State-of-the-art review gives guidance for populations not addressed in TAVR trials

As transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) expands in use as an alternative to surgical AVR (SAVR) for patients with severe symptomatic aortic valve stenosis across a wide spectrum of surgical risk, which patients are still best served by SAVR?

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

That question is at the center of a comprehensive State of the Art Review recently published in the European Heart Journal by an international team of expert cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons.

Their bottom-line guidance is that the many intersecting factors that influence the choice of TAVR versus SAVR preclude any single uniform treatment strategy but instead underscore the importance of decision-making by a multidisciplinary heart team that accounts for the individual patient’s clinical and anatomic factors and lifetime management considerations.

The review lays out the latest evidence across a range of factors relevant to the decision while also proposing several potential lifetime management strategies for patients.

“We devoted particular attention to patient populations that were not included in randomized clinical trials of TAVR,” observes interventional cardiologist Samir Kapadia, MD, a co-author of the review and Chair of Cardiovascular Medicine at Cleveland Clinic.

Across multiple randomized trials in patients at various levels of surgical risk, TAVR has repeatedly been shown to yield mortality and stroke outcomes comparable to or better than those with SAVR through the mid-term follow-up that is currently available. This outcomes profile, together with TAVR’s reduced invasiveness and shorter recovery time, has elevated transfemoral TAVR to a spot alongside SAVR in having a class I recommendation for patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis in the latest U.S. and European treatment guidelines.

Advertisement

At the same time, the evidence supporting TAVR was limited to carefully chosen patient populations, and uncertainties remain around the long-term durability of TAVR (as well as SAVR) prostheses and what constitutes ideal lifetime management for patients with severe aortic stenosis.

Many of the knowledge gaps around TAVR’s utility involve anatomic or clinical features not accounted for in initial clinical trials. Much of the review discusses these features in the context of anatomic risk stratification.

“When the aortic valve anatomy is favorable for TAVR and transfemoral access is possible, TAVR will result in clinical outcomes comparable to those of SAVR,” Dr. Kapadia explains. “In contrast, when patients have unfavorable anatomy in the TAVR implantation zone or poor femoral access, SAVR is the treatment of choice. But there is also a ‘gray zone’ of intermediate-risk situations that demand judicious, individualized decision-making, and that’s what we aimed to address.”

The review covers the following anatomic/clinical factors that generally favor SAVR, with detailed discussion of when and why SAVR may be indicated:

Advertisement

Additional discussion is devoted to the following, with these general recommendations:

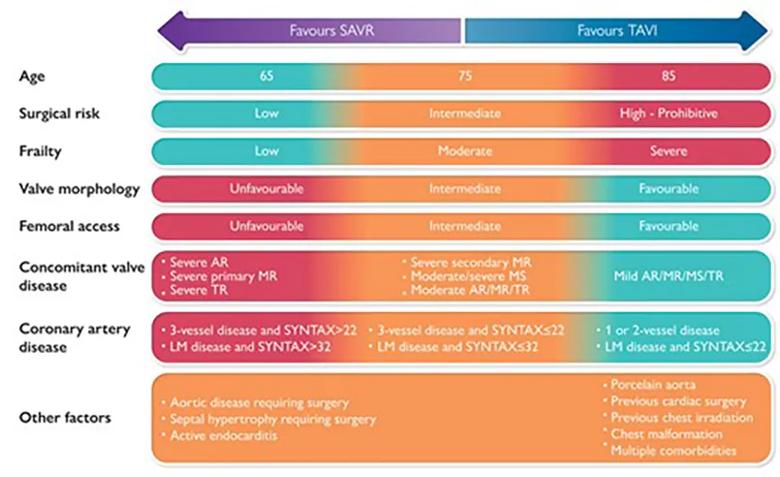

The figure below summarizes the contributions of many of these clinical and anatomic factors to decision-making between TAVR and SAVR.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/858aebc0-31d8-4ac6-a0e5-5cea249f77d6/22-HVI-2935765-CQD-inset_jpg)

Figure. Graphical abstract of the decision-making process when choosing between TAVR (TAVI) and SAVR. Reprinted with permission from Windecker et al., European Heart Journal (25 Apr 2022), doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac105. © The Authors 2022. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of European Society of Cardiology.

The review concludes with a detailed discussion of lifetime management, noting that this issue looms larger as TAVR use expands to younger and lower-risk patients with longer life expectancy. Direct evidence on this issue is limited, as comparative data between TAVR and SAVR are currently restricted to five to eight years.

Valve durability is central to lifetime management, and durability data for transcatheter valves are chiefly derived from patients treated at an advanced age — i.e., a mean of over 80 years. At the same time, data on the long-term durability of surgical bioprostheses are limited as well, prompting the authors to state that valve durability remains inconclusive in the decision-making context.

Other questions related to lifetime management that require continued longitudinal monitoring include the clinical relevance of:

Additionally, the need for lifelong anticoagulation in patients undergoing SAVR with a mechanical prosthesis is a key consideration, particularly for younger individuals. Noting that younger patients who undergo treatment with bioprostheses may require three or more interventions over their lifetime, the authors outline the pros and cons of various sequential intervention strategies for various patient types, such as TAVR-SAVR-TAVR or SAVR-TAVR-TAVR, depending on patients’ individual circumstances and values.

Advertisement

“The many considerations that factor into the initial decision between TAVR and SAVR — not to mention the need to plan for potential subsequent valve procedures down the road — explain the need for decision-making by a multidisciplinary heart team at a valve center of excellence to ensure the highest-level, most fully informed care for aortic stenosis,” says Dr. Kapadia. “At this point, this is one of the few certainties in decision-making around TAVR versus SAVR. Another certainty is that both SAVR and TAVR technologies and techniques will continue to improve, and that will further refine decision-making in the years ahead.”

“SAVR can be preferred when patient anatomy is suboptimal for TAVR,” says James Yun, MD, PhD, a Cleveland Clinic cardiothoracic surgeon who performs both procedures but wasn’t involved in the European Heart Journal review. He says leading examples include severe calcification of the left ventricular outflow tract, bulky eccentric leaflet calcification, excessive annular size and low-lying coronary ostia with small sinuses of Valsalva.

“Surgery also is preferred when low- and intermediate-risk patients present with a coincident second surgical indication, such as ascending aortic aneurysm, coronary artery disease or other valvular disease,” adds Dr. Yun. “Finally, in the lifetime management of aortic stenosis, SAVR is seriously considered in patients’ younger years to match procedural risk and advancing age appropriately.”

Advertisement

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic

Why and how Cleveland Clinic achieves repair in 99% of patients

Multimodal evaluations reveal more anatomic details to inform treatment