What is cancer immunotherapy teaching us?

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/78dc17a6-543a-4949-917b-e3976ed338f6/17-RHE-1216-Calabrese-Hero-Image-650x450pxl_jpg)

17-RHE-1216 Calabrese Hero Image 650x450pxl

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

It has been the dream of oncologists to develop a safe, targeted, host-sparing form of cancer immunotherapy since the nineteenth century, when Dr. William Coley pioneered one of the earliest iterations of cancer immunotherapy by injecting bacteria directly into tumors. Over the past 140 years, numerous attempts to refine cancer immunotherapy have led to a string of disappointments from simple lack of efficacy to dramatic toxicities.

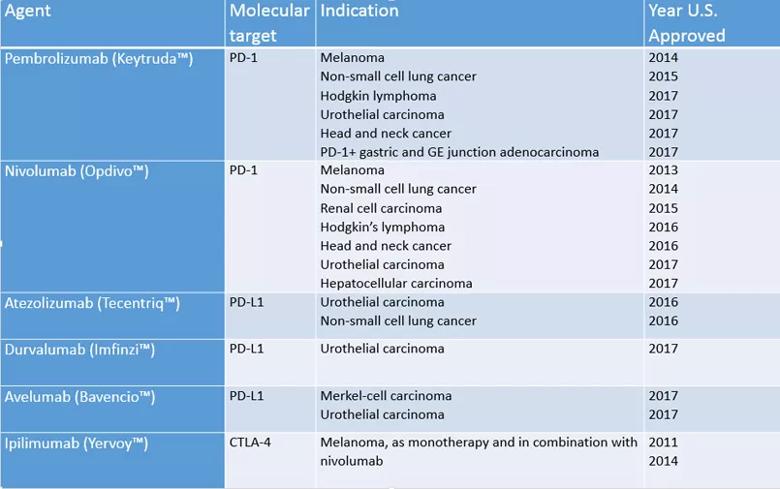

In 2011, the first of a new class of agents known as checkpoint inhibitors was approved for the treatment of advanced melanoma, beginning a new era in cancer immunotherapy. Following the approval of ipilimumab, five other monoclonal antibodies have been approved, and many more are in development. A quick scan of clinictrials.gov reveal over 1300 active clinical trials in the cancer immunotherapy arena.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/f52acd85-224e-42fe-9590-4829767b0ea1/17-RHE-1303-Calabrese-Inset-Table-01-805pxlwidth_jpg)

