Large single-center series demonstrates safety and efficacy for extending procedure

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/d44767f5-7bbc-477a-b08c-2e6fbd24f727/systolic-anterior-motion-feature)

hypertrophied human heart

Midventricular and apical septal muscle can be resected successfully and safely with a transaortic approach by experienced surgeons aided by specialized instruments and detailed imaging, concludes a large new Cleveland Clinic study. This strategy for relieving obstruction and enlarging the left ventricular chamber is employed at Cleveland Clinic for patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) who are unresponsive to or intolerant of maximal medical therapy. The study was published online in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (Epub 2024 Apr 17) and presented at the recent 104th annual meeting of the American Association for Thoracic Surgery.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“In our experience, the transaortic approach can be used to reach the midventricular and apical regions, allowing extended myectomy to be conducted without ventriculotomy,” says the study’s senior and corresponding author, Nicholas Smedira, MD, MBA, a Cleveland Clinic cardiothoracic surgeon with a specialty interest in septal myectomy. “The transaortic approach is more comfortable than the transapical approach for most cardiothoracic surgeons, offers a more conventional anatomical viewpoint and provides easy access for mitral valve repair.”

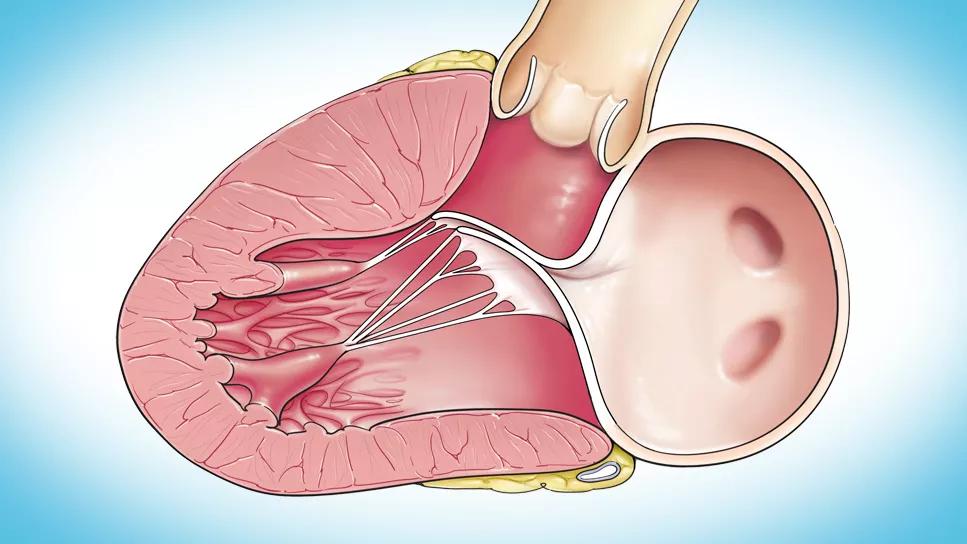

While myectomy for isolated basal septal hypertrophy is usually performed via a transaortic approach, transapical entry — requiring left ventriculotomy to access the septum — is usually recommended for midventricular and apical hypertrophy. Over the past several years, Dr. Smedira has used the transaortic approach to extend resection from the base as far as the apex (Figure), thereby avoiding the need for repeat myectomy due to inadequate resection.

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/49fa7088-b0a0-4442-86da-488ba9c32490/LV-LVOTO_systolic-anterior-motion_24-HVI-4921735)

Figure. The transaortic approach studied extends resection from the basal septum as far as the apex.

“Cleveland Clinic has been performing myectomies for over 40 years, during which time we have continually refined the operation,” Dr. Smedira notes. “This has included designing and developing instruments to facilitate the operation. It also includes collaborating with our cardiovascular imaging colleagues to gain a comprehensive understanding of septal anatomy and function, guide how much muscle to remove, and assess the efficacy of the procedure. This extension of the transaortic approach evolved from that ongoing process of refinement.”

