Resourceful approaches to the care of patients with microvascular disease and elevated Lp(a)

Seeking out expert care for coronary artery disease (CAD) often brings to mind referral for coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) in cases of challenging anatomy or when a minimally invasive approach is desired.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Yet an innovative, high-volume heart program like Cleveland Clinic’s can offer distinctive care options for patients at all stages of CAD, including long before they may need revascularization, and for patients with less-common forms of CAD.

This article, the second in a three-part series, shares a couple of examples, with a focus on the management of special patient populations — specifically, those with microvascular disease and elevated lipoprotein(a). Part 1 of the series focuses on noninvasive functional testing for obstructive CAD, and part 3 addresses refinements to revascularization care.

One traditionally overlooked subpopulation of CAD patients includes those with microvascular disease, or ischemia with non-obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA). Cleveland Clinic’s long-standing interest in INOCA grew in late 2020 when Khaled Ziada, MD, joined the Section of Interventional Cardiology, where he is one of three staff cardiologists with a specialty interest in the condition.

“We consider INOCA when patients present with angina but have little or no evidence of plaque in the coronary arteries,” Dr. Ziada explains. “Although it is quite common, there’s a significant need for better diagnosis, which is the foundation of proper management. Cleveland Clinic is one of just a few centers in the middle of the country with expertise in INOCA diagnosis and treatment.”

In the three years from 2021 through 2023, Cleveland Clinic conducted diagnostic testing for suspected INOCA in over 400 patients. Patients are evaluated via specialized catheterization lab testing for the two major forms of INOCA, microvascular angina and vasospastic angina, with most patients tested for both.

Advertisement

To assess for vasospastic disorders, Cleveland Clinic favors provocative testing with an intracoronary agent over the intravenous agents traditionally used. “We find intracoronary provocative agents to be more accurate and more diagnostic,” Dr. Ziada notes.

Typical assessment of microvascular function in the cath lab includes intracoronary injections of saline and use of adenosine to assess flow reserve. Cleveland Clinic cardiologists increasingly supplement standard microvascular function testing with a newer method, continuous thermodilution, that uses a microcatheter to infuse saline inside the coronary artery at different rates and without the need for adenosine.

Continuous thermodilution was pioneered in Europe; Cleveland Clinic was the first center to use it in the U.S. “Evidence indicates that it’s more accurate and reproducible than standard microvascular function testing,” Dr. Ziada says. “We’ve been using both the traditional measurements and continuous thermodilution to better understand the differences between them, but we are shifting to continuous thermodilution for all patients. We believe it will become the standard measurement used by everyone.”

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5ae0580c-0369-4d8c-a800-24a31a41ad30/coronary-microvascular-function-testing)

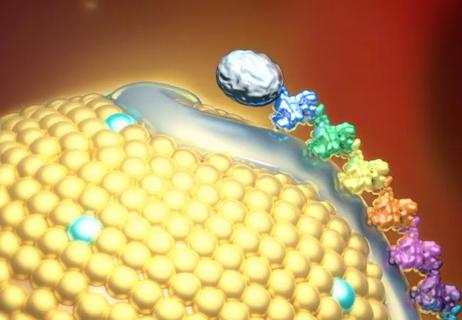

An example of the continuous thermodilution method for assessing microvascular function in a patient with INOCA. Absolute coronary flow and resistance are measured using continuous saline infusion at rest (left) and after inducing hyperemia (right). Both coronary flow reserve and microvascular resistance reserve are abnormal, indicating microvascular dysfunction.

Cleveland Clinic is also pioneering another promising diagnostic tool for microvascular disease — magnetocardiography. This noncontact, noninvasive test records magnetic fields produced by the heart’s electrical activity.

“Testing shows that magnetocardiography scans reveal abnormality in the magnetic fields in patients with microvascular dysfunction, even at rest,” Dr. Ziada says. “They appear to be about 70% to 80% accurate. We are working with the developer of the scanner to conduct validation studies that could support regulatory approval. Magnetocardiography is a simple, noninvasive scan that takes only about five minutes to do. If validation testing supports approval, this could be an appealing new screening option.”

Advertisement

Once patients are diagnosed with INOCA, they are offered contemporary therapy for the condition, which is aimed at alleviating angina symptoms and addressing long-term risk of cardiac events. Traditional anti-anginal medications are less effective in INOCA, so pharmacotherapy options for microvascular angina include beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, ranolazine and ivabradine, while those for vasospastic angina include calcium channel blockers and long-acting nitrates. These are often used against a backdrop of statin, aspirin and ACE inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker therapy. Management of risk factors (hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes) is emphasized, along with nutrition, exercise, weight management, smoking cessation and stress reduction.

“Most patients achieve significant improvement in symptoms and quality of life on contemporary therapy for INOCA,” Dr. Ziada says. “The improvement is dramatic in some and more measured in others. But there’s no question that we need better and more specific therapies for INOCA.”

