CT navigation, neuromonitoring and blood management help minimize considerable risks

By Jason Savage, MD, and R. Douglas Orr, MD

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

A 72-year-old woman presented to Cleveland Clinic reporting severe back pain and radiating leg pain (right greater than left) with standing and walking. Her symptoms had been present for approximately 5 years and had steadily worsened over the past 6 to 12 months. She also reported worsening posture and an inability to stand upright for more than 10 to 15 minutes at a time.

She had exhausted nonoperative treatment options, including multiple rounds of physical therapy, several targeted epidural steroid injections and appropriate nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications. She was seen by several surgeons outside of Cleveland Clinic who told her “nothing could be done” to help with the pain, as surgery was too risky to consider in her case. Nevertheless, she was quite debilitated by her symptoms and remained interested in moving forward with surgical intervention.

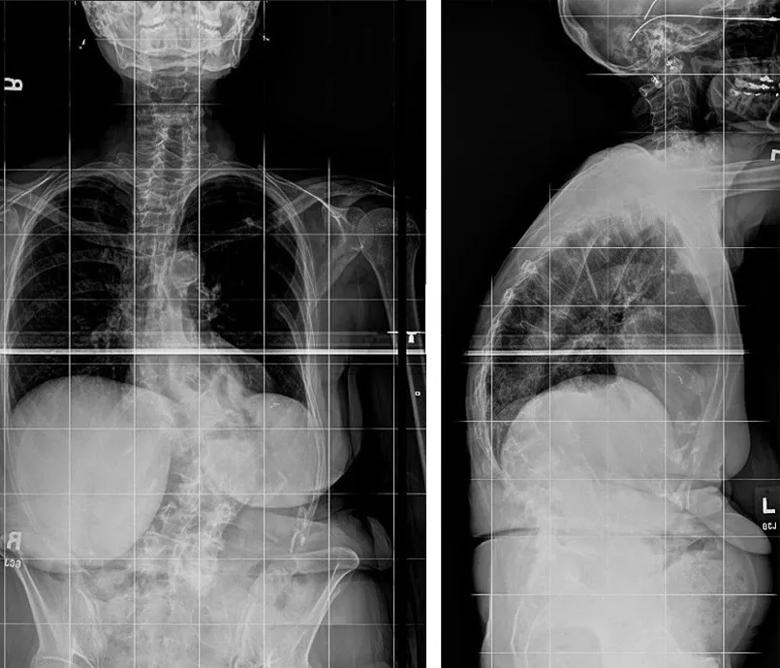

X-rays as well as MRI, CT and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scans were taken as part of the diagnostic workup. Scoliosis X-rays revealed a 55-degree convex right adult scoliosis with sagittal plane imbalance and high pelvic tilt, as well as multilevel lateral recess and foraminal stenosis (Figures 1 and 2). CT showed advanced degenerative changes with “vacuum disks” throughout the lumbar curve.

In view of the patient’s worsening symptoms and radiographic findings, she elected to proceed with surgery. An extensive multidisciplinary preoperative evaluation was done to ensure that she was optimized for the procedure. At Cleveland Clinic, this typically involves evaluation by endocrinology (bone health evaluation and management of diabetes if present), the perioperative medicine team (blood pressure management, risk stratification, smoking cessation, weight loss program, etc.), anesthesiology and physical therapy (“prehabilitation”). The surgical team oversees the entire perioperative process but relies heavily on these other specialists to minimize complications and optimize outcomes.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/374bb716-5c8a-49b0-99f1-915b54c07ca0/18-NEU-4009-spinal-fusion-scoliosis-inset1_jpg)

Figures 1 and 2. Preoperative X-rays showing convex right adult scoliosis with sagittal plane imbalance and high pelvic tilt along with multilevel lateral recess and foraminal stenosis.

The goals of surgery were to decompress the neural elements, correct the scoliosis and restore coronal and sagittal plane alignment (age-appropriate alignment objectives were used).

