Case study explores factors informing a tough therapy choice

By Ahsan NV Moosa, MD, and Andrew Zeft, MD, MPH

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Patient “AB” was 13 years old when he was evaluated for refractory epilepsy at Cleveland Clinic Children’s. He had experienced multiple seizure types from age 11 years, including left arm somatosensory aura, left arm/leg motor seizures and complex partial seizures with automatisms.

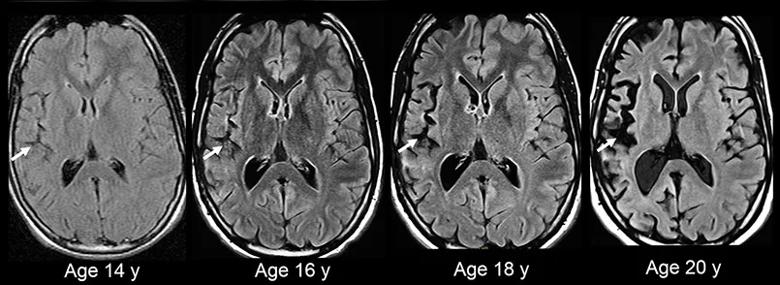

Despite taking multiple antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), he had two to three seizures per week. Serial brain MRIs revealed subtle right hemispheric atrophy that ultimately showed mild but definite progression over time (Figure 1), consistent with Rasmussen encephalitis. Biopsy from the right temporoparietal region at age 14 showed features supporting Rasmussen encephalitis.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/3c3c155d-3c06-498b-a1a6-4050a71b47d5/18-NEU-4773-Rasmussen-Encephalitis-inset1_jpg)

Figure 1. Serial brain MRIs from patient AB showing progressive right hemispheric cortical atrophy that’s most evident in the insula and perisylvian regions (white arrows).

At age 14, monthly intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) was started. Over the next four years, AB remained stable, experiencing sporadic weekly seizures but no hemiplegia. He attended college, where he was able to play basketball.

At age 19, he required hospitalization in an outside center for complex partial status epilepticus. Intravenous anesthetics were effective only temporarily, and seizures re-emerged on attempts to wean these agents. At the time he was admitted to Cleveland Clinic Children’s PICU, he had 12-15 seizures per hour despite the use of five AEDs. He had moderate left arm weakness.

Hemispherectomy was discussed but declined by the family due to the risk of irreversible left hemiplegia. Aggressive immunotherapy was started with pulse IV methylprednisolone, IVIG and tacrolimus. In the ensuing week, his seizures decreased in frequency and completely stopped by day 8. He was discharged home and was able to return to college a month later. His left arm weakness completely resolved, suggesting that the weakness had been postictal. He had sporadic seizures (a few per month) thereafter.

Advertisement

About 1.5 years later, despite ongoing immunotherapy, his condition escalated to multiple daily seizures. Because of the poor quality of life, AB and his family elected to proceed with right disconnective hemispherectomy. He developed left hemiplegia and left homonymous hemianopia following surgery. At two-year follow-up after surgery, he remained seizure-free on only one AED.

Rasmussen encephalitis is a progressive inflammatory unihemispheric disease manifesting with refractory epilepsy and progressive loss of hemispheric function, often leading to hemiplegia one to two years after disease onset. In such patients, hemispherectomy offers the best chance for seizure freedom and improved quality of life. In some children, the disease may be limited, with no hemiplegia despite a disease duration of three years or more. In such cases, immunosuppressive therapy is sometimes helpful.

The condition typically affects children between 5 and 7 years of age. Children with Rasmussen encephalitis often present with motor seizures that respond poorly to AEDs, and many develop epilepsia partialis continua. In the classic phenotype, the disease affects the perirolandic cortex and progresses fairly rapidly over one to two years, leading to hemiplegia. In atypical cases, the disease may progress slowly and be restricted to small regions outside the perirolandic cortex, so the typical motor seizures and hemiplegia may not be the dominant clinical features. Clinical follow-up and serial brain MRIs to document progressive cortical atrophy — and, in some cases, brain biopsy — may be needed to make a diagnosis. The case of AB illustrates some of these atypical features and highlights the treatment challenges.

Advertisement

In patients who already have hemiplegia and ongoing seizures, the decision to proceed with hemispherectomy is fairly straightforward. In a Cleveland Clinic study of longitudinal outcomes among 170 children after hemispherectomy, 71 percent of 21 children with Rasmussen encephalitis were seizure-free on long-term follow-up. The decision for hemispherectomy becomes challenging if the diseased hemisphere harbors language functions (usually the left hemisphere in right-handed subjects). If children develop the disease before 6 to 8 years of age, language function has a higher chance of shifting to the other hemisphere. The potential for such plasticity declines rapidly thereafter.