To that end, Cleveland Clinic has begun exploring use of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin, which improves outcomes in heart failure with preserved ejection (HFpEF), in patients with microvascular dysfunction who have HFpEF. “About 75% of patients with HFpEF have microvascular dysfunction, and it’s believed that HFpEF is a form of microvascular dysfunction affecting the myocardium that leads to heart muscle stiffness and heart failure symptoms,” Dr. Ziada explains. “Based on those observations, we consider dapagliflozin in these patients and have seen relatively good success in terms of symptom relief and quality of life. We are now exploring a clinical study of SGLT2 inhibitors for microvascular dysfunction.”

Advertisement

Additionally, Cleveland Clinic offers selected patients with INOCA potential enrollment in the multicenter COSIRA-II randomized trial of an investigational coronary sinus reducing device for refractory angina. “While this study predominantly includes patients with nonrevascularizable obstructive CAD, there is an arm specifically for patients with microvascular dysfunction,” Dr. Ziada notes.

Finally, Cleveland Clinic is participating in the prospective multicenter DISCOVER INOCA registry that’s following patients for five years after INOCA diagnosis to better characterize outcomes. “Most outcomes data for INOCA are from the early 2000s,” Dr. Ziada says. “This registry should help us better understand outcomes and issues for contemporary INOCA patients.”

Once a week, Steven Nissen, MD, holds a clinic in which almost every patient has elevated levels of lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a). Most of the clinic’s patients have had multiple family members suffer a cardiac event and/or undergo revascularization by their forties or fifties.

“These patients typically say, ‘I just had my Lp(a) checked and it’s really high; I’m scared to death,’” says Dr. Nissen, Chief Academic Officer for Cleveland Clinic’s Heart, Vascular & Thoracic Institute. He adds that while there are no FDA-approved therapies for lowering Lp(a) levels, four promising investigational therapies are in clinical trials, and Cleveland Clinic is leading several of the trials.

“We are a focal point for much of the research into treating Lp(a)-related cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Nissen says, “and we are advocates for patients getting their Lp(a) levels checked. In addition to raising awareness of Lp(a) as an important risk factor, this identifies people at elevated risk of cardiovascular events. We can then treat all their other risk factors super aggressively and consider enrollment in a clinical trial of an investigational therapy if appropriate.”

Advertisement

Dr. Nissen and his colleagues have focused on Lp(a) because of the emergence of the investigational therapies and because the clinical impacts of Lp(a) elevation, once underappreciated, have grown increasingly apparent in recent years.

Those impacts manifest as a heightened risk — and often an accelerated course — of CAD-related events and conditions, particularly premature myocardial infarction, venous thromboembolism and calcific aortic stenosis. “Elevated Lp(a) can nearly double the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis,” observes Leslie Cho, MD, Co-Section Head of Preventive Cardiology, “and it tends to lead to disease at a younger age.”

Elevated Lp(a) is a genetically determined risk factor. Normal Lp(a) levels are less than 25 mg/dL. Significant risk of atherothrombotic events begins between 50 and 70 mg/dL and rises thereafter. Over 3 million Americans have levels of 180 mg/dL or greater, which confer extremely high risk.

Notably, Lp(a) levels are unaffected by available lipid-lowering therapies or by lifestyle interventions. “Elevated Lp(a) is one of the last untreatable frontiers of cardiovascular risk,” Dr. Nissen notes.

That may soon change, however, in view of the investigational therapies, known collectively as nucleic acid therapeutics. Eash of the two classes of these therapeutics — antisense oligonucleotides and short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) — act by degrading the messenger RNA that codes for apolipoprotein(a).

Four nucleic acid therapeutics — all given subcutaneously, from once monthly to once or twice a year — are now in clinical testing:

Because Lp(a) HORIZON, OCEAN(a) and ACCLAIM-Lp(a) are outcome trials, they should help determine whether significant Lp(a) lowering reduces major adverse cardiovascular events in people with Lp(a) elevation, as well as the magnitude of Lp(a) reduction needed to prevent events.

“We want clinicians to start assessing Lp(a) now so that when Lp(a)-targeted therapies become available, we’ll be ready to treat the patients who need them,” says Dr. Cho.

Advertisement

Novel approaches are available for patients at all stages of coronary artery disease

First-in-human phase 1 trial induced loss of function in gene that codes for ANGPTL3

A scannable recap of our latest data in these clinical areas

Proteins related to altered immune response are potential biomarkers of the rare AD variant

Yet 21.4% of tested individuals had Lp(a) elevation

Small interfering RNA lowered lipoprotein(a) by 94% during six-month follow-up after a single dose

In the wake of NOTION-3 findings, a strong argument for physician judgment remains

Phase 2 trial of zerlasiran yields first demonstration of longer effect with each dose of an siRNA