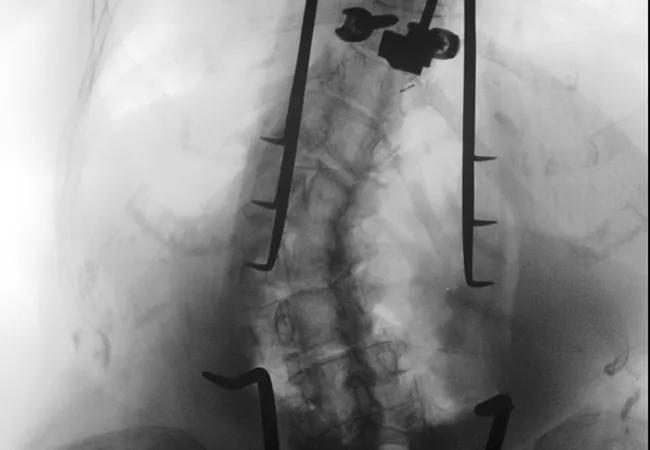

We performed a T4-sacrum posterior spinal fusion with pedicle screw instrumentation, iliac fixation and multilevel posterior column osteotomies (Schwab grade 2). Intraoperative CT navigation was used to place the pedicle screw instrumentation (Figure 3). Electrophysiological neuromonitoring with somatosensory evoked potentials and transcranial motor evoked potentials was used to ensure safety of the neural elements during placement of the screws and correction of the spinal deformity.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/763e89ec-40e5-4538-8299-b51833cba29b/18-NEU-4009-spinal-fusion-scoliosis-650x450_jpg)

Figure 3. Representative image from the intraoperative CT guidance used in placement of the pedicle screw instrumentation.

The osteotomies were performed throughout the apex of the curve to mobilize the spine. Compression, distraction and cantilever forces were used to correct the curvature and improve the overall alignment, and 6.0-mm titanium rods were used to hold the improved new posture. A third rod was used to provide more stability across the area of curve correction and across the lumbosacral junction. Local bone graft, allograft and bone morphogenetic protein were used for the fusion.

The operation was completed in approximately 6 hours (staff surgeon with spine surgery fellow) with an estimated blood loss of 800 mL. Tranexamic acid (TXA) and other blood management strategies were used to minimize blood loss and optimize fluid resuscitation during the procedure.

Advertisement

The patient was extubated in the operating room, went to the recovery room and was taken to the regular nursing floor for postoperative care. She mobilized with physical therapy on postoperative day 1 and was discharged home on day 5.

Her postoperative X-rays revealed good correction of her deformity and restoration of her overall coronal and sagittal plane alignment (Figures 4 and 5). Her preoperative leg pain has completely resolved. Her back pain has significantly improved, and her functional outcome scores (EuroQol 5D [EQ-5D], Oswestry Disability Index, Short-Form Health Status Survey [SF-36]) continue to improve relative to preoperative levels.

It is now approximately 1 year since her operation, and she can walk up to a mile and play with her grandchildren, which she could not do before the surgery. She is now looking forward to an upcoming international trip.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/2cc26f48-d5e0-44b6-bb8c-61749a8d7b04/18-NEU-4009-spinal-fusion-scoliosis-inset2_jpg)

Figures 4 and 5. Postoperative X-rays showing good correction of the deformity with restoration of overall coronal and sagittal plane alignment.

Patients with adult spinal deformity often have significant pain and disability, which is typically related to neurologic symptoms and sagittal plane malalignment. In general, patients who do not respond to nonoperative care have significant improvement in patient-reported outcome measures postoperatively.

Nevertheless, operations in these patients are associated with significant risk, as it is estimated that approximately 40 percent of patients will have a complication after surgery to correct adult spinal deformity.1 Risks include, but are not limited to, wound infection, urinary tract infection, medical complications, malpositioning and/or failure of instrumentation, nonunion, and proximal junctional kyphosis or failure.

Advertisement

In view of these risks, it is typically best that these large surgeries be performed at centers with high volumes of deformity cases and a multidisciplinary approach and protocol for the care of these patients. An in-depth understanding of adult spinal deformity, including age-appropriate alignment parameters/objectives, is critical for the preoperative planning and successful execution of surgical reconstruction. Intraoperative tools such as CT navigation and neuromonitoring, along with multidisciplinary preoperative assessment and the use of TXA and other blood management strategies, help minimize complications in these high-risk cases.

Dr. Savage (savagej2@ccf.org) and Dr. Orr (orrd@ccf.org) are spine surgeons in Cleveland Clinic’s Center for Spine Health and Department of Orthopaedic Surgery.

Advertisement

Advertisement

An argument for clarifying the nomenclature

An expert talks through the benefits, limits and unresolved questions of an evolving technology

Recommendations on identifying and managing neurodevelopmental and related challenges

Phase 2 trials investigate sitagliptin and methimazole as adjuvant therapies

Aim is for use with clinician oversight to make screening safer and more efficient

Rapid innovation is shaping the deep brain stimulation landscape

Study shows short-term behavioral training can yield objective and subjective gains

How we’re efficiently educating patients and care partners about treatment goals, logistics, risks and benefits