Advertisement

The new retrospective study was undertaken to examine this strategy with regard to operative features, safety and efficacy.

From January 2018 to August 2023, transaortic septal myectomy was performed in 940 patients at Cleveland Clinic. Of these, 258 patients (27%) underwent isolated basal myectomy and were excluded from this analysis. The final cohort consisted of 682 patients who underwent myectomy of the midventricular and/or apical septum using the transaortic approach.

Anatomy varied among the patients, requiring different amounts and areas of muscle to be resected. Most patients had 5 to 15 grams of muscle removed (median, 10 g), with the largest resection weighing 32 grams.

The following combinations of septal areas were most commonly resected:

Small numbers of patients underwent either isolated midventricular, midventricular plus apical, or basal plus apical resections.

The median total cardiopulmonary bypass time was 41 minutes, and the median cross-clamp time was 32 minutes.

The primary endpoint was obstruction relief as assessed by intraventricular gradient. Mean intraventricular gradient improved from 102 ± 41 mmHg preoperatively to 16 ± 10 mmHg on intraoperative post-myectomy transesophageal echocardiography. Almost all patients (96%) achieved a gradient of 36 mmHg or less, the prespecified threshold for adequate myectomy.

Advertisement

Operative and postoperative complications included the following:

No aortic or mitral valve injuries occurred.

“The safety profile and the aortic cross-clamp times are similar to those reported for the transapical approach,” Dr. Smedira observes.

Among the cohort, 145 patients (21%) underwent successful concomitant mitral valve repairs, 137 of which were performed via the transaortic approach. Most mitral valve repairs were indicated primarily for HCM-related pathology (85%); 13% of cases involved intrinsic mitral valve disease, and 2.1% of cases involved both issues.

In addition, 16 patients (2.3%) had concomitant mitral valve replacement (15 with a bioprosthesis and one with a mechanical valve). Two were performed after failed attempts at mitral valve repair.

The authors note that elongated anterior leaflets should be resected or plicated at the time of myectomy. Further operative techniques have been described by these Cleveland Clinic authors in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2019;157[6]:2289-2299), Innovations (Philadelphia) (2023;18[1]:4-6) and Operative Techniques in Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery (2023;28[4]:272).

Advertisement

In general, Dr. Smedira emphasizes that the following are critical to surgical success in this context:

“More than 70% of patients in our study period who underwent septal myectomy for relief of obstruction required resection beyond the basal septum,” Dr. Smedira concludes. “Our overarching goal is the safe removal of the maximum amount of muscle to relieve obstruction and enlarge the left ventricular cavity if needed.”

“Surgical therapies are well established for relief of dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in the setting of basal septal hypertrophy and systolic anterior motion of the mitral valve in a symptomatic patient with obstructive HCM,” notes Milind Desai, MD, MBA, Director of Cleveland Clinic’s Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Center. “However, they are less established for mid- and distal cavity hypertrophy in other patients with symptomatic ‘nonobstructive’ HCM or in those with mid-cavitary obstruction.

“This study represents a step in the right direction using a conventional transaortic approach versus an apical myectomy, which requires a transapical approach and, in turn, a repair of the left ventricular apex,” he continues. “At the same time, this landscape is going to evolve in the next decade with the emergence of effective nonsurgical therapeutic options, including the new class of cardiac myosin inhibitors such as mavacamten.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

But improvements didn’t correlate closely with physician-assigned NYHA class, study finds

End-of-treatment VALOR-HCM analyses reassure on use in women, suggest disease-modifying potential

Cardiac imaging substudy is the latest paper originating from the VANISH trial

Vigilance for symptom emergence matters, a large 20-year analysis reveals

Phase 3 ODYSSEY-HCM trial of mavacamten leaves lingering questions about potential broader use

Our latest performance data in these areas plus HOCM and pericarditis

Tailored valve interventions prove effective for LVOTO without significant septal hypertrophy

5% of flagged ECGs in real-world study were from patients with previously undiagnosed HCM