Causes are multifactorial, but good surgical decision-making and technique reduce failures

Advertisement

Cleveland Clinic is a non-profit academic medical center. Advertising on our site helps support our mission. We do not endorse non-Cleveland Clinic products or services. Policy

Hallux valgus is a common forefoot ailment that frequently requires surgical intervention when nonsurgical management fails to provide symptomatic relief. Unfortunately, bunion surgeries can fail in a number of ways, often leaving the patient with more pain, persistent deformity and significant dissatisfaction and dysfunction. The question is, “Why do bunion surgeries fail?”

The cause of recurrent hallux valgus is usually multifactorial and includes patient-related and surgical factors. Patient-related factors include medical comorbidities such as obesity and osteopenia, as well as noncompliance with postsurgical weight-bearing restrictions. Skeletal immaturity, generalized ligamentous laxity, neuromuscular conditions, smoking and continued use of poor fitting shoes also can contribute to failure.

While patient-related factors individually and collectively increase the risk for complications, the majority of failed bunion surgeries result from surgeon error — either technical or in surgical decision-making.

Essentially, bunion surgeries can fail in the following circumstances, each discussed below:

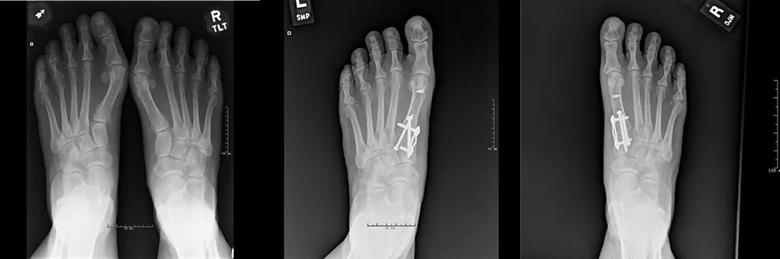

Surgeons select the appropriate procedure preoperatively based on clinical and radiographic evaluations of the individual deformity. By choosing an underpowered procedure, a surgeon may not be able to fully correct the deformity, leading to recurrence of the hallux valgus. For instance, internal fixation methods have expanded the range of deformities distal procedures can address. Yet, in general it is still well accepted that larger deformities with elevated intermetatarsal angles (IMA) are best treated with proximal procedures. Failure to correct the IMA to less than 10 degrees is a significant risk for undercorrection and /or recurrence of deformity (Figures 1A-C).

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/026c24c0-fb8e-49ee-a829-560bc426e89b/17-ORT-1246-Berkowitz-Inset-Images-No-01-8850pxl-width_jpg)

Figures 1A-C. Radiographs of 68-year-old female one year after bilateral bunion surgeries with residual deformity. Note the persistently elevated IMA. Each foot was subsequently revised using the Lapidus procedure.

A less obvious cause of undercorrection and recurrence is failure to appreciate and correct an elevated distal metatarsal articular angle (DMAA). This angle indicates how laterally the first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTPJ) is oriented. Ultimately, the final hallux valgus angle after bunion surgery will approximate the DMAA. Thus, if it is not corrected to less than 10 degrees, significant residual deformity or recurrence will occur. Choosing an osteotomy that specifically addresses and diminishes the DMAA provides the best opportunity for adequate and durable correction (Figure 2A-B).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/5b13f393-d76f-4306-84ea-e55d44484345/17-ORT-1246-Berkowitz-Inset-Images-No-02_650pxl-width_jpg)

Figures 2A-B. Radiographs of 60-year-old female who experience gradual recurrence of left bunion even after aggressive correction of IMA with Lapidus procedure. Note the elevated DMAA. When the right foot was surgically treated, both IMA and DMAA were corrected using a double osteotomy, resulting in excellent and durable correction of deformity.

Overcorrection of hallux valgus deformities is less common that undercorrection, but arguably results in greater symptoms and dissatisfaction. Whereas undercorrection often is the result of faulty surgical decision-making, overcorrection generally results from surgeon technical error.

Technical errors include a too aggressive lateral soft-tissue release or an overly aggressive resection of the medial eminence. Similarly, if the intermetatarsal angle is overcorrected, a hallux varus deformity may gradually develop (Figure 3). Many cases of postoperative hallux varus are symptomatic enough to require revision surgery, which can take the form of first MTPJ fusion or reconstruction.

Advertisement

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/815538fe-3638-4ea2-b2f0-361e14a5696e/17-ORT-1246-Berkowitz-Inset-Image-No_-03-650x450pxl_jpg)

Figure 3. Radiograph of 58-year-old female demonstrates hallux varus after overcorrection of the IMA.

First metatarsal osteotomies can be challenging to fix adequately due to the relative small size of the bone and limited area available for fixation. If osteopenia is present, the patient is noncompliant with weight-bearing restriction, or technical errors are made in creating or fixing the osteotomy, nonunion and/or malunion can develop. Nonunion of first metatarsal osteotomies produces pain at the nonunion site. Nonunion is also associated with dorsiflexion malposition, which transfers stress to the lesser metatarsals, resulting in transfer metatarsalgia. Transfer metatatarsalgia also can occur if the osteotomy heals in a dorsiflexed position.

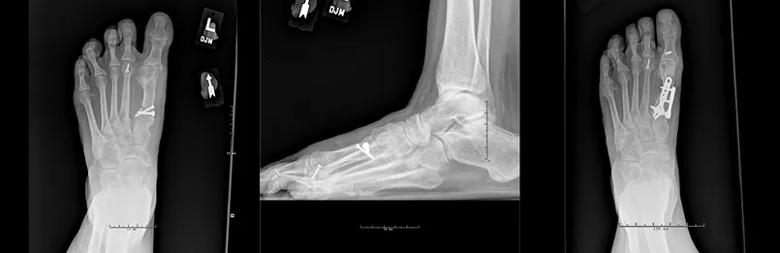

Nonunions and malunions of osteotomies used for bunion correction are almost always symptomatic and require revision with repeat osteotomy, bone grafting and revision fixation (Figures 4A-B).

Image content: This image is available to view online.

View image online (https://assets.clevelandclinic.org/transform/4ec90745-9361-4e7a-884d-5d532c57d0c3/17-ORT-1246-Berkowitz-Inset-Images-No-04-Correct850pxl-width_jpg)

Figures 4A-C. Radiographs of 57-year-old female with hallux varus and dorsiflexed malunion of a proximal first metatarsal osteotomy. Successful revision was achieved with first MTPJ reconstruction, correction of the malalignment, bone grafting and aggressive internal fixation.

Bunion surgery remains a technically challenging procedure, and patients have high expectations in terms of deformity correction and functional outcome. Undercorrection, overcorrection, nonunion and malunion remain the most common causes of failed bunion surgery. Although patient factors definitely contribute to disappointing outcomes, most failures are the result of poor surgical decisions and/or poor surgical technique.

Advertisement

Diligent preoperative evaluation and surgical planning combined with meticulous surgical technique will minimize these complications and provide patients with the outcome they desire.

Advertisement

Advertisement

How it’s similar but different from the direct anterior approach

Collaboration must cross borders and disciplines

Systematic review of MOON cohorts demonstrates a need for sex-specific rehab protocols

Should surgeons forgo posterior and lateral approaches?

How chiropractors can reduce unnecessary imaging, lower costs and ease the burden on primary care clinicians

Why shifting away from delayed repairs in high-risk athletes could prevent long-term instability and improve outcomes

Multidisciplinary care can make arthroplasty a safe option even for patients with low ejection fraction

Percutaneous stabilization can increase mobility without disrupting cancer treatment