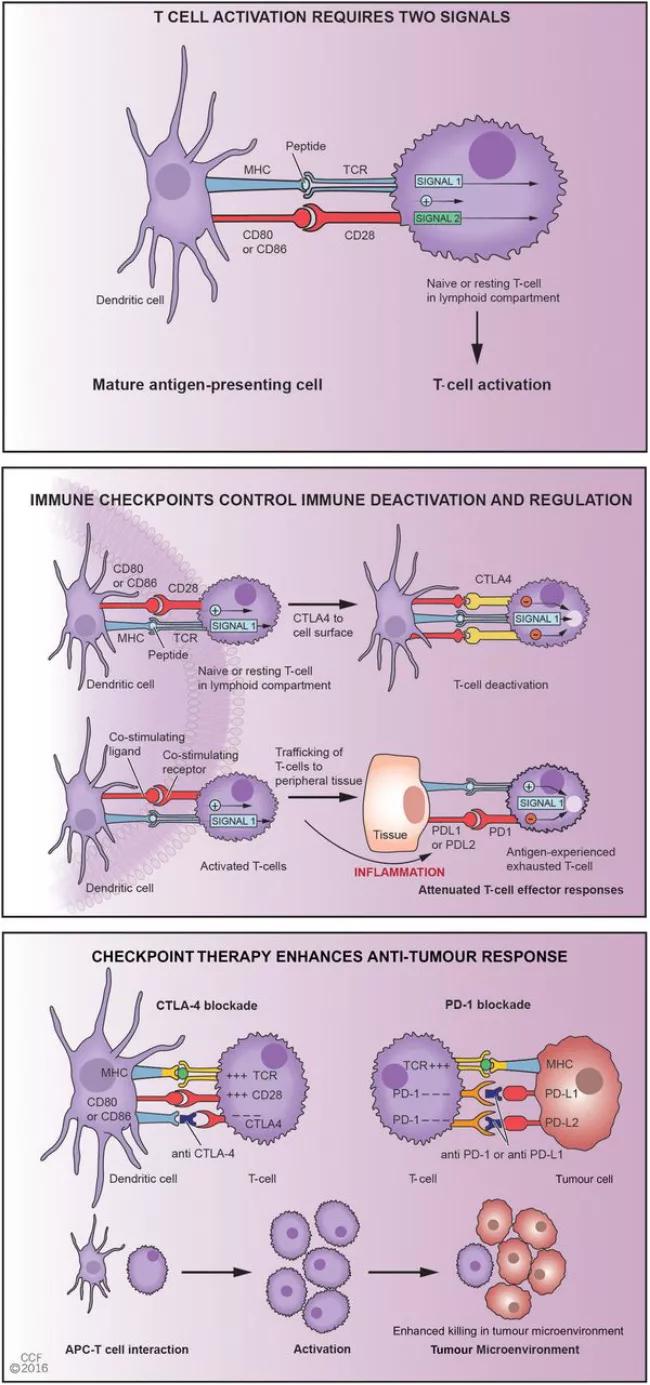

Checkpoint inhibitors derive their name from critical nodes of control located throughout the integrated immune system. Consider that a naïve T cell, once it encounters its cognate antigen (such as an infection or vaccine), can activate and proliferate several log phases and ultimately grow to over a million progeny in seven to 10 days. Implicit with such activation and proliferation is the capacity to down regulate, whereby a small number become memory cells and the majority die in programmed cell death pathways. These negative controls are often referred to as checkpoints and include CTLA4 (expressed on CD4 and CD8 cells, as well as PD1). While these molecules are the focus of current inhibitors, researchers are examining many other candidates including TIM-3, LAG-2, CD160, VISTA and others.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/9cceae73-2d33-4e61-9a8a-f22aca4cc2de/16-RHE-1747-Calabrese-Inset-Image-01_jpg)

T-cell activation is highly choreographed, requiring two signals for activation (i.e. TCR and Antigen & CD28 and CD80/86). Following activation, proliferation and differentiation check points such as CTLA4-CD80/86 and PD1-PDL1 or PDL2 intervene and brake the system. Figure republished with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Drugs targeting these checkpoints reinvigorate T cells in the tumors, leading to apoptosis and hopefully remission from advancing cancers. To date, these therapies have been highly effective in some tumors used both singly and in combination.

By now most rheumatologists as well as other specialists are aware that checkpoint inhibitors are capable of unleashing a wide array of autoimmune and autoinflammatory adverse events found virtually within every organ system. These complications have posed new challenges to all practitioners, and guidelines for the management of some but not all have been proposed.

Recent work has suggested that these same checkpoints may have a role to play in the pathogenesis of de novo autoimmunity as well. Work from the University of Cambridge has demonstrated that the same type of exhausted T cells that is bad for cancer may be good for autoimmunity, correlating with higher rates of remission and milder disease. It remains to be seen whether these important translational observations can be converted into therapy or biomarkers useful for patients with autoimmune diseases.

The pathogenesis of these immune-related adverse events or irAEs will be discussed at the 6th Annual Basic and Clinical Immunology for the Busy Clinician to be held March 9-10, 2018, in Miami Beach, Florida. This one-of-a-kind course features three distinct modules: Fundamentals of Basic and Clinical Immunology, Immune Therapeutics (Advances in Biology Therapies for IMIDs), and Immunologic Health. It will also include daily yoga and mindfulness meditation.

Advertisement

To view the full agenda and faculty and to register, visit www.ccfcme.org/clinical.

This activity has been approved for AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™.

Dr. Calabrese is Director of the R.J. Fasenmyer Center for Clinical Immunology.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Researching the biological basis for why treatment is or is not effective

Scribing system helps create more face-to-face interactions

A conversation with Leonard Calabrese, DO

The case for continued vigilance, counseling and antivirals

High fevers, diffuse rashes pointed to an unexpected diagnosis

No-cost learning and CME credit are part of this webcast series

Summit broadens understanding of new therapies and disease management

Program empowers users with PsA to take charge of their mental well being