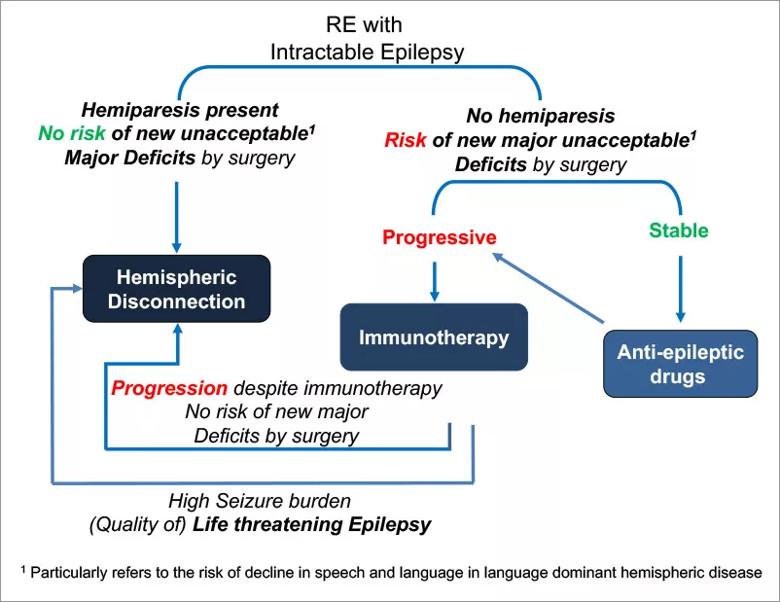

In patients without hemiplegia, most clinicians consider some form of immunotherapy (Figure 2). In our patient, the progression of Rasmussen encephalitis was very slow and he had no hemiplegia despite nearly 10 years of disease. It is unclear whether immunotherapy was beneficial in the long term in his case. However, intensified immunotherapy around the time of refractory status epilepticus appeared to have significant benefit in stopping the cycle of status epilepticus, albeit temporarily. When status epilepticus recurred despite continued immunotherapy, the patient and family elected to proceed with hemispherectomy even while understanding the risks of postoperative deficits, which they were willing to accept in exchange for seizure freedom. Families are forced to choose between decreased quality of life due to ongoing frequent seizures and decreased quality of life due to hemiplegia and hemianopia but without seizures. Such decisions are highly individualized and best made by the patients and their families, guided by experienced clinicians. AB and his family were content with their decision to choose hemispherectomy.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/9a8e2646-09cb-43a5-bbc9-cee9f30bd168/18-NEU-4773-Rasmussen-Encephalitis-inset2_jpg)

Figure 2. Schematic of treatment options for Rasmussen encephalitis.

Immunotherapy has long been tried in Rasmussen encephalitis because of the presence of inflammatory infiltrate on brain pathology. An ideal goal of immunotherapy is zero seizures with no progression of disease. However, in clinical trials of immunotherapy for Rasmussen encephalitis, results have been mixed: The improvement in seizure burden is minimal, but in many patients immunotherapy is shown to slow disease progression. Steroids are often used during acute crisis situations, and IVIG and tacrolimus are frequently used as long-term therapy. Anecdotal reports of temporary benefits have been described with other immunomodulatory therapies, such as plasma exchange, rituximab, natalizumab, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine and adalimumab.

Because the goal of zero seizures with no progression of disease by immunotherapy remains elusive, Cleveland Clinic Children’s epileptologists always collaborate with our pediatric rheumatology colleagues to explore new immunosuppressive treatment options in these cases to optimize chances for the best results.

Cho S, Zeft A, Knight EP, et al. Refractory status epilepticus secondary to atypical Rasmussen encephalitis successfully managed with aggressive immunotherapy. Neurol Clin Pract. 2017;7:e5-e8.

Moosa AN, Gupta A, Jehi L, et al. Longitudinal seizure outcome and prognostic predictors after hemispherectomy in 170 children. Neurology. 2013;80:253-260.

Bien CG, Tiemeier H, Sassen R, et al. Rasmussen encephalitis: incidence and course under randomized therapy with tacrolimus or intravenous immunoglobulins. Epilepsia. 2013;54:543-550.

Advertisement

Lagarde S, Villeneuve N, Trebuchon A, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy (adalimumab) in Rasmussen’s encephalitis: an open pilot study. Epilepsia. 2016;57:956-966.

Dr. Moosa (aka Ahsan Moosa Naduvil Valappil; naduvia@ccf.org) is a pediatric epilepsy staff physician in Cleveland Clinic’s Epilepsy Center.

Dr. Zeft (zefta@ccf.org) is Director of Cleveland Clinic Children’s Center for Pediatric Rheumatology and Immunology.

Advertisement

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges

Phase 2 trials investigate sitagliptin and methimazole as adjuvant therapies

Aim is for use with clinician oversight to make screening safer and more efficient

Rapid innovation is shaping the deep brain stimulation landscape

Study shows short-term behavioral training can yield objective and subjective gains

How we’re efficiently educating patients and care partners about treatment goals, logistics, risks and benefits