymorphonuclear cells and eosinophils may be present.

Although small vessel cPACNS is rare, it is often a treatable diagnosis. Early recognition and appropriate therapy are important for reduction of morbidity and mortality. The disorder should be considered in the differential diagnosis of subacute neurologic decline in children with focal or more diffuse neurologic features and white matter abnormalities on brain MRI. Differentiation from an autoimmune encephalitis can be difficult at times.

Therapy primarily involves immunosuppressant drugs, with steroids and pulsed cyclophosphamide used during the initial acute treatment phase, followed by long-term maintenance immunosuppression therapy with mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine. There is no consensus on concomitant use of anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy during the acute phase to prevent in situ thrombosis from vessel inflammation.

Advertisement

Dr. Friedman (friedmn@ccf.org) is Director of the Center for Pediatric Neurosciences in Cleveland Clinic Neurological Institute and Cleveland Clinic Children’s.

Dr. Zeft is a pediatric rheumatologist with Cleveland Clinic Children’s who specializes in autoimmune disorders.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Guidance from the largest cohort of SEEG-confirmed insular epilepsy patients reported to date

Ethical guidance provides guardrails so medical advances benefit patients

OCEANIC-STROKE results represent long-sought advance in secondary stroke prevention

Two studies from Cleveland Clinic may help advance the technology toward broader clinical use

Distinct MRI signature includes lesions beyond the corpus callosum, features predictive of vision and hearing loss

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges