New risk score pools factors that may predict adverse outcomes in the uncommon phenotype

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/85145304-9542-4eaa-8ee0-f893ced9be8f/hypertrophic-cardiomyopathy-feature)

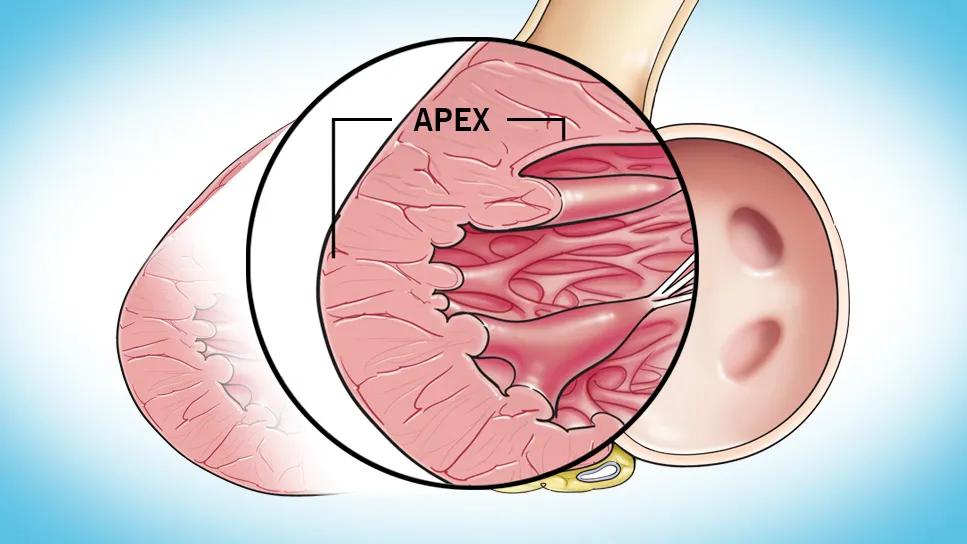

left ventricular apex in heart affected by hypertophic cardiomopathy

Cleveland Clinic researchers have identified five specific characteristics that distinguish patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (aHCM), a distinct but little-known variant of HCM. The results — from a registry-based study of one of the largest reported cohorts with aHCM in a non-Asian population — were published in JACC: Advances.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

“We felt it was important to identify specific characteristics in patients with apical HCM that impact their future outcome, given the known phenotypic differences between apical and obstructive HCM,” says senior and corresponding author Milind Desai, MD, MBA, Director of the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Center at Cleveland Clinic. “We also created an apical HCM risk score, which uses age, apical aneurysm, left atrial volume index, serum creatinine and right ventricular systolic pressure to help predict the likelihood of adverse events in this population.”

Apical HCM, which involves hypertrophy confined primarily to the left ventricular apex, is a relatively uncommon phenotype, reported in approximately one in four Asian patients with HCM and 10% or fewer non-Asian patients. Management can be challenging because the phenotype is not adequately addressed in major HCM guidelines and differs from that of the approximately 70% of HCM cases that involve dynamic left ventricular outflow tract obstruction.

Symptoms associated with aHCM are caused by diastolic dysfunction, abnormal lusitropy, microvascular angina and low stroke volume resulting from a small ventricular cavity. Recent reports have called into question long-held assumptions that aHCM is a more benign variant of HCM and that prevalence is low in non-Asian populations.

Data for the new research were from 462 patients diagnosed with aHCM at Cleveland Clinic between January 2001 and February 2021. Diagnosis was based on typical features, including apical wall thickness ≥15 mm and a ratio of maximal apical to posterior wall thickness ≥1.5, as assessed by experienced cardiologists using two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography and, in 53% of patients, cardiac magnetic resonance.

Advertisement

The cohort comprised 6.8% of the 6,785 patients in the institution’s HCM registry during the study period. The aHCM cohort had a mean age at diagnosis of 58 years and was 68% male and 70% white.

Goals of the analysis were to describe characteristics that distinguish aHCM and to use those factors to develop a risk score for patients with the condition. The primary endpoint was a composite of death, appropriate defibrillator discharge or need for cardiac transplantation over the duration of patients’ follow-up in the registry.

To identify variables potentially linked to the primary endpoint, the authors conducted univariable survival analysis, after which variables were assessed in a multivariable Cox regression model to determine which were predictive of survival.

At baseline, 67% of patients were asymptomatic and 69% had no risk factors for sudden death. Baseline imaging revealed the following cohort characteristics:

Over mean follow-up of 6.3 years, the primary composite endpoint occurred in 80 patients (17%), including death in 62 patients (13%). This translated to a composite event rate of 2.8% per year and a death rate of 2.1% per year. The authors note that these rates are higher than the rates of 1.3% and 1.1% per year, respectively, in an earlier report of Cleveland Clinic experience in patients with obstructive HCM (J Thorac Cardiovas Surg. 2018;156[2]:750-759.e3).

Advertisement

“The difference likely reflects a lack of proven treatments for apical HCM, whereas septal reduction therapies have been shown to provide excellent symptom relief and longer-term survival for obstructive HCM,” Dr. Desai notes. “It also suggests that apical HCM is not as benign as it was initially perceived to be.”

In the multivariable model, five variables were found to be statistically significantly predictive of the primary endpoint:

Using the five variables above, the authors developed an aHCM-specific risk prediction score with a range of 0 to 8 points. The factors with the highest individual scores were age >80 (3 points) and left atrial volume index ≥48 mL/m2 (2 points).

Applying the aHCM risk score to the study participants, the authors observed a graded increase in the rate of the composite primary endpoint that corresponded with increasing risk scores, as follows:

The aHCM-specific risk score showed good discrimination, with a C-statistic of 0.75, and good calibration, with an expected-to-observed ratio of 1.02 and a calibration slope of 0.91. The authors note that these associations were stronger than those of American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association risk factors and that there was no association between the European Society of Cardiology risk score and this study’s primary endpoint on univariable analysis.

Advertisement

The authors believe the risk score holds promise for improving prognostication for longer-term composite events in aHCM patients with no need for cumbersome computation, but they caution that their results require external validation.

“In the meantime,” Dr. Desai recommends, “clinicians should recognize that patients with apical HCM do not have a benign prognosis and should undergo diligent phenotypic characterization and risk stratification that goes beyond standard guideline-recommended stratification tools.”

“Once apical HCM is suspected,” adds co-investigator Nicholas Smedira, MD, MBA, Surgical Director of the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Center, “every effort should be made to identify the area with maximal wall thickness and apical aneurysm formation using multimodality imaging. Mounting evidence also suggests that debulking apical myectomy may be of benefit as an alternative to heart transplant in severely symptomatic apical HCM.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

End-of-treatment VALOR-HCM analyses reassure on use in women, suggest disease-modifying potential

Cardiac imaging substudy is the latest paper originating from the VANISH trial

Vigilance for symptom emergence matters, a large 20-year analysis reveals

Phase 3 ODYSSEY-HCM trial of mavacamten leaves lingering questions about potential broader use

5% of flagged ECGs in real-world study were from patients with previously undiagnosed HCM

High composite score in myectomy specimens signals worse prognosis

Few patients report left ventricular dysfunction or heart failure after one year

Avoidance of septal reduction therapy continues while LVEF dysfunction remains infrequent