Database analysis sets stage for a multicenter trial assessing TAVR’s potential role

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/a0b80cbd-17de-4c23-a6e1-b6e281c3604b/20-HVI-2018223_aortic-valve-anatomy_650x450_jpg)

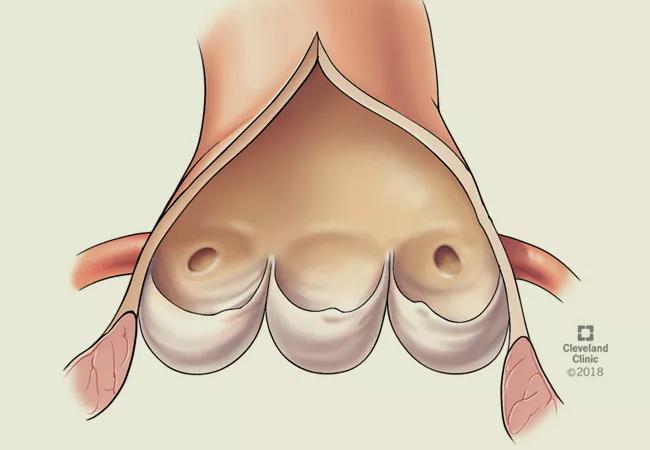

20-HVI-2018223_aortic-valve-anatomy_650x450

While use of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is growing among older adults with severe aortic stenosis at various levels of surgical risk, surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) has remained standard of care among patients aged 55 or younger. The latter group includes a growing population with congenital heart disease (CHD) who face multiple sternotomies for repeat operations over their lifetime.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

To better understand how suitable an option TAVR might be for these younger patients, Cleveland Clinic cardiac surgeons recently helped lead a national database analysis of AVR procedures and outcomes among young and middle-aged adults.

The analysis, published online in Annals of Thoracic Surgery, included adults aged 18 to 55 in either of two Society of Thoracic Surgeons databases — the Congenital Heart Surgery Database and the Adult Cardiac Surgery Database — who had undergone TAVR or SAVR from 2013 to 2018.

Of the 45,753 unique patients included, 16% had CHD. TAVR was performed in 1%; 97% received a mechanical or bioprosthetic valve; and the remaining 2% received an autograft, homograft or Ozaki valve. Notably, TAVR volumes increased by 167% from 2013 to 2018.

The analysis revealed that the stroke rate was lower with isolated SAVR compared with TAVR (0.9% vs. 2.4%, P = 0.002), as was 30-day mortality, although not to a statistically significant extent (1.6% vs. 2.9%; P = 0.076).

Key findings from multivariable analyses included the following:

The authors concluded that, given the “uniformly excellent” results with SAVR, particularly regarding stroke, the data favor SAVR in this population.

“We were a little surprised by how well SAVR performed,” says study co-author Tara Karamlou, MD, MSc, a Cleveland Clinic pediatric and congenital heart surgeon. “As a surgeon, it is heartening to recognize that surgical outcomes are excellent. However, TAVR has potential in this population and is being used with increasing frequency. We feel the need to start applying the technique in a thoughtful way.”

Advertisement

Important differences in underlying pathologies mean the results of TAVR in a low-risk older population cannot necessarily be applied to younger patients, Dr. Karamlou notes. “Most younger patients have aortic insufficiency, not necessarily aortic stenosis,” she says. “Also, they often have no calcification.”

Nevertheless, to date Cleveland Clinic has performed TAVR in approximately 30 younger patients (i.e., ≤ 60 years), some with adult CHD. “Outcomes have been excellent,” she says. “In general, we prefer SAVR, particularly due to stroke outcomes, but TAVR is an excellent option in certain situations.”

While early outcomes with TAVR are good, understanding the durability of TAVR valves in younger patients will be critical to establishing the procedure’s place.

“Will TAVR stand the test of time? How will it compare to SAVR in the long run?” asks Dr. Karamlou. “We must be wary of causing hypoattenuated leaflet thickening in younger patients, requiring them to need multiple valve replacements.”

While long-term disability is important, it’s not the only consideration, adds study co-author Hani Najm, MD, Chair of Pediatric and Congenital Heart Surgery at Cleveland Clinic. “The combination of percutaneous and operative options may decrease the need for frequent surgery in this population,” he says.

Dr. Karamlou cautions that TAVR should be performed only at centers with a robust surgical program for adult CHD. “You want to make sure you are not pushing patients toward TAVR,” she says. “The adult CHD population is different from a standard population, and these patients are very complicated.”

Advertisement

Moreover, the decision to proceed with TAVR must be made jointly with the patient. “Because TAVR in younger patients is an off-label use, patients need to know there are limitations in our ability to compare TAVR with SAVR,” she says.

The anatomy must be carefully vetted, since good peripheral access is necessary to deploy a TAVR valve. Stroke risk, which is higher with TAVR in younger patients, must be assessed. Then a suitable valve must be identified. “When we weigh these factors, surgical risk may outweigh TAVR risk, or vice versa,” she says.

The findings of this study helped clarify the advantages and limitations of SAVR and TAVR in a younger population and are being used to triage patients. “This analysis expanded our options for managing complex reoperative surgery for the aortic valve,” says Dr. Najm.

Notably, this study set the stage for a multicenter IDE safety and efficacy trial of TAVR in younger adults that involves devices from three different manufacturers and is slated to start in 2021. Dr. Najm says it will especially inform practice for adults with CHD.

Meanwhile, Cleveland Clinic is piloting virtual implantation software that will allow surgeons to choose and implant a valve based on a 3D reconstruction of a patient’s aortic root, aorta and coronary arteries.

“If this works out, it will further help us triage patients who will be good candidates for successful TAVR going forward,” says Dr. Karamlou.

Advertisement

Advertisement

A new CME opportunity in Chicago, May 15-16

After four decades, refinements to the gold standard of bypass continue as new insights emerge

Why definitive surgical closure is the gold standard, and new ways to make it possible

Modified-Bentall single-patch Konno enlargement (BeSPoKE) optimizes hemodynamics, facilitates future TAVR

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches