Intermittent statin dosing & bempedoic acid refresh the mix of options

Just when it seems like everything is settled about management of LDL cholesterol (LDL-C), new developments crop up. That’s been the case lately, prompting Consult QD to tap experts from Cleveland Clinic’s Department of Cardiovascular Medicine to survey two of the latest developments in LDL-C treatment: real-world strategies for statin intolerance, an anticipated new therapy that doesn’t cause muscle symptoms.

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Intermittent statin dosing for statin-intolerant patients isn’t new — Cleveland Clinic researchers published a study supporting this approach several years ago (Am Heart J. 2013;166:597-603) — but the practice has since gained traction and has become the cornerstone of an expanding suite of strategies to effectively care for statin-intolerant patients.

Important to that progress was the Cleveland Clinic-authored GAUSS-3 trial (JAMA. 2016;315:1580-1590), which used a randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled crossover design to provide the first robust evidence that muscle-related statin intolerance is a real and reproducible phenomenon. “This multicenter study showed that about 40% of patients with a history of muscle-related intolerance to at least two statins reported muscle symptoms while taking atorvastatin 20 mg/day but not while taking placebo,” says GAUSS-3 lead investigator Steven Nissen, MD, Chief Academic Officer of Cleveland Clinic’s Heart & Vascular Institute.

“GAUSS-3 was important because it demonstrated that muscle-related statin intolerance really does exist,” says Leslie Cho, MD.

History and exam are critical. As Co-Section Head of Preventive Cardiology, Dr. Cho has for years spearheaded Cleveland Clinic’s efforts to identify and care for patients with statin intolerance. Doing so, she notes, begins with a good history and physical exam. “To identify true statin intolerance, you need to really listen to your patients,” she says.

This involves asking them to describe their muscle symptoms — statin-induced aches can be severe and often affect large muscle groups. It is important to rule out substances that could be interfering with statin metabolism or elimination. These include alcohol, certain herbal supplements and medications such as diltiazem, amiodarone and some antibiotics and antifungals.

Advertisement

Once other causative substances are ruled out, patients who report muscle aches after trying two different statins are started on intermittent dosing of one of the hydrophilic statins — usually rosuvastatin, because of its long half-life, although pravastatin can be tried as well. “We use hydrophilic statins because they are less likely to get into muscle than the lipophilic statins,” Dr. Cho explains.

Specifics of the dosing approach. Intermittent dosing starts with a very low dose — typically 2.5 mg of rosuvastatin — once a week. Dosing is slowly escalated to 2.5 mg twice a week and then to 5 mg twice a week, with further increases in frequency as tolerated.

Cleveland Clinic has now used this approach in more than 3,000 patients, which Dr. Cho says is the world’s largest experience with intermittent statin dosing. This experience shows that about 70% of these patients end up being able to tolerate intermittent and/or low-dose statin therapy. “About 60% of patients can take a statin every day, after we start them on this slow process, and another 10% can take a statin three times a week,” Dr. Cho explains. “Only about 30% of patients who try intermittent dosing truly cannot take any statin therapy at all.”

Results can be surprisingly substantial. What kinds of LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) reductions can be achieved with this intermittent dosing approach? The 2013 American Heart Journal study mentioned above, which Dr. Cho led, achieved a mean LDL-C reduction of 21.3% with intermittent dosing, and she says results since then have been at least as good, with some patients achieving reductions of 25% to 30% with additive ezetimibe therapy.

Advertisement

Many patients and providers are amazed that as little as 5 mg of rosuvastatin a week can achieve any meaningful LDL-C reduction, but Dr. Cho points to the agent’s long half-life. And Dr. Nissen notes that early clinical trials of rosuvastatin showed LDL-C reductions of 30% with a dosage of just 1 mg/day. “There are real randomized controlled trial data that are supportive of this approach,” he observes.

“Of course, diet and exercise play a role too,” Dr. Cho adds. “In our prevention clinic, we always emphasize lifestyle factors in addition to medication, and for the 15% of the population who are high absorbers of dietary cholesterol from the small intestine, diet can make a tremendous difference.”

Additive and alternative therapies. Patients who continue with intermittent/low-dose statin therapy can be treated with any of several additive lipid-lowering medications, as needed, to help them achieve their goal LDL-C, such as ezetimibe, niacin and colesevelam.

For those who still don’t reach their goal, as well as for the 30% of participants who can’t tolerate any statin therapy whatsoever, PCSK9 inhibitor therapy is a good next option that achieves dramatic LDL-C reductions with a low risk of muscle-related adverse effects.

In these cases, the extensive initial trials of other, less-expensive, therapies as part of the intermittent-dosing approach often help overcome any insurance barriers to reimbursement. “At Cleveland Clinic we have a wonderful specialty pharmacy that helps with PCSK9 inhibitor requests, and the approval rate for our patients is upward of 90%,” says Dr. Cho.

Advertisement

She adds, however, that even if cost and insurance coverage are not a barrier to PCSK9 inhibitor therapy, there are occasional patients for whom anxiety over injections rules out PCSK9 inhibitors. That’s one reason Dr. Cho welcomes the prospect of likely FDA approval in early 2020 of a novel oral therapy for LDL-C reduction — bempedoic acid.

Regulatory filing for this agent, the first of the ATP citrate lyase inhibitor drug class to approach marketing approval, was submitted in February 2019. The heart of the application was data from the 2,230-patient CLEAR Harmony trial published last March (N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1022-1032), which showed that bempedoic acid significantly reduced LDL-C levels over 52 weeks relative to placebo when added to maximally tolerated statin therapy in people with atherosclerosis and/or heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Adverse effects were similar to those with placebo.

While approval is being sought solely on the basis of LDL-C reduction, bempedoic acid’s effect on clinical outcomes is being assessed as the focus of the ongoing CLEAR Outcomes trial (NCT02993406) of 14,000 patients with statin intolerance. Results from that multicenter study, which is being led by Cleveland Clinic with Dr. Nissen as the study chairman, are expected in 2022.

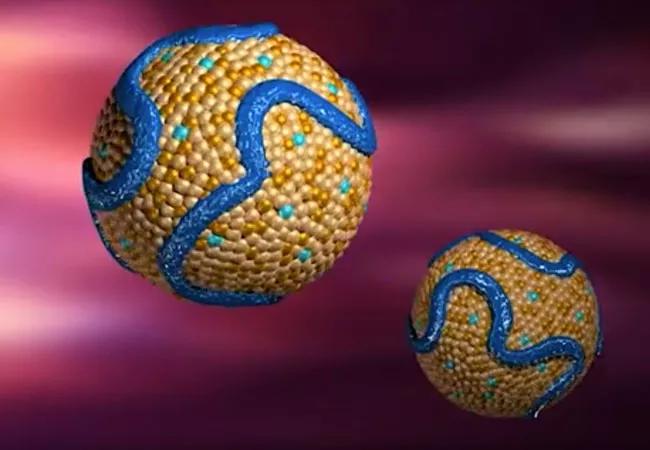

“Bempedoic acid is interesting because it acts on ATP citrate lyase, an enzyme that sits upstream of HMG-CoA reductase, which is the enzyme that statins act upon,” Dr. Nissen says. “But bempedoic acid has to be transformed in the liver to be active, and it is not active in muscle, so it can’t cause myalgias.”

Advertisement

LDL-C reductions with bempedoic acid are more modest than with statins; for instance, levels were reduced by a mean of 18% relative to placebo in CLEAR Harmony among patients already on maximal statin therapy. However, LDL-C reductions are somewhat greater in patients who don’t tolerate statins — typically about 25%, Dr. Nissen says. A recent phase 3 trial (Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019 Jul 29) showed a 38% mean reduction relative to placebo when bempedoic acid was combined with ezetimibe in patients on background statin therapy.

Dr. Nissen expects bempedoic acid to be approved for marketing alone and in combination with ezetemibe in early 2020. And because it can be given with low doses of statin therapy as well, he believes a triple-therapy regimen consisting of bempedoic acid, ezetimibe and a very low statin dose —perhaps 5 mg/week of rosuvastatin — may play an important role in the future treatment of statin-intolerant patients.

“Such a combination could produce LDL-C reductions of 50%, which is in the range of PCSK9 inhibitors,” he says. “It will be interesting to see how bempedoic acid ultimately fits best into practice.”

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic’s new dedicated program offers nuanced care for a newly recognized cardiovascular risk factor

Scenarios where experience-based management nuance can matter most

Introducing Krishna Aragam, MD, head of new integrated clinical and research programs in cardiovascular genomics

How Cleveland Clinic is using and testing TMVR systems and approaches

NIH-funded comparative trial will complete enrollment soon

How Cleveland Clinic is helping shape the evolution of M-TEER for secondary and primary MR

Optimal management requires an experienced center

Safety and efficacy are comparable to open repair across 2,600+ cases at Cleveland Clinic